All cinema is current.

It’s not just modern releases or the films scooping Oscars and BAFTAs that are part of our ongoing cinematic imagination; it’s also those films that we discover from the past. Seen for the first time, they can seem as surprising, challenging, and that dread word, relevant, as anything at the local multiplex, because while old hat to many, they are new to us. They inspire fresh ways of looking and perceiving, and offer an alternative perspective on the present, perhaps even a challenge to it.

Last year, Orson Welles’ film, The Other Side Of The Wind, was finally completed by a team of editors, and therefore entered the cinema landscape as a new film, though wholly of the 1970s, the fact that it had never seen light before, except in clips, meant it was as new an artefact to filmgoers as the latest Marvel blockbuster. As such, its blunt sexual politics, jagged editing and bold film-within-a-film structure seemed of a piece with two time zones at once, a large part of its fascination deriving from the way its hybrid composition confronted the mores of both eras simultaneously.

The following list is not just made up of titles discovered by one individual only, but like The Other Side Of The Wind, ones re-encountered by the whole cinephile community at the same time. Whether through a restored print shown at festivals or a wide blu-ray release after many years, these films have enjoyed a new lease of life in the 2010s, forcing critics and fans to revise their assumptions and reassess the canon.

1. Ganja and Hess (Bill Gunn, 1973)

As diversity became the watchword of the decade, and the myth took hold in the popular media that challenging films from non-white filmmakers had been in scarce supply until now, this forgotten vampire flick of the 1970s came back to haunt us. At least it was meant to be a vampire film; the producer asked actor-director Gunn to cash in on the blaxpoitation craze of the ’70s by creating a bloodsucking counterpart to Shaft et al. But Gunn was more ambitious and used vampirism as a mere pretext to explore more contemporary issues such as addiction, feminism, and the African-American’s relationship with the home continent.

As such, Ganja and Hess became a fascinating mix of horror tropes, black comic satire and mature reflection, as it told the story of a professor returning from Africa under the influence of a spell which gives him a craving for blood. What is most striking to the modern viewer is how the film’s outsider status in the ’70s gave it the leeway to be more raw and confrontational than most films made in the mainstream by black filmmakers today.

2. Invention For Destruction (Karel Zeman, 1958)

While it’s exciting to rediscover forgotten films, it’s even more exciting to rediscover a forgotten artist, and to see all their works slowly resurface. Karel Zeman’s animation is beloved in the Czech Republic, but fell out of view in the west until recently, when enterprising Blu-Ray publishers, like Second Run in the UK, started to release restorations on disc. This Jules Verne-esque adventure, about pirates stealing the plans for a super missile, and his fantastic adaptation of The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1961) are the cream of the crop.

The debt owed to Zeman by Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam and other animators is clear to see, the characters and backgrounds like the illustrations from a Victorian gentleman’s magazine come to life. Humour rubs shoulders with romance and high fantasy, as live-action actors interact seamlessly with a world of giant squid, wooden submarines, and evil lairs on volcanic islands.

3. Underground (Anthony Asquith, 1928)

Unlike Zeman, Asquith wasn’t so much rediscovered this decade, he’d long been registered in the annals of British cinemas as the maker of slightly stuffy middle-class dramas as entirely reassessed. Because there was a young Asquith, a relentlessly playful and experimental silent filmmaker, whose work had been completely hidden for almost 80 years.

The BFI restored three of his earliest films, Underground, Shooting Stars (also 1928), and A Cottage On Dartmoor (1929), and all three turned out to be minor masterpieces, in thrall to the possibilities of the medium and exploiting them with freedom and zest. Underground, a girl-and-two-boys story set in and around the London Tube, and which ends in tragedy, is arguably the finest of the three, but all display a remarkable mastery of camera, location and editing.

4. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Miss Osbourne (Walerian Borowczyk, 1981)

Other rediscoveries allowed us fresh perspectives not only on their directors, but on well-known, apparently exhausted tales. Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde is reputedly the most filmed story of all time, but Borowczyk’s free adaptation still manages to be a revelation, with its genuinely disturbing prologue showing the pursuit and beating of a child, its haunting modernist score, its leering, hysterical sex scenes and yet at the same time its streak of unexpected feminism, as the focus turns more on Jekyll’s intended and her own assumption of sensual wickedness.

