Martial arts movies have long been one of most fruitful cinematic sub-genres, with movies that come from all around the globe; that are stylistically and aesthetically varied; that can go from family-friendly, comedic fare to hyper-violent dramas; but which are all united by the single quality of featuring stunning fight choreography and the best stunt work action cinema has to offer. Popular as the style may be, however, only the most mainstream (and usually West-oriented) movies ever transcend their already faithful fanbase to reach a wider audience.

Therefore, the films on this list may be familiar to genre connoisseurs, but for those who are mere casual watchers and are interested in discovering more about the early, formative classics and the best work from the foreign masters of the craft, then this assembly of titles will serve as a guide to explore more about this wonderful culture – and a path of no return into becoming a kung fu fanatic.

10. Legendary Weapons of China (1982)

The patron saints of martial arts cinema, the Shaw Brothers, at their height, were such a monumentally powerful force in Hong Kong filmmaking that their employees (directors, actors, writers, etc) slept in the studio lot, known as Movietown, just to keep up with the insane production schedule. This unprecedented level of productivity allowed them to release dozens of movies a year, with more than a thousand produced in the course of their entire run, many of which became some of the most beloved classics of the genre. Still, given the sheer volume of Shaw Brothers movies that exist, some of their very best ones still linger just shy of mainstream recognition.

Such is the case of “Legendary Weapons of China” (and a few others you’ll hear about on the rest of this list). Helmed by one of the greatest directors to have come out of Shaw Brothers, Lau Kar-leung (responsible for what is perhaps the most iconic movie of the studio, “The 36th Chamber of Shaolin”), the movie follows three representatives of different Boxer Rebellion factions, each with their own agendas, who are sent by the Empress to find and kill a former faction leader who disbanded his forces and is now hiding.

Though this set up infuses the narrative with a ticking-clock thriller element, as every agent tries to find the target before their opponent, the movie is actually fairly comedic in tone and, in some of the action scenes involving a troupe of pretend fighters, Lau plays around with his usual choreography skills and stretches his slapstick muscles (something he would perfect 12 years later with “Drunken Master II”). And speaking of which, the fight scenes, as expected, are the main attraction of “Legendary Weapons of China”: choreographed, shot, and edited with the director’s typical verve, creativity and energy; they are all quite spectacular, but none more so than the climatic duel that features the titular weapons and which is a prime example of the underrated potential of theses movies to expose and celebrate Chinese culture. Also, Gordon Liu plays an evil monk in it and, really, that’s reason enough to watch it.

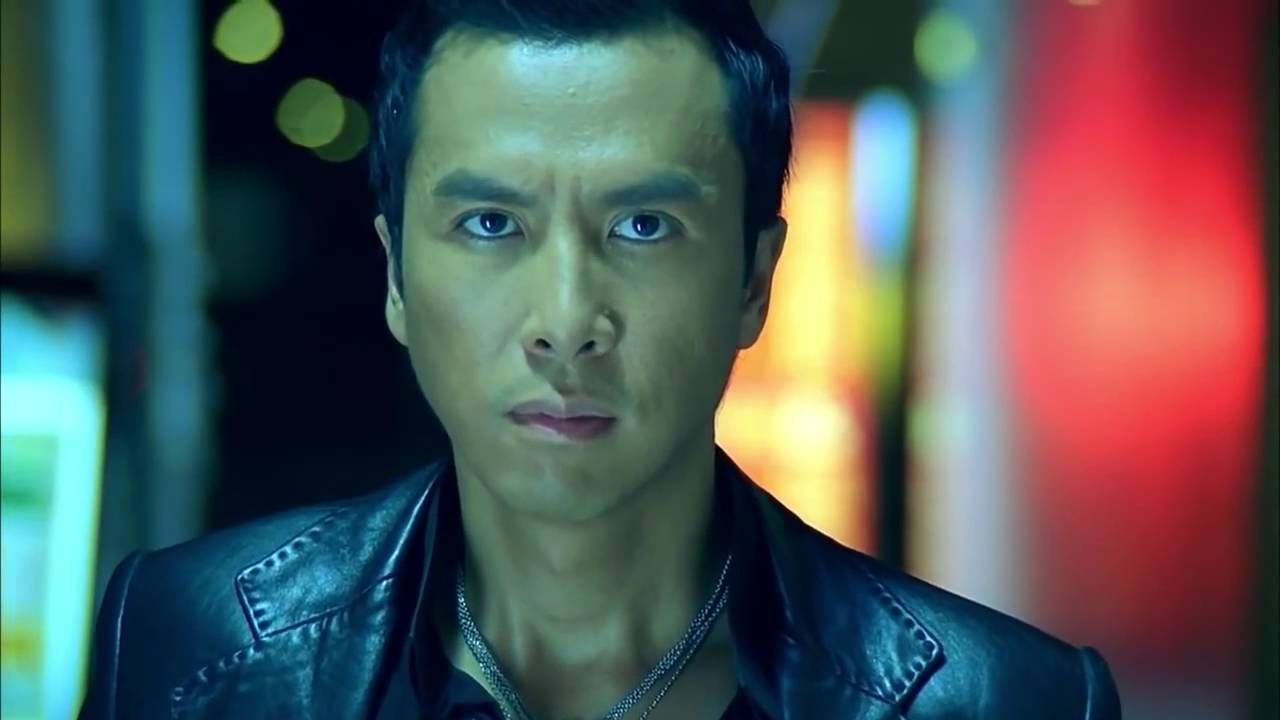

9. SPL: Kill Zone (2005)

A throwback to the Hong Kong heroic bloodshed classics from the ‘80s and ‘90s, “SPL: Kill Zone” substitutes the usual gunplay of this type of movie for intense hand-to-hand combat, but maintains all the other ingredients of the genre: the melodramatic sensibility toward character and theme, a melancholic examination of violent men and their codes, and of course, the sudden bursts of operatic and bloody violence.

