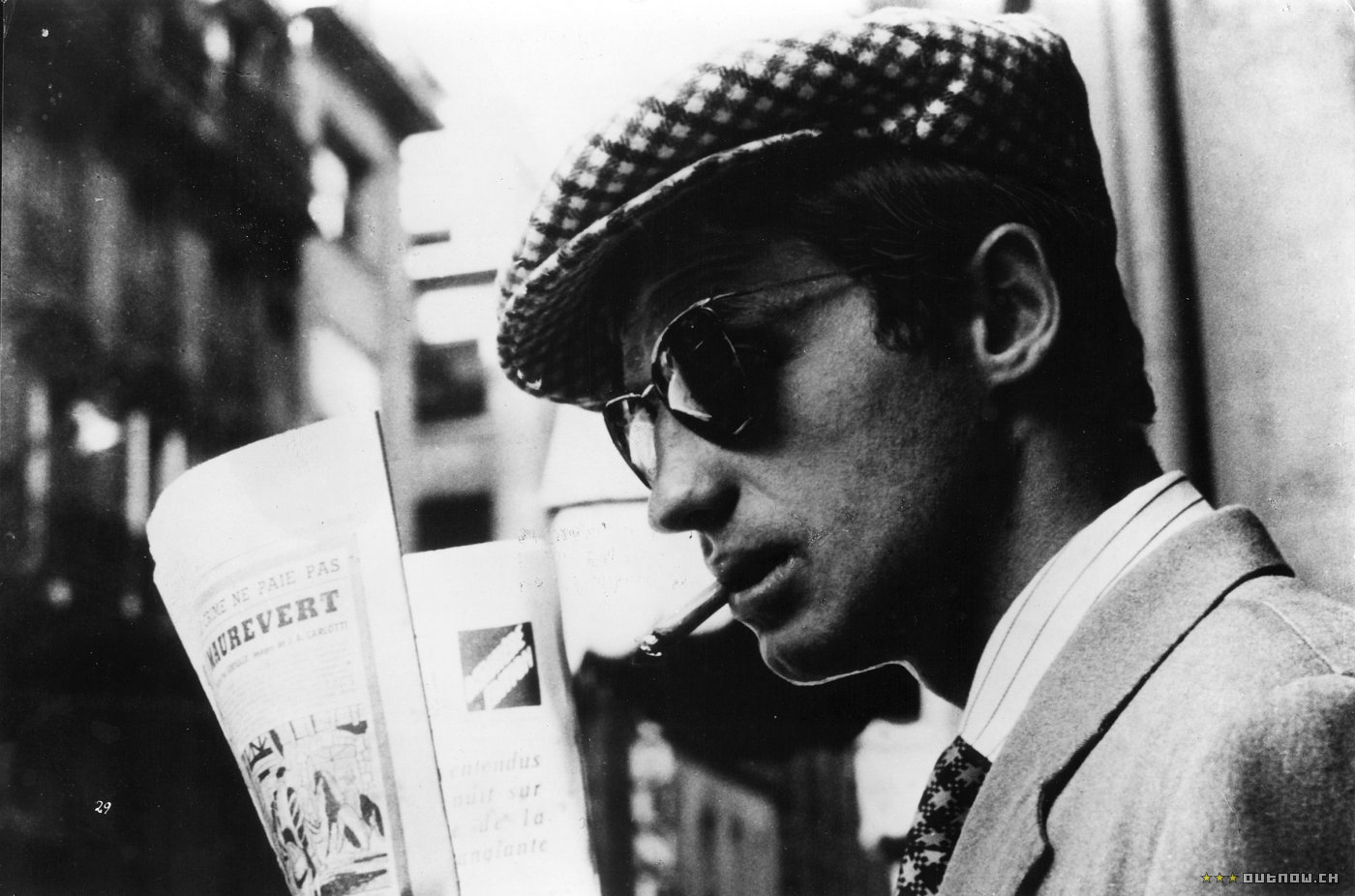

5. Breathless (1960, Jean-Luc Godard)

“Breathless can leave you breathless”. Satyajit Ray, possibly the most influential auteur in India, reflects on Godard’s piece de resistance in his book ‘Deep Focus’. His rather adulatory opinion of Godard’s masterful work is one that has a universal resonance. Set in Paris, the film follows a thief on the run, who murders a cop and takes shelter with his girlfriend, through a journey of self-discovery and high-voltage drama that will keep you hooked.

