6. Diary of a Lost Girl (G.W. Pabst, 1929)

One of the most beautiful silent films ever made, G.W. Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl follows the story of Thymiane Henning (played by Louise Brooks in a spellbinding performance), a girl who becomes pregnant after being raped and therefore finds herself deserted by her family and forced to fend for herself in a world that wants very little to do with her for no reason of her own doing.

It’s a very harsh film, but God, it’s so good. If anyone is looking for a way to get into silent films, this one is bound to help as the emotion involved in the story (and especially in Louise Brooks’ mesmerising performance). It’s a real classic, but also one that deserves much more attention and acclaim for what it says and how it chooses to say it. A truly beautiful movie, even if some of it is hard to watch.

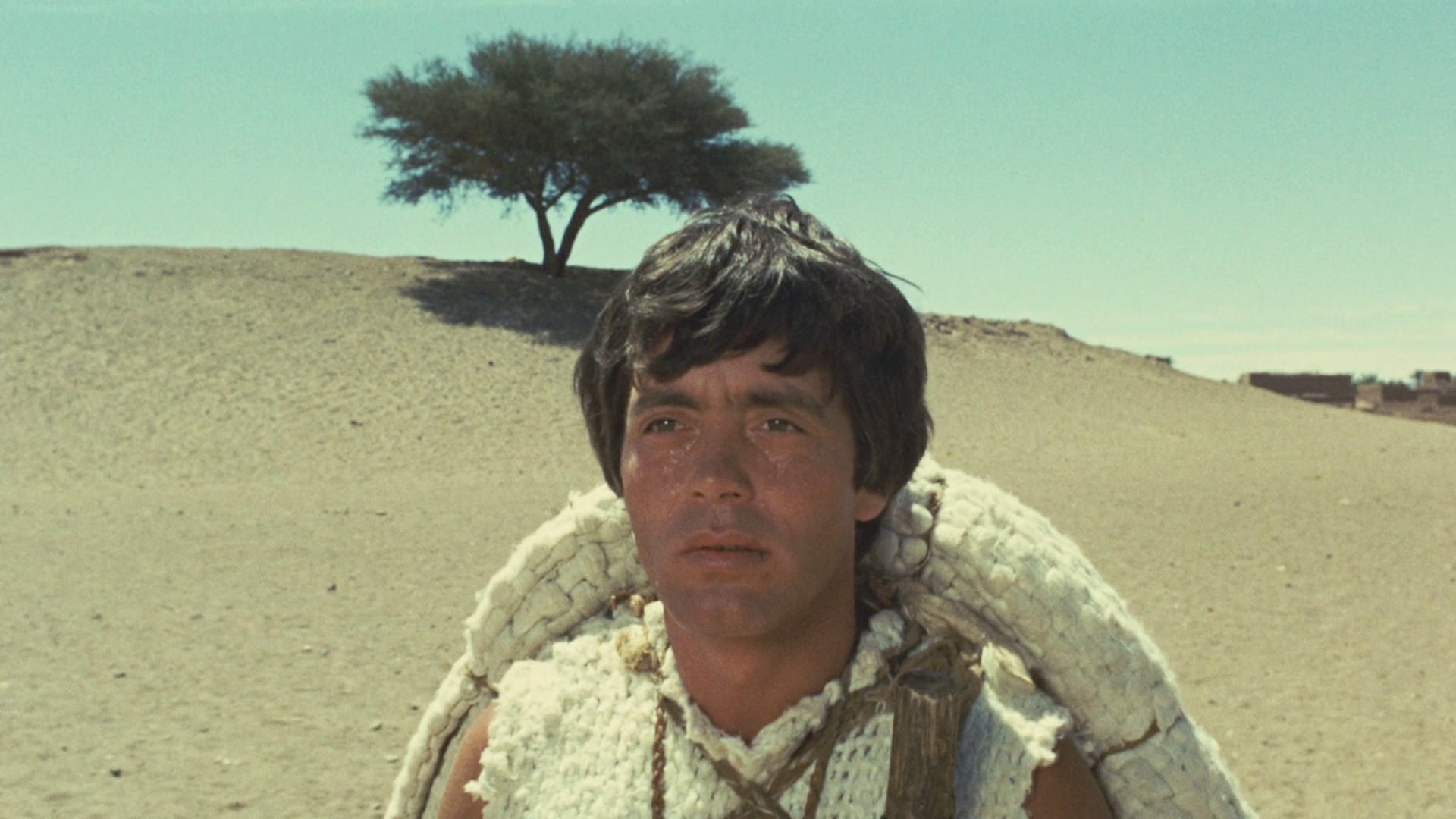

7. Oedipus Rex (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1967)

Pier Paolo Pasolini probably needs no introduction – the fearless, endlessly cheeky political mastermind has definitely made a name for himself that has given him immortality through his controversial but brilliant work, and Oedipus Rex is no exception to the rule that says that Pasolini outrages his audiences.

