5. A Hidden Life (2019)

Director Terrence Malick gives his audiences scenes to behold like few directors today. Along with the adept eye of his cinematographer Jörd Widmer (camera operator on Tree of Life), Malick is reverent to every image that he shoots- be it the utilitarian architecture of a prison, the physicality of farm life, an intimate family moment, or the grandest scenes of rugged, Alpine topography. Somehow this film makes everyday moments possess an almost religious beauty.

We see ample use of natural light, handheld camerawork, and shorter lenses (mostly 12mm). These lenses give viewers expansive, wide-angle shots as well as distorted, yet very intimate close-ups. As a result, what appears onscreen feels more like real life and further enhances the deep emotions of this film. The three-hour running time is deliberately paced, so sit back, soak up the imagery, and feel the unwavering, peaceful message of a dissenter against World War II.

4. I Am Cuba (1964)

After winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes for his 1958 film, The Cranes are Flying, director Mikhail Kalatozov created this experimental, anti-American, propaganda film. Now, if you are asking yourself, “Do I really want to see a Russian propaganda film about Cuba?”, the answer should be “yes”, as you have never seen anything like this! In pre-production during the Cuban Missile Crisis, this was a joint Russian/Cuban co-production with ample resources that facilitated its innovative style. After a poorly received opening in Russia and Cuba, it was pulled from theaters and was all but lost for nearly thirty years until American filmmakers rediscovered and salvaged it from oblivion with assistance from none other than Martin Scorsese and Frances Ford Coppola.

The craft in making this film is evident in every frame’s exposure as is the fluid composition of its cinematographer, Sergei Urusevsky. The ever-moving, handheld camera floats beautifully through most scenes with equally smooth and complex blocking of the actors. The high-contrast, black and white cinematography (and white and black in scenes actually shot with infrared film stock) is so arresting that it will surely make you forget about the propaganda angle and focus on the art.

Most people know and revere the long takes and tracking shots of Orson Welles and Martin Scorsese and now you can add Kalatozov to that list. Without giving too much away, his nimble camera goes from land to sky and even underwater without a cut. Don’t blink! The only way that these long takes could have been made better would have been with a modern-day drone. If you take into account the technology of the day, the smooth, gravity-defying movements of the camera become more and more wondrous to behold. You have to see these shots to truly believe them. If you want to learn more about the history and production of this film, there is a brilliant documentary entitled, I am Cuba: The Siberian Mammoth.

3. Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

After watching this stunning film, you will most likely never look at a birch forest the same way again. This is the first feature film of the legendary, Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. He shows us that he is already a master of the camera, his actors, editing, his script, and expressing emotions through the art of film.

Cinematographer Vadim Yusov deftly captures the beautifully expressive faces of his actors, especially the young Nikolai Burlyayev as Ivan. Ivan’s Childhood shows viewers the ample beauty of nature and humankind as well as the terrors of war. As General Sherman said, “War is hell.” and Tarkovsky wants all who watch Ivan’s Childhood to know it, but also not to forget the fragility of the lives of the people who live through it.

2. The Trial (1962)

While most people know Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, sadly, many would be hard-pressed to name another of his films. One of the ignored treasures of this master of cinema is The Trial. Based on Franz Kafka’s novel by the same name, Welles and his cinematographer Edmond Richard (who would later shoot Welles’ Chimes at Midnight) take us on the journey of Josef K fruitlessly trying to discover what crime he was accused of committing.

None other than Anthony Perkins (of Psycho fame just two years earlier) plays the leading role of a nervous fellow named Josef K who duly feels that the world is against him. Welles also has a juicy role as K’s legal advocate. Kafka often writes about the helplessness felt by people in regards to bureaucracy. While setting this version in a different era than Kafka did, Welles successfully makes his viewers feel beaten down by the system through the crafted combination of his actors’ performances and the mise-en-scene.

Like Kafka’s book, this film opens moodily where Josef K lives. Wonderfully claustrophobic sets with low ceilings photographed by Welles’ low-angled camera clearly create the disturbing tone of what will follow. Later we see more of Welles’ inventive visual style with textbook uses of deep focus, Dutch angles, and rich, black and white cinematography. The look of the world that Josef K inhabits in The Trial is deeply troubling and the power of bureaucracy is never felt more strongly than in the courtroom that is stuffed to the rafters with masses of onlookers casting accusatory looks at our hero.

One of the many scenes that will stay with viewers is when Josef K is chased by dozens of haunted-looking children into the artist Titorelli’s “apartment” while the strains of fast-paced, jazz music blare. Titorelli’s wood-slatted abode resembles a jail cell where, between the boards, the judging and prying eyes of the children can still get at Josef K, while the playful chiaroscuro continues to keep the audience off-kilter. If the original visual style of Citizen Kane piqued your interest in Orson Welles, do not miss The Trial.

1. Que viva Mexico (1931)

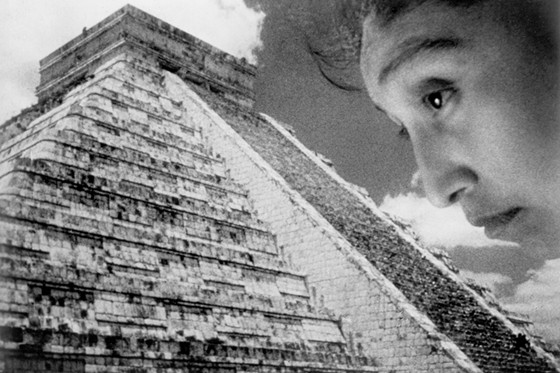

Sergei Eisenstein is known the world over for his films Battleship Potemkin, Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible, but one of his most underseen works, Que viva Mexico, also contains some of the most beautiful and imaginative images ever captured on celluloid. The film was produced by American novelist Upton Sinclair with the help of some other financiers. The saga of its genesis and production is long and complex, but what we are luckily left with today is a dream-like ode to Mexico’s history and culture thanks to the brilliant visionary, Eduard Tisse, who was Eisenstein’s regular cameraman and cinematographer throughout his career.

Surely in the 1930s, the scenes portrayed in the film were seen as exotic to Russians and audiences worldwide. Ancient pyramids tower and palm trees wave in the opening shots while Aztec and Toltec decorative patterns are on full display. One of the most beautiful aspects of this film is how lovingly and artistically the unique faces of the Mexican people are captured. Their high cheekbones, curved noses, sun-darkened skin, and straight, black hair are all beautifully featured. Eisenstein and Tisse shoot these timeless bodies and faces in the most visually striking poses imaginable as if they emerged from the carvings upon the stones that make up those very pyramids. Deep focus, bright sunlight, and inventive framing juxtapose objects and people in the frames to make the ordinary appear extraordinary.

We are shown the time-honored sport of bullfighting as well as the attire, cooking methods, and lifestyles of Mexico. It is truly a historical document where time stands still for audiences of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The film ends with the annual celebration of Día de los Muertos or “Day of the Dead”, where celebrants honor family and friends who have passed on and those who have died are said to symbolically awaken to partake in the celebration. Skeleton puppets and traditional candy skulls fill the screen while children revel in the festivities. Few films bring a nation’s culture and people to the screen as artistically as Que viva Mexico.