The film stars Simon Yam as a terminally ill detective, in his last days on the job, resorting to illegal means to settle a score with triad boss Wang Po (played by martial arts icon Sammo Hung) and Donnie Yen as the officer sent to take over the unit from him. From there, the confrontations between the characters on different sides of the law keep escalating just as the lines that separate them become blurrier.

Though it has a few interesting things to say about the moral bankruptcy of the police force, the movie isn’t particularly interested in social commentary; instead, it aims to register on a more visceral emotional level. It’s an extremely macho movie, of course, but, like the John Woo and Ringo Lam flicks that inspired it, it manages to find the flaws and vulnerabilities in the characters’ way of thinking and it eventually morphs into a meditation on fatherhood and the emotional cost of leading a violent life.

The fight sequences are not as abundant as in most martial arts movies, but they compensate in quality what they lack in quantity: choreographed by Donnie Yen himself, they are staged by director Wilson Yip (who also collaborated with Yen in the hugely popular “Ip Man” movies) to highlight the intense physicality of the combats, resulting in some of the most brutal fight sequences you’ll ever see this side of “The Raid.” A few years ago the movie got a largely unrelated but equally excellent sequel, which is also highly recommended.

8. Five Element Ninjas (1982)

Another Shaw Brothers flick, this one directed by the filmmaker who, alongside Lau Kar-leung, is the most synonymous with the studio: Chang Cheh. Having basically invented the modern wuxia with ‘One Armed Swordsman,” Cheh spent the following decades delivering a few of the greatest entries in the kung fu canon, like “Five Deadly Venoms” and, with this movie, proved that even in the final stages of his legendary career he could still deliver.

The plot is fairly simple: a martial arts school hires Japanese ninjas to destroy a more successful rival school. The resulting massacre has only one survivor and he swears to study the ninja’s techniques to get revenge for his master and fellow students.

By the time “Five Element Ninjas” was made, Cheh had already directed dozens of martial arts movies and so, with this film, he seemed to be trying to go stylistically further than he had ever gone before, be it in the extremely expressive use of color (each of the titular elements is color coded and made to pop at the screen, a sort of prototype of what Zhang Yimou would do years later with “Hero”) or in the amount of gore that, even by Che’s more violent standards, is really something else here. In the fight scenes, bodies are dismembered and blood splatters out of victims in showers of crimson, a level of brutality that was unusual for Shaw Brothers movies. But Cheh gets away with making a very heightened movie that isn’t restrained by the boundaries of reality and, because of that, the violence here is not shocking or unpleasant, it’s just a natural extension of the elaborate kung fu choreography.

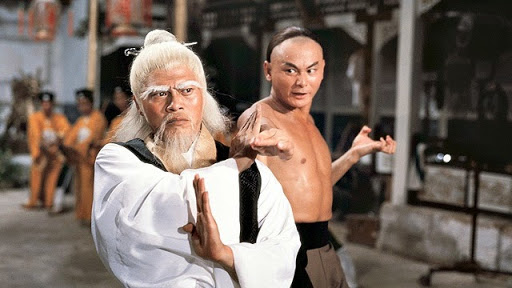

6 & 7 – Executioners from Shaolin (1977) / Fists of the White Lotus (1980)

These two will come together due to the fact that, though nominally a sequel, one is basically a remake of the other and watching them back-to-back makes for an interesting experiment in seeing how different filmmakers can find slightly different variations on the same framework of a narrative.

In both movies, an evil priest (Pai Mei in “Executioners from Shaolin” and his “brother” White Lotus in “Fists of the White Lotus”, but really, it’s the exact same character) destroys a Shaolin temple and the remaining survivors band together to train and take revenge on him. But it’s not that easy: the priest’s kung fu skills are unmatched and defeating him will take a lot of work.

“Executioners of Shaolin,” another Lau Kar-leung film, was the first to come out, and what makes it distinct and memorable is how unusual the revenge narrative is. This a multigenerational story; the protagonist spends his entire adult life fighting and losing to Pai Mei, gets married, has a son, and still hasn’t cracked how to defeat the man. And so it becomes the child’s responsibility to finish his father’s work, an interesting spin on the generic retribution type story.

“Fists of the White Lotus,” on the other hand, distinguishes itself by playing a heavier focus on the actual mechanics and techniques of kung fu and what it takes to improve your skills. As the main character in this one also finds himself again and again bested by the villain, he keeps trying new methods and fighting styles. It’s an excellent progression movie: in each new combat, the improvement of the hero’s abilities is clearly visible, a triumph of action choreography as storytelling.

The main attraction in both movies, however, is the same: the villain. Pai Mei/White Lotus may very well be the greatest antagonist in a martial arts’ movie ever: his look is so iconic, and his sheer evilness so unparalleled, that it’s no wonder Tarantino couldn’t resist making him a key part of “Kill Bill.”