There is something inherently cinematic in the road trip. In the travelogue of sights, in the ever-changing surroundings and continuous road, the compression of space – city after city – and the expansion of time – the monotony of travel itself. In the way travel makes one perpetually a foreigner, newly attuned to each passing image of the everyday. In the self-contained, often symmetrical structure of the trip that lends itself so easily to narrative structure, that makes of the destination a symbol. In the at-hand mythologies of the open road as a place of freedom, possibility, and exile, of travel as a passage of self-discovery, and in the harsh realities that lie beneath them.

This is the basis for the road movie, the generic use of travel as both a production tactic and a foundation for narrative. The plot of the road movie half writes itself in the getting from A to B, whatever internal movements the characters are undergoing become mapped onto the road itself, and the confinement of travel companions together makes for just the kind of hothouse atmosphere to bring idle talk and latent tensions spilling forth into conflict.

Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 Wild Strawberries is a perfect example of the road movie in its classical form, where the Scrooge-like Professor Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) receiving an award in celebration of his career sets off on a trip from Stockholm to Lund with his estranged daughter-in-law Marianne (Ingrid Thulin) to accept it. On the road Borg is stirred by vivid dreams into confronting demons from his past long since repressed and is reminded of happier times by a young hitchhiker Sara (Bibi Andersson) who reminds him of a young love his own, and given the time and the rejuvenating power of travel Borg is able to work things out with Marianne. As goes the maxim the journey turns out to be more important than the destination. The award, when Borg finally accepts it, no longer means a thing to him, far more important is his newfound peace of mind.

Conveniently heartwarming. So as often as redemptive the road is portrayed as an unforgiving place of broken dreams, of struggle, hopelessness, and death. This is the strain of pessimism found in what might be the quintessential American road movie, Dennis Hopper’s 1969 Easy Rider. Though remembered best for the exuberance of its freewheeling first half, Easy Rider is essentially the tragedy of a duo of hippie bikers (Hopper and Peter Fonda) setting out from LA to New Orleans for the festival Mardia Gras and, indirectly, to find the American dream. Instead they find brutality and death at the hands of intolerant locals. The American dream is dead, Easy Rider says, if it were ever alive to begin with.

But then there is a different kind of road movie for a different kind of road, one where the trip has no end in mind, where destinations come and go, without any hope attached. These are films wherein the road is only a path of flight, where those who travel out on it are given to perpetual drifting and self-destruction. These are films that share a focus on the facts of the road itself, not the narrative that runs through or over it – the texture of travel – roaring engines, the long cycle of days, anonymous motels, bars, and faces, and the feelings of rootlessness and disaffection that put one out on it.

Here are 10 road movies without destination to get lost with.

1. Two-Lane Blacktop (1971)

Monte Hellman’s 1971 Two-Lane Blacktop is a film about driving. Its heroes – one driver (James Taylor) and one mechanic (Dennis Wilson) are drag racers. They take their beefed-up Chevy 150 up and down the endless asphalt of America’s main street, Route 66.

They have neither names nor personalities nor long term goals to speak of. The two men are inseparable from their roles. The car is their concern. They speak in grease monkey jargon, only practicalities. They size up passing cars and scope out small towns for action. They race for money and they race to win. Racing is their work, their sustenance, their fulfillment. Life is easy when reduced to one single purpose. The American myth of the drifter gutted to its purest zen devotion to emptiness.

Two potential foils enter the scene and threaten to shake the racers from their ascetic convictions. The driver of a sporty new GTO (Warren Oates) meets them at a filling station and challenges them to a cross country race. The 150 accepts. GTO turns out to be mostly talk. A recent dropout, a mid-life crisis case packed up and left on a brand new pair of wheels, picking up hitchhikers and looking for adventure. The road is going to crush him. While the duo sits inside a diner a young hitchhiker girl (Laurie Bird) hops out of a van and stows away in the back seat of their car. They don’t ask questions, she rides along with them. She’s like them, devoted to the road. She has more to say, but no more hopes or dreams. But as she begins pulling at the affections of both, and seems about to insert some jealousy between the racers she’s off on the back of someone else’s motorcycle, unable to afford the attachment herself.

Shot in long panoramic takes with an observational naturalism Two-Lane Blacktop is a beautiful and ambiguous meditation on the American drifter no longer seeking but persisting.