Borowczyk was the true heir of Bunuel, a church- and censor-baiting satirist, with a glorious (now perhaps frowned upon) eye for the erotic. But even a nodding acquaintance with his work does not prepare the viewer for the unsettling, surreal atmosphere of a film that has been called both polymorphously perverse and interestingly offensive.

5. Diamonds of the Night (Jan Nemec, 1964)

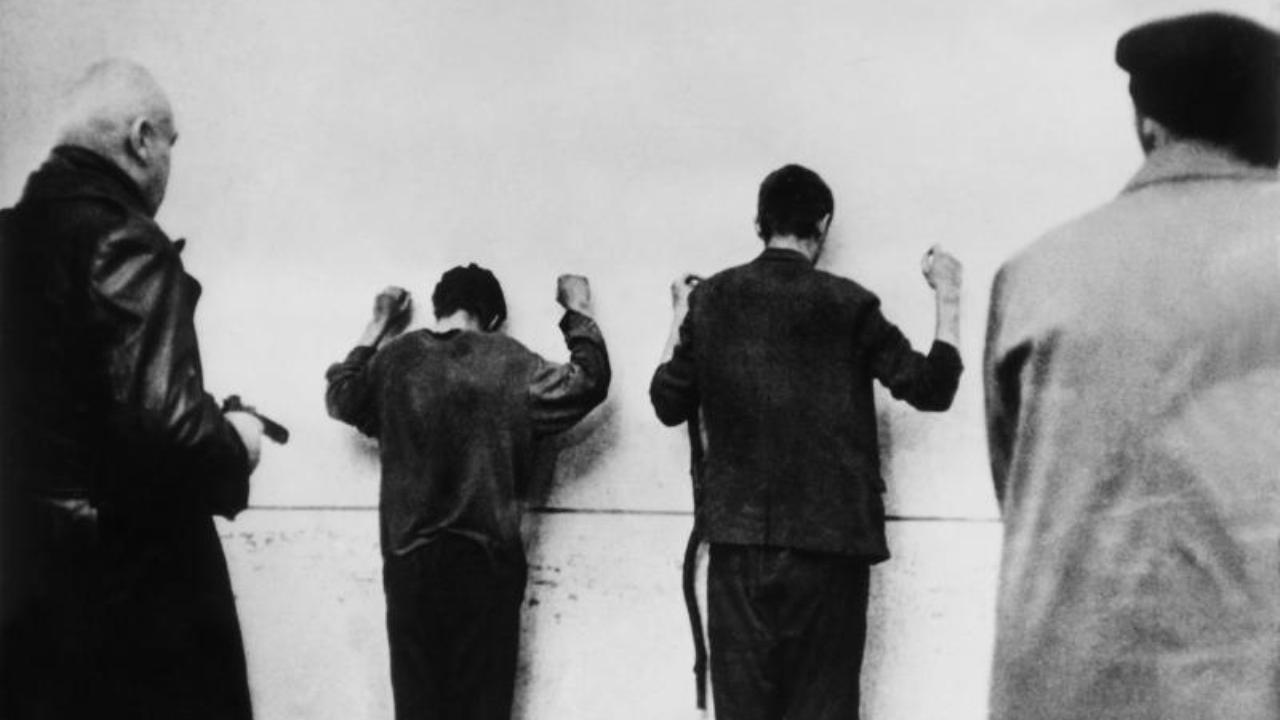

Elsewhere, the 2010s saw the re-emergence not just of individual artists, but of whole pockets of cinema that had lain neglected. Once again, British blu-ray label, Second Run, was at the forefront, releasing film after film from the rich back catalogue of ’60s Eastern European cinema. But the most valuable rediscovery here was of Diamonds of the Night, whose director Jan Nemec tragically died in 2016, two years before the restoration of his remarkable debut was premiered at Cannes. Lasting little over an hour, it documents the flight of two men from a train destined for a concentration camp, and their desperate attempts to survive in the surrounding forest.

Watching it is like unearthing a missing link in the history of cinema; it could be shown to any group of film students as an object lesson in the use of imagery and sound in conveying purely tactile and sensual impressions, those of fear, hunger, despair, longing. The constant flashbacks to the city and their last day of freedom are simultaneously beautiful and distressing, and the cumulative poetic effect has a power comparable to Tarkovsky and Bresson.