After the 1979 revolution in Iran, severe restrictions were imposed on the arts and various cultural institutions. Every film needed to go through a strict screening process and adhere to the Islamic codes of conduct. The New Wave of Iranian cinema had already started a decade before the 1979 revolution; however, after the revolution, the aforementioned restrictions further inspired Iranian filmmakers to explore more abstract concepts that violated no explicit rules.

Certain major filmmakers of the Iranian New Wave (such as Abbas Kiarostami and Sohrab Shahid Saless) had already begun their careers pre-revolution, but Mohsen Makhmalbaf is arguably the most important figure of the New Wave to start his career after the revolution.

Being born into a low-income working class family, Makhmalbaf began working at the age of eight in order to raise money for his family. Later at the age of 17, Makhmalbaf and a few friends planned to attack a police officer in order to steal a gun for their anti-monarchy militia, but instead he was shot and imprisoned. He spent five years as a political prisoner, six months of which he was subjected to torture. In prison he began to write, and he began his film career shortly after his imprisonment.

Based on his experiences with poverty and political activism, his films became a voice for the poverty-stricken lower classes and the politically oppressed. He began his radical expression of distrust for authority, capitalism, and censorship. Though his early films showed a certain Islamic idealism, he re-invented himself with every subsequent film to present his propensity towards experimentation, both in style and in content.

Now, after 26 feature length films, he is one of the most eclectic and eccentric figures of world cinema. Makhmalbaf is a fearless director, a true philosopher who dares to touch on subjects that many have shied away from. He explores the very foundation of cinema and what it takes to produce a film. His cinema explores the inherent struggle of the arts to remain relevant and even useful.

Makhmalbaf’s movies often showcase the deep discomfort of the arts, and even though they are not always perfectly palatable, they always make a statement; sometimes overtly explicit, other times nuanced and subtle.

Throughout his career he has created unforgettable images and paved the way for new discourse. Here’s a list of his 10 most remarkable films that every fan of international cinema should watch.

10. The Peddler (1987)

The only film in this list made before Makhmalbaf made a name for himself in Iranian cinema. “The Peddler” is an anthology of three short films, each of which explores the handicaps of the lower classes from a different angle.

The peddler is a peek into the mind of the working class without the previous heroism associated with such protagonists. Before Makhmalbaf, the working class hero was a common trope, but in “The Peddler,” Makhmalbaf exhibits a disdain for such narratives. The protagonists of “The Peddler” are floundering in social injustice without a clear path to survival.

The first short is about an impoverished couple struggling to abandon their newborn in the middle of the city bazaar, simply to give the child a better life. The second episode is about the mental illness of a young man who has abandoned his life in order to take care of his sick mother. And the third episode is about the socio-political discrimination of Afghan immigrants in Iran.

“The Peddler” is a perfect launchpad for what Makhmalbaf’s films would become in the following decade: raw, political, and edgy.

9. The Actor (1993)

Before “The Actor,” Makhmalbaf chiefly worked with non-actors. He often expresses his interest in zooming in on the lives of ordinary people as opposed to hiring trained actors to fulfil such roles. “The Actor” marked the first time he directed an A-list roster of actors. The protagonist of the film, Akbar Abdi, was a nationally beloved and well-known actor at the time, known mostly for his increasingly comedic and endearing roles.

Much like Alejandro G. Inarritu’s “Birdman,” “The Actor” is inspired by the real-life story of an actor. Abdi plays himself, a popular actor who struggles to break away from being typecast in silly roles and instead aspires to act in arthouse films. He wants to be taken seriously while his mentally deranged wife is overcome by the superstition that marriage (and its logical conclusion, childbirth) is the cure-all for a woman’s existential woes.

“The Actor” explores the purpose and meaning of cinema in the lives of everyday people, the power that celebrities hold over the masses, and the ineptitude of tradition to assist those living with mental illness. This film is one of the only times that Makhmalbaf employed classically trained actors for one of his films.

