The first shot of a movie often has an enormous transcendence regarding the audience’s first impression and judgment of it. It is the first visual glimpse of this new reality the spectator is being pushed into. It does make a great difference if it is a steady shot, a sequence shot; if it contains voice-over or dialogue.

The complicated but often rewarded conception of an exquisite opening scene is fundamental for the early judgment of the audience; if a character is presented in media res everybody will try to discover who that is through the entire movie, or if a key event for the plot is developed initially, as it happens in some of the films in this list, its initial shot will become crucial and be specially kept in the spectator’s memory to understand the development rest of the movie.

All in all, a good opening scene, an initial shot that takes your breath away by suggesting without explaining too much, just makes a movie better. In this list, you will be able to find some great movies that contain even greater opening scenes.

1. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

The audience is introduced to the movie through steady red shots that paint the screen in the first seconds, while ominous music is playing and a certain tension for the upcoming images plays a decisive role. Once the title and director credits have appeared in a monumental but cryptical way, the screen switches to the first shot. And what a first shot. A young man with a creepy fearless look is looking straight to camera, his blue ocean eyes are almost covered by his rounded hat and artificial eyebrows, but there is no doubt in his look.

This emotional intensity that Alex spreads is magnified once the shot is opened and the location of the character is unveiled. By using a sequence shot, the strangeness and absurdity of the Korova Milk Bar are firstly presented, as the audience finds out who the rest of the characters are. Additionally, almost at the end of the opening scene, Alex’s voice over appears. He presents himself along with his best friends, the uniqueness of the Milk Bar and finally, their way of living: ultraviolence.

There are countless reasons to consider this one of the great scenes in film history. Nevertheless, most importantly it immediately succeeds in catching the audience’s attention. The bizarre and eccentric set design of the bar along with the almost funny but extremely queer clothes of the characters portray an excellent presentation of what the plot will end up developing. The scene does not explain excessively, but it gives a remarkable glimpse of what is coming next.

2. Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

The camera explores the underwater. Contrary to the friendly National Geographic documentary precedent Jaws’ extraordinary initial montage stresses the nature of the upcoming scenes. With a nervous music orchestra that seems to be following the camera’s footsteps, the title of the movie and the initial credits all quickly appear underwater, and of course, that will have an indirect significance developed a few shots later.

With a straight cut, the camera now watches a group of young people talking, laughing and partying around a fire on a beach after sunset. Two of them look at each other as if announcing a coming fleshly new romantic relationship. Then, the girl starts running while taking her clothes off near a long fence that ends in the ocean. As expected, the boy clumsily follows her trying to figure out her identity.

Although this could appear to be the first encounter of a young couple in a privileged environment, through the attacking music and the wide and dark photography of the shots Spielberg is already setting the elements for something unexpected and bad ti happen. And so, it does. After a few moments of a swim, the girl is attacked by what could be a shark (we are not shown the animal itself yet) and the boy is incapable of rescuing her.

To create this noteworthy first sequence, Spielberg adopts the constant cut of the editing and the slow fade-in of the music we have already been introduced to grow the tension, which is a key aspect for Jaws to work. Ultimately, through the fast pace of a tragic two people story, Spielberg lights the fire of the fear for the sea (and for the unknown) he will develop in every scene that follows.

3. Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958)

Though a sophisticatedly calibrated black and white wide shot, Touch of Evil starts with the anonymous activation of a mysterious bomb, that will start a repetitive ticking noise, placed on the back of a convertible car. Again, shot as a sequence, the audience is introduced to the US border with Mexico by two parallel stories: a young and freshly married couple walking through the border and another one driving and crossing the frontier by car. Friendly music is always playing to increase the strain under the explosion of the bomb: will it happen? Will it kill the couple? Will they notice it beforehand?

Orson Wells proved in this exquisite opening sequence, that tension can not only grow through parallel editing; long sequence shots that masterfully and physically switch between two stories happening at the same moment can indeed stress the outcome of the scene. This opening scene is beautiful to look at, it creates a precedent for the mystery plot that will be revealed later on, and it works through building on the duality of characters, couples, and countries.

4. Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968)

This crepuscular start of the featured Sergio Leone western Once Upon a Time in the West is worth mentioning, as it takes a different path compared to the previously commented movies in this list. Unlike the others, this opening scene not only is intended to present a bunch of characters, a specific location setting or a particular plot point of the film, but it is also voluntarily an extended sequence where nothing happens.

