5. The Sorrow and the Pity (1969, Marcel Ophuls)

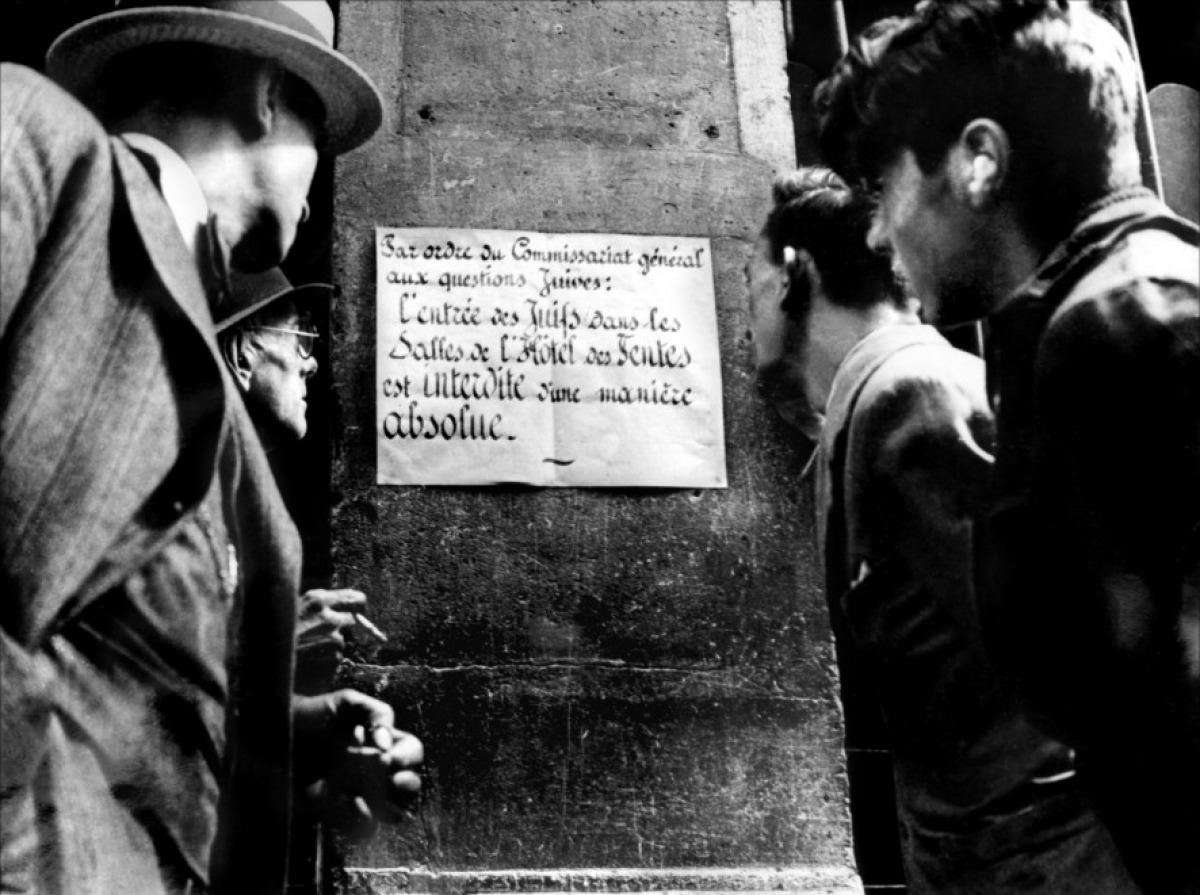

An obsession of Alvy Singer in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, The Sorrow and the Pity may catch the attention of some cinephiles. The geographic focus of the film, Clermont-Ferrand, is also home to the first international short film festival. Before it became a part of film culture, however, the city of Clermont-Ferrand was the center of French maquis resistance under the Vichy regime, Nazi Germany’s main independent ally during World War II. The Sorrow and the Pity, a four-and-a-half hour long documentary, outlines the various rationales of the people of Clermont-Ferrand who collaborated with, resisted against, or simply went along with this regime.

The film exists in a two-part historical exploration: The first – entitled “The Collapse” – predominantly focuses on an interview with Pierre Mendès France, a future prime minister of France who was jailed by the Vichy regime for joining the Resistance. The second – entitled “The Choice” – centers on Mendès France’s foil, Christian de la Mazièrethe, a French aristocrat who joined the Nazis on the battlefield. Throughout the film, Ophuls interweaves interviews with contemporary newsreels and archival footage from World War II in a way that captivates the viewer and makes the long runtime of the documentary feel like a fast-paced drama.

The main feat of The Sorrow and the Pity is that it completely flips the table on traditional thinking and reveals that France has been covering up some painful historical facts with an idealized collective memory of its occupation. Ophuls’s “revisionist” history discloses that bureaucratic apathy and rationalized collaboration, not resistance, were the predominant features of Vichy France.

The fact that most of the interviewees in the film appear to be seemingly ordinary people makes their avoidance of moral discussions and casual reasonings for their collaboration all the more unforgettable. Nonetheless, Ophuls skillfully evades making any definitive ethical judgement on the individuals and compels the audience to consider whether their actions would differ in such a situation.

4. Europa Europa (1990, Agnieszka Holland)

More of an epic odyssey throughout the entire history of World War II than a pure Holocaust film, Polish director Agnieszka Holland’s war drama Europa Europa takes the viewer on a journey, sparked by the infamous pogrom known as Kristallnacht, through the eyes of Solomon Perel. This true story follows the German-Jewish boy as he travels from Nazi Germany to Poland to the Soviet Union, which then becomes occupied by the Nazis, and then back to Nazi Germany, which is finally liberated by the Soviets.

