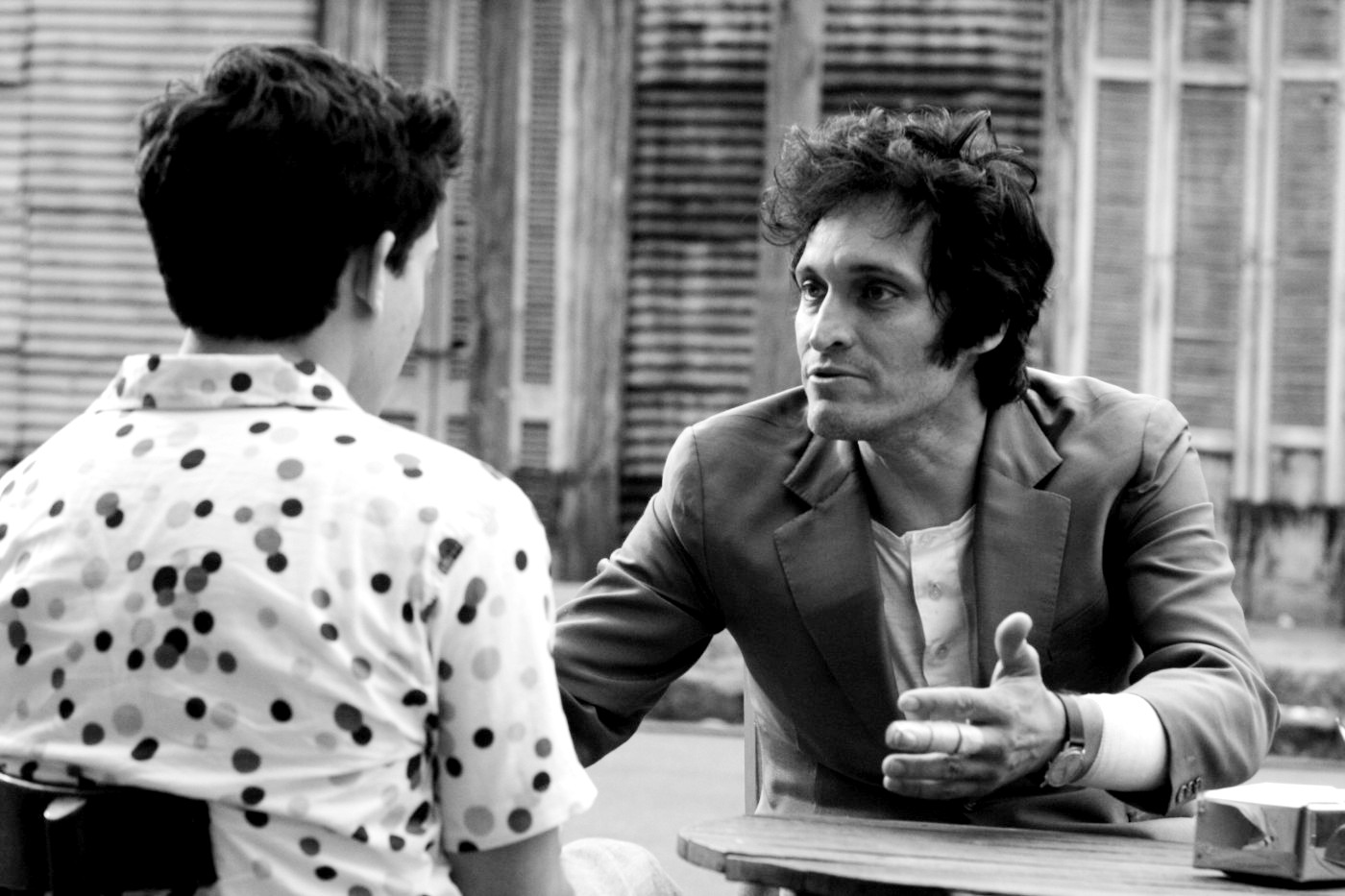

6. Tetro (Francis Ford Coppola, 2009)

After returning from a prolonged absence after the failure that was Jack, Hollywood New Wave pioneer Francis Ford Coppola finally returned in 2007 with Youth Without Youth and made it clear that during his absence he had re-thought many of his ideas about cinema and was now focused on sharing entirely different ideas than he had been at any other point in his career. This was cemented two years later when Tetro released, a film concentrated on Vincent Gallo as the titular character who has reinvented himself in Buenos Aires in an attempt escape his past. When visited by his younger brother Bennie (played by Alden Ehrenreich in his first performance!), the new life that Tetro has built becomes more insecure, shaken at the foundations.