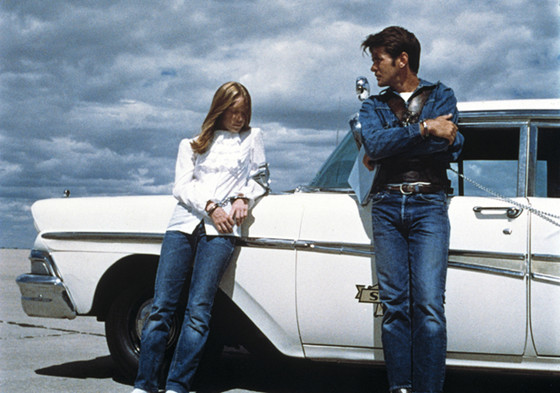

2. Badlands (1973)

1973’s Badlands, the first feature of writer-director Terrence Malick who has since made a name for himself as a director of grand sweeping epics like The Thin Red Line (1988) and The Tree of Life (2011) began his career as director with this lowkey, irreverent, lovers-on-the-run movie inspired by the 1958 killing spree of young Texans Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate.

Martin Sheen is Kit, a garbage man who fancies himself something like James Dean, and Sissy Spacek is Holly, a baton girl and Kit’s partner in crime. The film starts in innocence, in the world of a young couple playing at being outlaws in the closed world of their sleepy small town – but somehow remains there, even as the killing starts. Kit kills Holly’s father (Warren Oates) when he tries to keep the two apart – and setting off on the road he continues – trigger happy – finding reasons to kill folk. Open-air, daylight, and youth seem to make good clean fun out of killing. Malick never attaches too much weight or darkness to the murders. It’s all part of the game. Death is something contingent, mundane, unreal, and far away. There’s never any sense the two are in any danger. Between murders Holly muses plainly on who the man she’s going to marry’s going to be – apparently unaware she has locked herself into an anything but plain life as likely to end in imprisonment as death. Everything’s void and lighter than air. And the game only needs to end when it stops being fun.

With its painterly vision of the American plains from South Dakota up toward Alberta, idyllic tone, and scoring by Carl Orff’s playful “Gassenhauer”, Badlands is a strange and haunting fairytale of the road.

3. Lost In America (1985)

Lost in America is a 1985 comedy from actor-director Albert Brooks which lampoons the romance of the road with its tale of a delusional yuppie couple David and Linda (Brooks and Julie Hagerty) who, seizing upon the emotion of David’s losing a big promotion at work, decide to sell everything they have to pursue a simple life out on the road, to ‘find themselves’ and ‘live like savages’ just like in David’s favorite movie Easy Rider – apparently forgetting how that movie ends.

Renouncing their worldly possessions – save for a half a million dollar “nest egg”, and the decked out Winnebago camper they buy in place of motorcycles, the two set off out of LA toward Las Vegas, trying to convince themselves of the rightness of their decision.

But high on the impulsivity of dropping out Linda quickly loses everything they have in a manic roulette losing streak. Now without their safety net and faced with the possibility of actually living the life of freedom the couple claimed to seek, the two in turn break down completely, David into rage, Linda into a nervous doubling down into the road life they have chosen. Through their travels David tells anyone he can about his dropping out, bothered by the apparent lack of reception. In fact the only one who seems to care is a motorcycle cop who pulls him over for speeding, and turns out to be a big Easy Rider fan. “Remember the ending?” he asks “Where they got blown away? That made my day!”

Lost in America is not only a reflection of a 1980’s cynicism toward the naive idealism of the 1960s and the redemptive potential of the travel as seen in classic road movies, but also a satire on the yuppie couple’s total lack of self-awareness and the essential compatibility of their shallow materialism with the ideals of simple living they in their youth professed – their inability to admit or even recognize their own selling out.

4. It’s Impossible To Learn To Plow By Reading Books (1988)

Richard Linklater’s 1988 debut feature It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow By Reading Books is a one-man 8mm travelogue of the American West and Midwest starring Linklater himself as the film’s unnamed protagonist – less a character than a symbol, a kind of man without qualities. The film is shot in a series of long static takes emptied of overt action, full of voices, but more as sound than dialogue. It is a film not only skeptical of the road but apparently skeptical of narrative in general – an ‘oblique narrative of alienation’, in Linklater’s words. A meditation on travel – on foot, by car, by train, and an experiment in elliptical storytelling.