An incredible story of survival that one would find absolutely absurd if it was not true, Europa Europa details Perel’s escape from Nazi imprisonment in the best way he can imagine – getting as close to the enemy as possible. Perel attempts to hide his identity and disguise himself as an Aryan Nazi in order to avoid the fate that the rest of his family and the vast majority of European Jews faced at this time. While Perel is able to do so almost to no fault, one aspect continues to haunt him: his circumcision, which acts as a permanent physical mark of his Jewishness.

Holland’s objectivity throughout Europa Europa is refreshing, and her ability to intertwine romance – most notably in the form of Perel’s German love interest played by Julie Delpy (pleasing any Linklater fans out there) – with humor and horror is artful. Perhaps the most captivating scene in the whole film and a prime example of Holland’s twisted humor occurs when a teacher selects Perel out of a class of Nazi Youth and measures his head with calipers to illustrate that he has perfect Arayan features.

At the end of the film, the viewer gets a glimpse of the real Solomon Perel, who – to this day – seems astonished by his survival. It is a must see film not only to see Perel’s luck run its course, but also to explore how our understanding of identity fares under the most extreme of circumstances.

3. The Pianist (2002, Roman Polański)

There is only one way to describe The Pianist: a harrowing masterpiece. In the film, Polański tells the true story of Polish-Jewish concert pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman and his survival of the German occupation of Warsaw.

Like Europa Europa, The Pianist is a tale of survival; however, unlike Perel, who becomes one with the enemy in order to avoid detection, Szpilman’s story is one of escape and hiding. Szpilman leverages his fame for personal advantages in the Warsaw ghetto and later bunkers down in safe apartments while most of the Jews are taken to death camps.

Because the film follows a man in hiding, The Pianist is slow-paced, taking advantage of Adrien Brody’s physicality and subtle performance, which often relies on long silences, letting his face simply convey all the emotion one can imagine is humanly possible to feel. It is, thus, no question why this film made Brody the youngest recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Because the film never delves into the Nazi death camps (since Szpilman was able to avoid such a fate), one might think The Pianist does not contain the visually horrific sights of other Holocaust films. On the contrary, Polański manages to depict some of the most graphic and unbearably distressing scenes of the evils produced by man by making them both personal and specific. He also tastefully avoids cheap drama and sentiment, making the horrors all the more real and adding to the film’s gravitas.

By foregoing romanization and Hollywood cliches, the film is able to create an intimate feeling with its viewers. While this intimacy has its tradeoffs, namely forcing the film to ignore certain aspects of the Holocaust, it pays off by allowing the audience to fully connect with one man’s story. At its close, The Pianist considers the realm of survival guilt and the limits of humanity in a way that might haunt you – but there are good reasons for these lingering effects.

2. Au revoir les enfants (1987, Louis Malle)

A young, wealthy schoolboy at a Roman Catholic boarding school in occupied France seems like an unlikely star for any movie about the Holocaust, yet it is exactly this innocent, childlike perspective that makes Louis Malle’s autobiographical film Au revoir les enfants (“Goodbye, Children”) so affecting. The film in its entirety creates a sense of realization – a realization that evil can abruptly appear out of nowhere, toppling our understanding of the world, and a realization that even our smallest actions can have the most dire of consequences.

Malle’s cinematic double is French schoolboy Julien, who eventually befriends a fellow misfit, Jean, when Jean and two other boys are welcomed to the school midyear. What Julien doesn’t know is that the newcomers are all Jewish, and the school’s headmaster, Father Père Jean, is providing them refuge from the Nazi regime. In fact, it is unclear whether Julien ever fully comprehends Jean’s identity or the weight that it carries until, perhaps, the end of the film when the Gestapo raid the school and Julien unintentionally outs his fellow classmates with the smallest of glances.

By focusing on the daily life and routine of the boarding school, Malle creates a no-frills film that avoids the dramatic and contains a relatively simple plot. As a result, he pulls the audience into a very specific and controlled world, making it all the more unsettling when this environment changes by the encroaching horrors of the Holocaust. Au revoir les enfants also shows how utterly confusing the racist acts – from the subtle to the overtly violent – are for these children by maintaining Julien’s innocence and unawareness throughout the film.

It’s possible Malle made Au revoir les enfants because he still identifies with little Julien, not knowing how to feel about the horrors he witnessed. No matter the reasoning, Malle presents a host of unanswerable questions as he paints a vignette of friendship and childhood. Should Julien feel guilty? Does he even know what he did? Why were the Nazis looking for Father Père Jean and the boys? This masterful cinematic work forces the audience into the disconcertment one might expect to experience in such a history-altering time.

1. Shoah (1985, Claude Lanzmann)

No list about the cinematic representations of the Holocaust would be complete without Claude Lanzmann’s epic ten-hour long documentary Shoah, and it deserves no place on this list other than the number one spot. There is, in fact, nothing that can be said about Shoah, which means “calamity” in its original Hebrew, other than that it is a necessity in preserving the memory of the Holocaust.

Lanzmann, a French filmmaker and the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, took eleven years to release his documentary, which features interviews from victims, bystanders, and perpetrators of the Holocaust. The film contains no voiceovers and no archival footage as it travels throughout the Chelmno extermination camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and the Warsaw Ghetto. In this way, Shoah allows the history of the Holocaust to be completely told from the perspective of those who lived it, making the documentary more like a witness testimony than a film.

While the length of Lanzmann’s film may appear daunting, it only serves to pull the audience in deeper into the horrors of the Holocaust and make them feel – if at all possible – like they are also witnessing the heartbreaking sights described by the interviewees.

Next time you find yourself with ten hours to spare, don’t hesitate to watch Lanzmann’s Shoah. Spending ten hours to watch this masterpiece is nothing compared to the time Lanzmann took to put it together.