Coppola clearly never lost any of his directing power, and Tetro is proof of this – it has such a control over it, and the Buenos Aires setting along with the digital black and white ensure that the film is filled with plenty of beauty, too. Much like some of the other films on this list, there is a tension to Tetro, one that comes from the insecurity of the characters and the mysteriousness that their past carries, but overall the film is absolutely gorgeous and really marks the return of Coppola (Youth Without Youth is divisive, some seem to despise it).

7. Distant Voices, Still Lives (Terence Davies, 1988)

Maybe the best film on this list overall, Terence Davies’ ridiculously underrated and overlooked 1988 masterpiece Distant Voices, Still Lives is one of the best films ever produced. As we established earlier, Davies is one of, if not THE, greatest cinematic poet and Distant Voices is the greatest living proof of this statement.

Taking the deceptively simplistic story of a young man reflecting on his childhood after the passing of his abusive dad, but viewing it through such an abstract lens focusing in on presenting the memories in a way that is more surreal and dreamy than concrete, Davies manages to merge together those childhood memories with the present, making use of the sets and completely insane editing techniques as a way to blend the two together in a way so seamless it’s honestly a little hard to believe.

The entire film plays out as if it were imagined, nothing feeling even slightly clunky or out of place, it has an incredible inherent flow that makes it so smooth. The film is one hell of an emotional beating too, equally cathartic (especially during the scenes of singing, something that shows up in most of Davies’ films at one point or another) and heartbreaking, with this personal focus on memory that can be seen in the majority of Davies’ earlier work (especially in his trilogy of short films, which are semi-autobiographical and also utterly brilliant). Davies is one of the best directors to ever pick up a camera, and you really owe it to yourself to at the very least introduce yourself to one of his films and take it from there as a formal introduction.