The film opens with Linklater in Austin receiving and listening to a rambling tape-recorded message from a distant friend (James Goodwin) in the Missoula Valley. It is an indirect invitation to blow off school and come visit. The film spends some time on Linklater at home going through the motions of his mundane existence – washing dishes, doing laundry, buying groceries, the banal realities of life usually kept out of movies. Finally a decision is made, and Linklater takes to the road to travel through an indistinguishable America of railyards, bus stations, and bars, where travel reveals itself not to be any escape from the everyday but just another extension of it. Linklater spends the film drifting through a loose network of friends and acquaintances, talking about nothing, watching movies and quoting from books that express more of their inner worlds than their alienated voices could, drinking beer, playing basketball, talking to strangers, and generally killing time.

In one scene Linklater and Goodwin go for a hike up to a local lookout point, the Missoula ‘M’, and reaching the top fall back exhausted on the hillside. We expect the camera to point out at the vista they have worked so hard to reach, but it only peers back up the mountain at the two of them. Linklater himself does not even take a look, laying back staring up at the sky asking “Why’d we do this? Come up here?” James’ answer might be the thesis of the film. “Gotta do something.”

5. Wanda (1970)

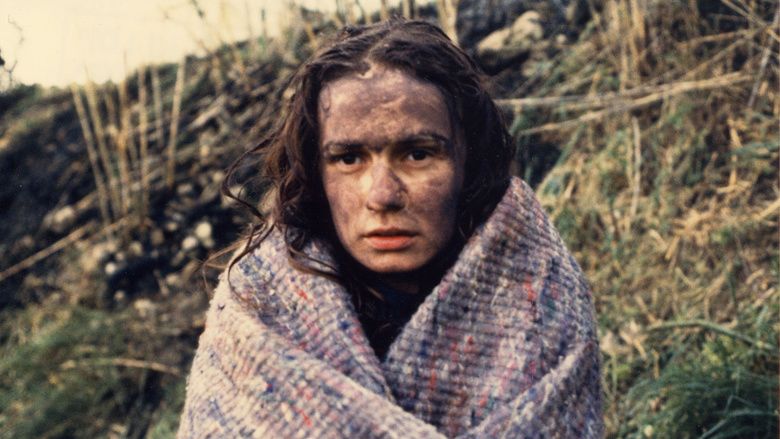

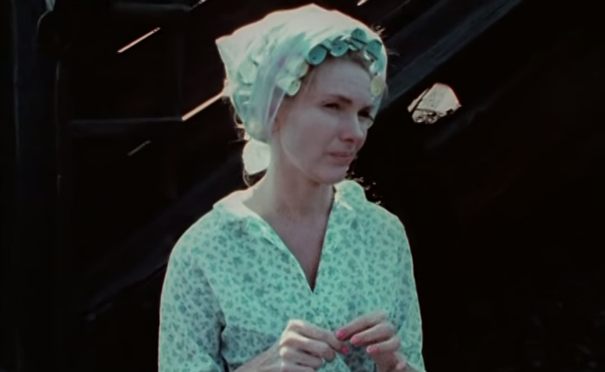

Barbara Loden’s 1970 Wanda was the actress’ only directorial work and stars herself as Wanda Goronski, an absent minded and apathetic woman drifting across Eastern Pennsylvania. Called ‘the female Cassavetes’ at the time Loden directs with a handheld verite style but affects a comic and spontaneous realism all her own.

The film opens on the day of Wanda’ divorce hearing, to which she shows up late and gives no fight when her husband argues for full custody of the children. She doesn’t care any. Wanda shows up to work asking for some money only to find she has been fired for not working fast enough. Her boss talks down to her like a child and out of conditioned politeness she thanks him on the way out.

Now without family or home and accountable to none Wanda begins to wander around. She asks for money, lets strangers buy her beer and food, and sleeps with men for a place to sleep, floating vacantly place to place hitching a ride or tagging along with whoever she can. Eventually she falls in with a petty crook Mr. Dennis (Joe Dennis) who she meets on entering a bar he is in the process of robbing. She doesn’t seem to notice and asks Mr. Dennis for a drink, who, suspicious, serves her. She goes home with him. He takes to her like an alcoholic dad. Wanda and Dennis drive around the state in his Chevy Bel Air. Dennis has ideals, like money, and ambitions, like stealing it – designs on a bank robbery. Wanda can’t be bothered. She has nothing, she wants nothing. She thinks she might be dead.

There is something long broken in Wanda – too readily deferring, too passive, apologetic. The world takes advantage of her time and time again. But there is something redemptive in her total indifference too. She is immune to the expectations and responsibilities of the world. In her receptiveness, she is provided for. In her lack of desire, she is free.