Working from Sophocles’ classical Greek tragedy King Oedipus, adding and extending many parts for the sake of simply spending more time with these characters, but also updating the myth with the opening and closing chapters by placing it in present day and effectively chuckling at how little has really changed since the so-called barbarian times, Pasolini creates an incredible adaptation of one of the best texts in literature whilst also still adding his trademark style as he did when he adapted The Canterbury Tales, too. Taking these texts and making them his own most definitely made him more infamous to audiences who are more prescriptivist about adapting texts, but the wonder of Pasolini is that he didn’t care about that, he just wanted to make great movies.

8. Carmen Jones (Otto Preminger, 1954)

One of the earliest mainstream films with an all black cast, Carmen Jones isn’t perfect but is damn surprisingly nonetheless. A beautiful musical focused on the story of the titular femme fatale Carmen Jones, this film is another rare product of its time that stands out so much now because of the risk it took at the time. It’s a fascinating film to see being aware of the context, and much like Watkins’ Punishment Park, there’ll probably never be anything quite like it again.

Otto Preminger always seems to go all out on his projects, and this one is no exception. As problematic as some parts of this is, a lot of it stands together surprisingly well considering this film is approaching its 70 year anniversary, and the musical numbers are great. It’s no masterpiece, but it is damn good!

9. Thieves’ Highway (Jules Dassin, 1949)

Jules Dassin generally is really quite overlooked with the exception of Rififi, and it’s a real shame as he is one of the more unique film noir directors (in that he often strayed from the typical femme fatales and drenching his films in smoke). Night and the City has a distinctly gripping grit to it throughout that makes its conman focus feel all the more real, and it makes for an electrifying thriller, but Thieves’ Highway may just be even better.

Focusing on the story of Nick Garcos, a Greek man who returns from World War II and finds that his father has been conned and almost killed by a food salesman and swears revenge, Thieves’ Highway intently stares at (maybe glaring at would be accurate) the corruption that comes alongside money, something explored in the majority of Dassin’s films, as well as this darker connection between money and classical Greek tragedy.

Multiple Dassin films are framed similarly to Greek tragedies, and so it can’t be a coincidence that so often he chooses to place Greek characters into his narratives, making a condemning connection between his characters, who always try to do their best, even if it is in vain. Night and the City bears clear resemblance to the story of Sisyphus, and Thieves’ Highway is quite similar, also acting as a clearly large influence on Henri-Georges Clouzot’s incredible The Wages of Fear, which came out just a few years after this one did in 1953 and focuses on a startlingly similar narrative (along with all of the startlingly similar ideas that come with it).

Dassin’s film is a hell of a ride, unfortunately overshadowed by those who took some of its ideas and ran in a different direction with them, making use of bigger budgets to bring in double the excitement and therefore doubling down on the impact of Dassin’s original message. Nonetheless, Thieves’ Highway shouldn’t be skipped over, as it is brilliant, it’s just a little harder to find now.

10. Rhapsody in August (Akira Kurosawa, 1991)

Legendary director Akira Kurosawa’s penultimate film, Rhapsody in August makes for one of the most beautiful dramas ever made. Taking plenty of inspiration from Yasujiro Ozu with the focus on family and connection, but maintaining Akira’s usual style with the almost constantly gliding camera and the odd casting (more of a trait of Kurosawa’s late work, but still – Richard Gere shows up in this film, and has a key part – who would’ve thought?), Rhapsody in August is about a Japanese family who has to confront their troubled past with America (left over from the impact of the grandmother having been alive during, and lost her husband to, the Hiroshima bomb) when she wishes to visit her long lost brother who is hospitalised there.

Bringing such grace and beauty to the world of Kurosawa’s films, and mixing it with such a beautiful story, too, Kurosawa saved one of his finest films (certainly his most beautiful!) for close to the end of his career. This film is impossibly beautiful, and is so frequently skipped over by Kurosawa’s fans for some reason… so, if you enjoy Kurosawa, do see it! Hell, why not see it even if you don’t like Kurosawa – it deserves the attention any way it can be received!