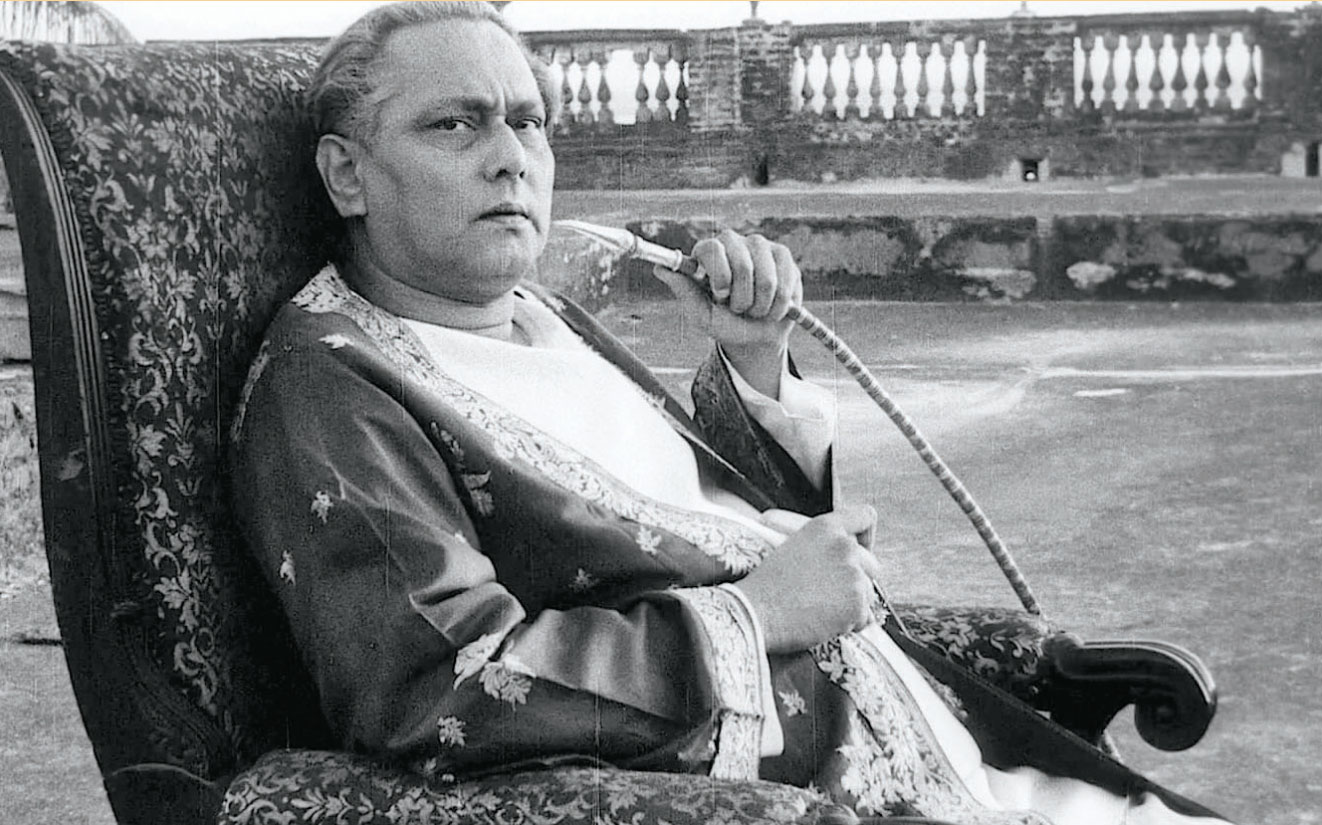

8. The Music Room (Satyajit Ray, 1958)

One of only two films shot on black and white film to make the list (my love for hyperactive colours is showing – it’s a wonder there isn’t any Brakhage on here!), Satyajit Ray’s 1958 tribute to the power of music as well as the harsh clash between tradition and modernity is as beautiful as it is sharply memorable and really quite depressing.

Following the life of an aristocrat (played by the great Chhabi Biswas) who has found himself feeling that his life has passed without him really realising it until too late, Ray’s film is focused on the desperate clinging to joy through art that comes when our other values are threatened. In the case of our fallen aristocrat, this artistic joy comes from his gorgeous titular music room, where he brings musicians to play for him as he relaxes and focuses on the sounds created. Made even more beautiful by Ray’s patient camera movements that glide around these flashback scenes like a ghost of the past, the film is unforgettable in the best way possible, and further enhanced by the brilliant restoration by the Criterion Collection a few years ago.

9. Beau Travail (Claire Denis, 1999)

French auteur Claire Denis probably doesn’t need much of an introduction thanks to her recent venture into American cinema for the first time with Robert Pattinson in High Life, but Beau Travail may remain her best work to date. Focusing on the strange beauty that comes with the male body and naturalism in general, largely thanks to the expressive cinematography of the brilliant Agnes Godard, Denis’ highly acclaimed 1999 film is one of the most visually stunning films of all time, and is the best film of 1999, too – a year full of cinematic gold. Denis Lavant, unsurprisingly, gives a phenomenal physical performance as sergeant-major Galoup, a man consumed by a need to get rid of new recruit Sentain to the point that he soon finds himself in ruin, too.

Much like La Cienaga, there is a dark tension under the alluring surface to this one, but the visual beauty seen here remains almost unprecedented, despite the continuous efforts of cinematographers around the world. The ending is also maybe the most liberating moment ever shot, and one of the most arrestingly beautiful – it is one of the finest endings of all time; a perfect summation of the themes and focuses of the film. Denis is a master, and this is one of her (many) masterpieces. It has to be seen!

10. Rhapsody in August (Akira Kurosawa, 1991)

Well, if you need swaying to seek this one out beyond the fact that it’s directed by the great Akira Kurosawa, it has to be said that Richard Gere is actually in this! Who would’ve thought? Concluding with one of the most overlooked works from the cinematic God that is Akira Kurosawa just feels right, just as Rhapsody in August feels quite inexplicably ‘right from start to finish. Set in the peaceful Japanese countryside and set with an incredible ensemble cast, Rhapsody in August is one of the most beautiful films ever made in terms of both its narrative and its visuals, focusing on themes of forgiveness and on moving forward in spite of great tragedy that may seem inescapable.

With a finale that strikes straight to the heart and a focus on family heavily reminiscent of the work of Yasujiro Ozu, Kurosawa is clearly trying something quite different than he usually would with Rhapsody in August, but it has to be said that in this case it pays off tenfold and makes one of the most surprisingly and emotionally resonant entries into his entire filmography. Rhapsody In August is one of the most beautiful films ever made, one so full of peace and simple mundane beauty that it’s difficult to forget even if you actively tried to do so. Very few films are like it.