The most attractive and groundbreaking aspect of Breathless is its tight knitted editing, which lends a unique tenor to its visual appeal. Through the use of unconventional jump cuts and fast paced narration, Godard risks admiration and embraces criticism for his outwardly pretentious style, which even he knows to be true.

The way Godard constructs conversations between his characters also points to a change in perception, the connection between body and mind, theatre and spectacle, in stark contrast to the modern way, with someone like Noah Baumbach, who best embodies the more natural image of dialogue.

Godard stamps his authority as the free spirit of the New Wave, with this vibrant, seductive, and endlessly entertaining work of artistry that will forever adorn and expand the canvas of cinema.

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

Kubrick was that rare once in a lifetime occurrence that concretely changes the course of the craft. His ingenious vision and absolute dedication to art make him a cherished commodity. Every era, irrespective of the political or social context, has a watershed moment that defines it for the future generations. For science fiction in the ‘60s, it was Kubrick’s 2001.

The epic cinematic achievement changed the perception of many towards film and life beyond the earth, inspiring iconic future auteurs like Spielberg and JJ Abrams in the process. Audiences across the globes relished the opportunity to be transported into a fantasy-like world where they break free from earthly chains of imagination, getting to see stories other than ones about love, heartbreak, and virtuous families. In his many ground breaking films, Kubrick brought indelible changes in perception of the audience, the way they viewed film, and revolutionized their thinking process.

Right from the majestic opening shot, to the revolving set and Bowman’s space jog, Kubrick put things on screen no one dared to imagine. The film also won him his only Oscar for special effects. Apart from being probably the most influential film ever, 2001 changed people’s minds about the science fiction genre, which was relatively an overlooked one up until that point.

It opened doors for people in the industry to experiment and innovate and sculpt the present audacity of special effects, as we know today. The twisted narrative has an outpour of mesmerizing moments, all well worthy of remembrance and envy. One of the most iconic scenes in the movie sees HAL, the sentinel computer, be a passive audience to a conversation between two beings who supposedly control it.

Kubrick’s trademark visual style and meticulously assembled single-shots facilitate the story of dawn of man and the inevitable infatuation with a strange monolith in the most breathtaking of fashions.

Not only does Kubrick triumph with his craft and vision, but also manages great scientific accuracy in his portrayal of life in outer space. The rotating sets, high-yield special effects, and unsettling, high-brow symphonies all culminate to make 2001 a cathartic experience. Or like Warner Bros. describe the movie, “One movie that changed all movies. Forever”.

3. Mulholland Dr. (2001, David Lynch)

David Lynch has been labeled as many things. Pauline Kael called him “the first popular Surrealist” after Twin Peaks released; The Guardian went on and deemed him as “the most important director of his time”; and as his fans like to call him, “crazy”. Lynch’s career has been marked by a strong sense of detachment from conventional cinematic tropes and popular narrative choices.

His brand of cinema often takes shape in the form of absurdist, almost dream-like imagery with a disturbed protagonist, becoming his vessel to transport the viewer into another world. Mulholland Drive treads along similar lines.

In possibly one of the most complex storylines ever put on celluloid, Lynch creates realities within realities to narrate a horror-filled story of betrayal, poisonous ambition, and a slow-burning mystery that never comes to its resolution.

Betty Elms, possibly Lynch’s ode to yesteryear-Hollywood thespians, arrives in Los Angeles looking for work. As she settles in her aunt’s house, she comes across an intruder, a dark-haired amnesic woman, who introduces herself as Rita.