8. Marriage of the Blessed (1989)

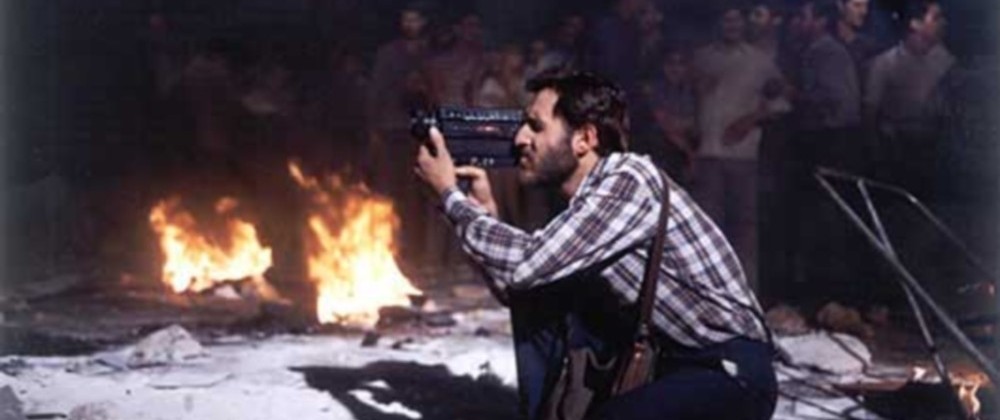

“Marriage of the Blessed” directly addresses the brutality of the Iran-Iraq war, the ethics of portrayal, and the role mass media plays in its exploitation. The main protagonist is a war photographer who gets discharged after surviving a gruesome attack, and the plot follows his struggles to adjust to normal life after witnessing the horrors of war.

“Marriage of the Blessed” is a film about collective grief and how the media can utilize it to fuel wars and sell products. Makhmalbaf floods the film with revolutionary slogans in order to dissect their meaning and the role they play in mobilizing the masses toward an ideal; behind these words are journalists, the click-clack of whose typewriters is often overlapped with the sound of machine gun fire.

“Marriage of the Blessed” is the beginning of one of Makhmalbaf’s trademarks, which is the breaking of the fourth wall by acknowledging the act of filmmaking. As the third act approaches, we follow the protagonist through the slums as he obsessively takes photos of the homeless. The war photographer seeks a new misery to portray, and as the audience begins to question the reality of the footage, we hear police sirens followed by an officer questioning what the crew is doing in darkness.

We hear the word “cut” from the crew, but Makhmalbaf demands the crew continue shooting as he assures the police officer that this is the set of a film shoot. Makhmalbaf acknowledges his need to exploit the imagery of the impoverished and oppressed in order to make his statement about the exploitative aspect of popular media.

7. A Moment of Innocence (1996)

“A Moment of Innocence” is an entire film building up to a single moment; an entire story that culminates in a single image. In the film Makhmalbaf acts as himself, trying to direct a 17-year-old boy to re-enact young Makhmalbaf’s attempt to steal a pistol from a young police officer by stabbing him; and parallel to his storyline, we see the ex-police officer trying to direct a young boy to play the young police officer in the same scene.

The film jumps between scenes that are slated “Re-enacting the Director” and “Re-enacting the Police Officer” as this documentary-style drama weaves in and out of reality. Characters dynamically flow between their fictional and their true selves until the truth of every statement is questioned. By the second half of the film, we no longer know what is real and what is scripted.

The beauty of the film lies in its sincerity, its delicate storytelling through the smallest details, and its constant reinvention of its own narrative. What we believe to be true in one scene is shown to be scripted in the next, and we’re constantly given a new perspective on a simple event being re-enacted over and over again until we begin to question what we know about the narrative.

This is a film that is truly about a single moment, captured in its breathtaking final image.

6. The Cyclist (1989)

The first movie that made a name for Makhmalbaf. A close-up of the hardships of Afghan immigrants in diaspora in truly neo-realist fashion, “The Cyclist” is a display of poverty as spectacle. The titular cyclist is an Afghan immigrant with a sick wife, whose hospitalization completely paralyzes her family financially. Seeing no other way to proceed, the protagonist Nasim (Moharram Zainalzadeh) accepts a deal with a local hustler who says he’ll pay Nasim’s hospital bills if he cycles around the town square day and night for seven full days.

“The Cyclist” is one of the first films to ever speak of the hardships that Afghan immigrants endure living as second-class citizens and low-wage workers in Iran, while simultaneously criticizing how the media treats their misfortune as a form of poverty tourism.

As Nasim keeps cycling around the town square, there are bets made on his survival, and several groups do everything in their power to influence the endurance of Nasim in a way that favors them financially.

One of the film’s most memorable scenes is when Nasim uses matchsticks to keep his eyelids from slamming shut in exhaustion. “The Cyclist” is a delicately powerful and fearlessly human film by Makhmalbaf.