5. Innocence Unprotected (1968) – Dusan Makavejev

Three years before his cult WR: Mysteries of the Organism, Makavejev’s status as one of the most powerful and controversial figures of the black Yugoslav wave was on show in his decision to take up the task of reworking the first sound film from Serbia. A film shot in 1941 during the Nazi regime -censored by both the Nazis and the Yugoslav authorities -by acrobat and escape artist Dragoljub Aleksic, where he tracks and amplifies his own great escapades.

Makavejev adds new footage (interviews with cast members and footage from the era of Nazi occupation) emerging with what he dubbed as a “montage of attractions”. This is a capsule of Makavejev’s keen eye for constructing works of art which operate deep within the discursive practices of dominant narratives, while disturbing their unity and animating their contradictions.

4. La Ricotta (1963) – Pier Paolo Pasolini

Part of the omnibus film Ro.Go.Pa.G, La Ricotta erects itself as one of Pasolini’s most penetrating analysis of late capitalism and the struggles of the excluded. Pasolini uses the background of the production of a blockbuster on the life of Jesus, the director captivatingly portrayed by Orson Welles, to work on his most fertile terrain: the investigation of the political subjectivity of emancipatory projects.

The political and philosophical register is patently Pasolinian, his heterodoxy is on full flow here, as always, remaining at the crossroads between mysticism and political antagonism, between Christianity and Marxism. La ricotta focuses its centrifugal force around Stracci, a poor local who is cast as an extra and henceforth totally overlooked and starved, to deliver a devastating critique of the petty-bourgeois obsession with representation.

3. Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven (1975) – Rainer Werner Fassbinder

After her husband kills his boss and himself, mother Kusters is left all alone to deal with the suffocating sensationalism of mass media, and a longing and inability to give a political expression to her struggles. She seeks shelter through oscillating between members of different political groups, each of them failing to address her most pressing need: that of opposing a fabricated account of her husband’s character, published in the media by a spineless journalist.

After his early engagement with arthouse films, Fassbinder in the early 70s became fascinated with the power of melodrama, especially that of Douglas Sirk. What informs this endeavor of Fassbinder, is that of using a fusion of melodrama and political cinema, to reflect on the conditions which make alienation possible. Where melodrama posits alienation as the metaphysical fate of man, political cinema injects a political and economic register of thought. Fassbinder is at his best in this ground, investigating and historicizing the place where politics can be thought in post-war Germany.

The film’s place in this list is secured by virtue of it being Fassbinder’s most sophisticated attempt at merging these two different forms together.

2. Letter to Jane (1972) – Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin/Groupe Dziga Vertov

After messing around with more traditional filmmaking in the 60s, Godard would turn his attention to the political potential of cinema (influenced by the work of Bertolt Brecht and the rising Maoist groups of the time), henceforth giving a new meaning to agit-props. Letter to Jane is the last collaboration between Godard and Gorin under the aegis of the Dziga Vertov group, which without a doubt marks Godard’s most ambitious and profound cinematic project. Jane Fonda starred alongside Yves Montand in Tout Va Bien, before being involved in numerous controversies regarding her relation to the Vietnam War.

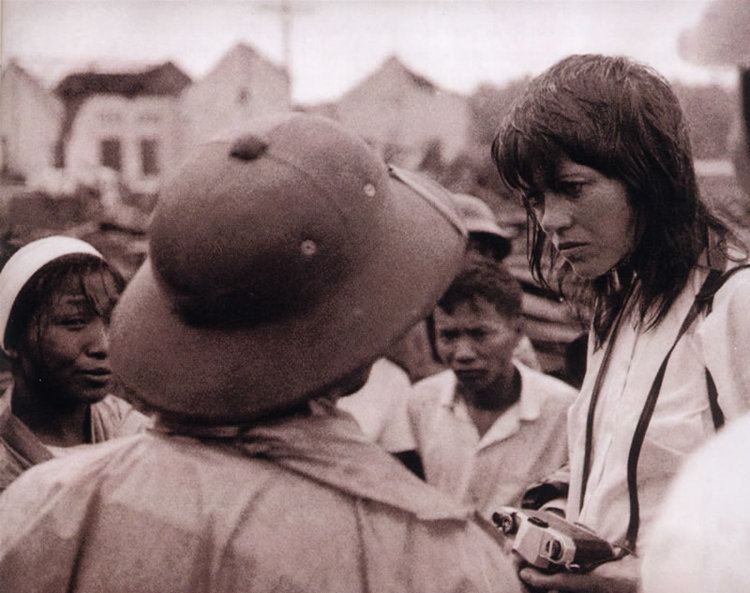

In Letter to Jane, the Dziga Vertov Group set out to produce a detailed analysis of new, refined forms colonialism has developed, through the investigation of a notorious news photograph of Jane Fonda engaged in a conversation with Vietnamese anti-colonialists in Hanoi. The photo in question, circulated widely at the time, and showed Fonda’s concerned face as central, while the Vietnamese involved in their struggle were shown as collateral.

In 52 minutes Godard and Gorin’s voiceover scrutinizes the still, emphasizing Fonda’s “western gaze” and the very anatomical arrangement of the photo, the primacy of Jane Fonda in the composition, as yet another instance where western guilt overshadows the political subjectivation of the colonized and oppressed.

1. Wind from the East (1970) – Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin/Groupe Dziga Vertov

Another product of the fruitful Dziga Vertov Group, starring Elio Petri’s regular Gian Maria Volonte and Anne Wiazemsky, this absorbing parody of westerns challenges the understanding of cinema as entertainment and re-invents the sound-image displacement and overlapping. Breaking the 4th wall is an alien notion to use when talking about their practice.

This is so because, the very place from where they speak, is overdetermined by the conjunctural self-referentiality of the text. Godard and Gorin speak from the ruins of the 4th wall and set the foundations of what we can call a very important exercise towards a materialist epistemology of the production of a militant film. This film sets out to ask fundamental questions for any serious practice of cinema: How does cinema register ideology? How are events in theoretical and political practice registered in cinema? How does cinema read ideology?

Through undertaking a restless critique of representation on the aftermath of May 68, Wind from the East displays an unrivalled awareness of the theoretical and political conjuncture of the time. Today, when the word contemporary work of art has been totally disinvested of meaning, Wind from the East is an indispensable reference point for all those works which long to be contemporaneous with their own time. Wind from East is to militant cinema, what Malevich’s Black Square is to painting.