There are no shots, no movement, no words said out loud. And there is no need for those things, because the images, slowly cut from one to another, speak for themselves. In addition, this is indeed one of the longest if not the longest, opening sequence in this list as it takes almost seven minutes for the train to finally arrive.

If music was somehow a decisive element in the previously commented opening scenes, the sound is a key device here as well. From the repetitive wind turbine noise to the annoying fly or the growing sound of crickets around the area, the sequence creates its own soundtrack with diegetic casual noises that happen on screen.

It is also unquestionable that although the sequence is extremely slow-paced, and the camera takes its time to capture this prolonged temporality, the scenes build up an interior tension that the characters express through their eyes and look. This fresh approach of slow temporality as a way to create a growing tension without any particular focus makes this opening scene one of the best in the western genre history.

5. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

The dawn of man. The beginning of mankind. This is the title Kubrick himself gave to the opening scene of a movie that announced a new era for the film industry and for developed societies: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Although this may be one of the most quoted movies ever, there are many reasons that somehow justify so. The prelude, the introduction of this nearly 3 hour-long science fiction experiment is a short movie on itself.

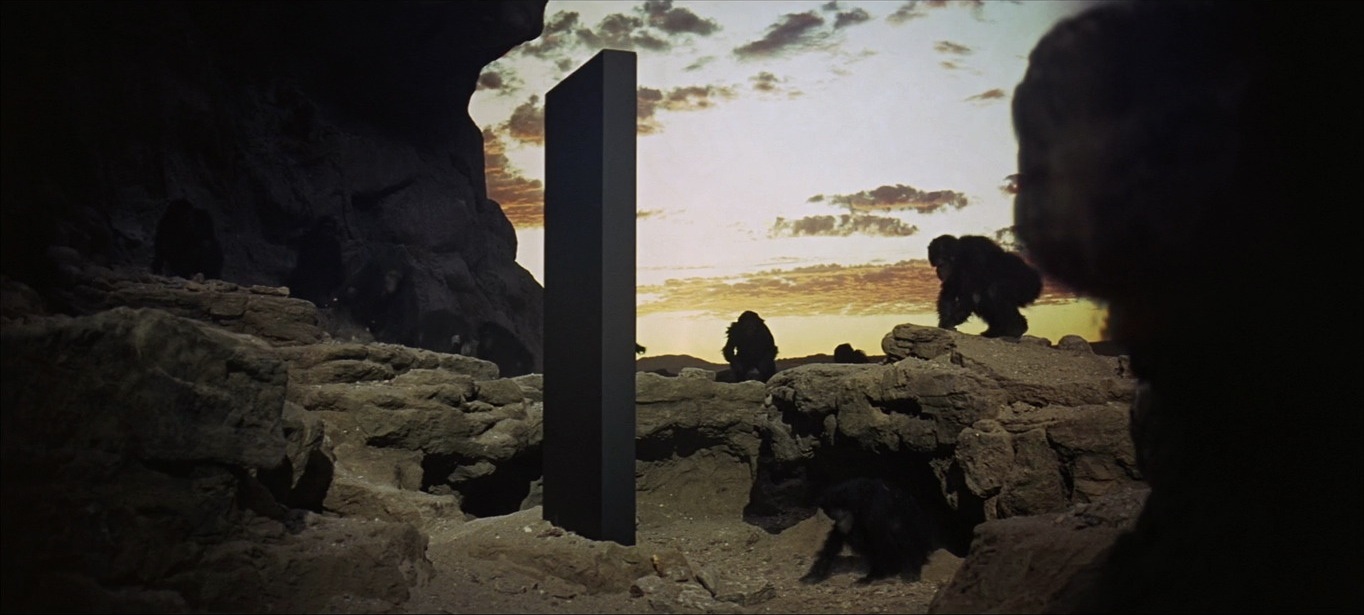

Two established groups of gorillas fight upon a small lake of water in desertic surroundings, until a cryptically futuristic blank monolith appears, all of a sudden, just above it as a random gift. This symbol of human intelligence is the cause for one of the gorillas to discover the ability to create a murder tool using only a bone. Through intelligence we find wisdom. Using bones as weapons, the group of gorillas will conquer the lake where they had previously been expelled from. In the end, a bone is thrown to fly in the sky, and this led to the longest temporal ellipse in film history. From prehistory to 2001.

The monolith works as a metaphor of metaphors, as an indicator of artificial life impossibly placed in a primitive era. This builds up to be a brilliantly brave experiment that no other filmmaker has dared to reproduce or imitate. It is not a presentation of the space of characters, it is the symbolic key to the questions the movie will probably leave unanswered later on.