Showing no signs of memory of how she got in the house, Rita is comforted by Betty. What follows next is hard to keep track of and seemingly impossible to make sense of, with the only two constants in the story being Betty and Rita.

Much has already been said about how Lynch subverts commonplace wisdom and narrative structures to produce something unprecedented and original in Mulholland Dr. But the role of the actors has largely been overlooked.

Lynch, despite his histrionic style, places immense responsibility on the actors to provide the viewer with some accessibility to what he intends to create. Their deceptive brilliance sucks you in and entraps you in a cinematic warp that is difficult to escape.

Mulholland Dr. is a rare achievement in filmmaking and storytelling that sets new benchmarks for contemporary auteurs.

2. Dogville (2003, Lars von Trier)

Grace scampers from trailing mobsters. She looks for shelter in places that present themselves as compromises. With greed fueling the hosts’ actions over compassion and humanity, Graces’ life hangs in the balance.

There’s a piercing truth about the ugly side of humanity in Lars von Trier’s megalomaniacal attempt to take over every aspect of film production. As he gives true meaning to the phrase, “shooting on set”, Trier unearths a hard-hitting truth of life: goodness is a delusion. Nicole Kidman’s performance as Grace is absorbing and provides Dogville with a threshold of conventional thespian-esque semblance

. Every breath she draws inhabiting her character strikes emotions of fear and empathy.The ending is shocking and changes the entire perception of her character. Nicole Kidman gives a layered and humane performance that will have you rooting for her throughout the film. It is one of the best performances of the century.

Lars von Trier explores human nature with Dogville so brilliantly and the rage basically seeps from the films edges. The stage-like set might seem a little jarring at first but after a while, it grows on you, with a rather horrifying realization.

Trier’s subtlety in his craft allows his work criticism from almost every spectrum of the academic world. Dogville opened to polarized reviews, especially to hostile reception from American media alleging the film to be anti-American. Not just “I had a bad experience in America once” or the more typical “The US government is (negative remark)” but rather Trier despises the very foundation of American fundamentals, shall we say its farm-house philosophy, and its antiquated unspoken law.

Trier, however, doesn’t endorse a propoganda despite its themes being revolting in nature. Dogville is minimalist in the simplest form on the surface, but not facile in the slightest. Relating to themes of an (if fellow Kubrick aficionados would pardon a different use of the phrase) “eyes wide shut” mentality towards the events which take place in Dogville; the non-existent walls serving as a constant reminder to the false pretense of the “moral high ground” they claim; the main street’s name itself, “Elm Street” except there are no elms.

The Town is skeletal, the base (and concrete) elements of what is needed thematically. Much like the gangsters. The purely symbolic nature of the film comes as a pleasant surprise, given that Von Trier stems from the Bergman school of theory. It isn’t that much of a stretch though, as Bergman dabbled in symbols throughout his work.

1. Last Year At Marienbad (1961, Alain Resnais)

Alain Resnais is probably one of the most underappreciated geniuses and pioneers of the French New Wave. With an equally impressive filmography as his celebrated peers like Godard and Bresson, Resnais stands distinguished in memory through his perverted take on the shared world of film and life. Be it an illusionary film like Muriel that keeps you guessing until the very end, or a hard-hitting and gritty documentary about the horrors of the Holocaust, Resnais experimented with his style and substance, never repeating the same thematic structure.

His magnum opus, though, has to be Last Year at Marienbad, a truly hypnotic, dizziness-inducing delusion, whose original mystique remains intact even today. The challenge, as we discover during the course of movie, is not to understand the transpiring events, but to feel their emotions.

The story moves through a series of repetitive and confusing shots, often taking us with the protagonists in the same places at different times. Resnais indicates an exploration of human memory through his style about grief, and moments that rather find place in conscience because of their emotional vulnerability.

‘Unconventional’ might over-simplify what Resnais achieves with Last Year At Marienbad. The brilliance and the oddity of his narrative style second the understated humanism of the outstanding cast, who breathe life into the characters. Almost like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Resnais creates a memory maze that entraps his protagonists, whose attempts to get out prove futile.