Locations have the ability to define the momentum of movies. They can be both advantageous and disadvantageous; the way the director and crew use a location available to them completely shapes the nature of a film. That is the reason why specific spots have to be chosen carefully with just enough scrupulosity and sense of style in relation to the essence of the screenplay.

Sometimes filmmakers try to achieve a very specific tone, attitude, and mood that make them unable to drift back and forth in various locations. That is when they decide to create very clearly defined, overly distinctive sets and completely let them take over the spirit of their films.

Single-location films always tend to be much more dialogue-driven than ones with many filming spots; these kinds of films limit a viewer’s mind only to reflect on the images and voices introduced in front of them. Oftentimes, these films are full of existential questions and characters who doubt everything from their own identity to global politics.

1. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972)

One of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s most ambitious works, “The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant,” follows the titular character (Margit Carstensen) whose narcissistic nature and conceited aura overwhelms viewers. This four-act film is adapted from Fassbinder’s very own stage play. Theatrical origins can be detected through every lens, from its all-female cast to its avant-garde decorations.

The film is shot entirely in Petra’s room, with only a few transfers to other corners of her flaunting artsy apartment. This was, arguably, the greatest directorial choice made by Fassbinder since the film itself is emotionally one-dimensional with lots of questions regarding female identity that is socially perceived just as one-dimensionally as the film’s emotive beats.

Gender identity is the center of the film; however, characters present the complexity of how socially constructed models interfere with our most basic human desires. Power dynamics and role-playing between main characters never transcend Petra’s apartment. Petra’s and her assistant’s (Irm Hermann) silent, consensual role-playing somewhat evokes Jean Genet’s acclaimed theatrical piece “The Maids” despite the latter’s structural and emotional differences.

Each act represents perceptual and emotional shifts in Petra’s persona as well as her search for a sense of self. Her traumatic experiences are introduced quickly in the first act as she contemplates on them with her friend, Sidonie (Katrin Schaake). Her recent professional success is belied by her spiritual entrapment caused by damaging experiences. As everything fell apart and, at the same time, everything restored, her identity shattered and Petra found herself in the web of self-exploration.

2. Black Moon (1974)

“Mythological fairy tale taking place in the near future” – the way Louis Malle, director of “Black Moon,” described his recently released film back in 1974 is the perfect summary. This allegorical tale about a young girl’s sexual awakening amidst the cultural peak of European Second-Wave Feminism is loaded with twisted intellectual puzzles and ruminative metaphors. From the title itself (black moon – astrological symbol related to female sexuality) to its artistic references with Balthus (the main character, Lily, is often seen sitting in the same position as young girls from his erotically suggestive 1930s paintings), the film is challengingly riddled.

The most interesting fact to note is the film’s dreamy nature. Its clear surrealist leanings make a viewer astonished by the director’s ability not to limit the character’s dreamlike mindscapes roughly due to very small filming space. Malle very stubbornly strived to create phantasmagorical imagery with as few plot points as possible. He declared that whenever he verged on creating a plot of any kind, he would cross out his writings. Even though, at the beginning of the film, there are scenes outside of the film’s main location, I believe it can still be regarded as a single-location film.

3. My Dinner with Andre (1981)

Another Louis Malle masterpiece with few scenes outside of its main location deserves to be regarded as a single-location film because of its swallowing atmosphere and existential questionings.

Probably the most iconic, creatively stimulating, and intellectually tensioning dialogues takes place between Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory in the film’s very, very lengthy vivifying dialogue sequence. Shawn and Gregory, quite well-known artists of New York City’s experimental theater, play themselves. They meet each other after many years and discuss everything from creative tendencies to the decadence of contemporary arts.

4. Rope (1948)

One of the greatest technical achievements of Alfred Hitchcock, “The Rope” is adapted from Patrick Hamilton’s play of the same name. With its visual appearance of a single-shot film and Technicolor-soaked images, “The Rope” entirely inhabits a viewer’s mind with its dark psychological turns, twisted plot, and ghastly subject matter.

Loosely based on the case of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb who murdered the 14-year-old Bobby Franks in 1924 in an attempt to commit a “perfect murder,” Brandon Shaw (John Dali) and Phillip Morgan (Farley Granger) strangle their former classmate to death while also trying to prove their intellectual superiority by executing this so-called “perfect murder.” The most pervasive part of their unhealthy behavior consists of them throwing a party while having the corpse hidden in an enormous antique wooden chest – visible to any of their guests.

The presence of the hidden dead body in pretty much the center of their crowded majestic New York City apartment causes so much tension and suspense that viewers no longer acknowledge corrupted mindsets of main characters – they only want Rupert (James Stewart) to uncover the truth.

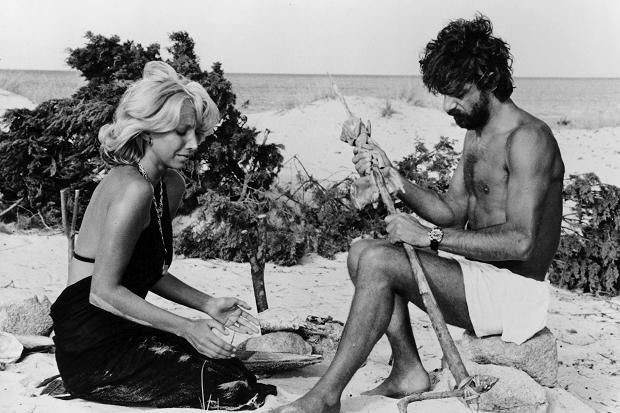

5. Swept Away (1974)

One of the greatest and most memorable clashes between capitalism and communism caught on camera. “Swept Away” starts with casual depictions of class struggle with two archetypical characters who personify conflicting ideologies, and grows into a sadomasochistic tale, packed with a handful of visual allegories about the flawed civilization and a deeply blooming desire for natural orders of the civilized.

The Mediterranean landscapes make it almost impossible for Rafaella (Mariangela Melato) and Gennarino (Giancarlo Giannini) not to start exploring their innate impulses in search for solace and survival in the part of the world that is not yet advanced.

Attacked by feminists countless times and adored by the Left for decades, “Swept Away” remains the masterpiece on the politics of power and cohesion expressed in the most lustful and amorous form possible.