There is a natural tension to the open road, with its isolation broken only by a complete stranger piloting their own ton or two of steel, glass and rubber where only suckers heed the speed limits. Most of the world might be carved up by roads, but that doesn’t mean that civilization grew up alongside them. It’s still a frontier, with plenty unknown on either side of the asphalt. Here are ten terrific pictures about why that cancelled road trip might be a blessing in disguise.

1. The Hitcher (1986)

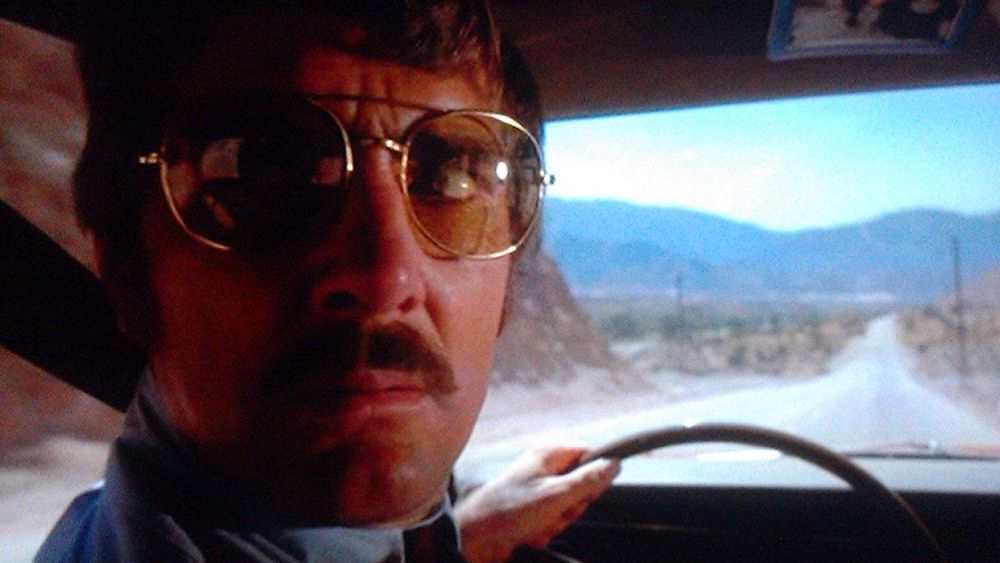

When The Hitcher was first released, it proved a modest commercial success, largely ignored or reviled by critics. It grew in stature as HBO played it incessantly, and now it routinely shows up on the lists like this one. The premise couldn’t be more basic, as a young man (C. Thomas Howell) drives cross country to deliver a car from Chicago to San Diego and on one dark and stormy night, picks up a hitchhiker (Rutger Hauer). The script operates like those great seventy-minute B-movies of the thirties and forties, wasting no time with back stories or set-ups. Howell picks up Hauer in the opening moments and minutes later, Hauer calmly explains he’s going to kill this good Samaritan.

The script manages to keep its foot on the gas for the rest of the movie, finding clever ways to leap to where other movies like this might end, and pressing on to more unexpected, and depraved terrain. Jennifer Jason Leigh does her best to elevate her roadside waitress into someone more interesting and nearly pulls this off. But this is Hauer’s movie, and rarely has an actor seemed to delight as much in playing an apex predator. The movie wisely subscribes to the Michael Myers school of character development for its antagonist, understanding that childhood trauma and rationales only make monsters in such movies less intimidating.

Howell makes for a fine everyman here, though stumbles when the movie needs him to process his trauma is more disturbing ways. Richard Harmon directs this with competence and care, benefiting from an era where he got to blow up real cars, so the chases and crashes have a weight missing from contemporary movies that aren’t Fury Road. It’s a satisfying little thriller, but its screenwriter Eric Red would go on to produce far more intriguing genre experiments, writing both Near Dark and Blue Steel for Kathryn Bigelow. And unfortunately, Hauer would never get the chance to bare his teeth like this again.

2. Joyride (2002)

Before JJ Abrams became the anointed remixer of juggernaut franchises, he co-wrote this nifty B movie with Clay Tarver about a trio of young folks who play a nasty prank on a truck driver using an old CB radio. It earned some respectable reviews and its money back, but like a few others on this list, its reputation only grew over time.

Here Paul Walker offers to drive his college crush (Leelee Sobieski) home, with his clownish pal (Steve Zahn) along for the ride. By this movie, Zahn perfected his persona as a destructive, if well-meaning, moron. Zahn’s prank fuels the story and builds organically, never lurching into outright cruelty, but hurtful enough that the wrong person would take it very, very personally, which a truck driver with the CB handle of Rusty Nail (sumptuously voiced by Ted Levine) most certainly does. The twists are small but satisfying, refusing to take the big plot swings that made JJ’s company Bad Robot so famous for intriguing premises, jaw-dropping second acts, and deeply flawed endings.

The movie’s secret weapon is oddly enough the director, who quietly built his name on a string of accomplished neo-noirs in the nineties like Red Rock West and The Last Seduction. John Dahl balances the tone well, keeping this a high-grade thriller with nasty streak, as opposed to a more overt horror play, that might strip the plot down to a grocery list of kills. Rusty Nail and this trio are well-matched the whole way through, with an ending that can still produce shivers after repeat viewings. It’s exactly the type of thriller that people shrug off as simple, when in fact it’s a high-wire walk few pull off.

3. Breakdown (1997)

The generic title didn’t do this movie any favors, but it still became a small bore hit on its release, reminding everyone why its lead, Kurt Russell, has been a star for decades. The movie opens with Russell in a near collision with a truck driver, followed by a brief argument at a gas station, only to find his car breaking down in the middle of nowhere. He lets his wife hitch a ride with another trucker to get help, and naturally, she disappears into thin air. What follows is hardly groundbreaking, but the tension swells with rock solid story logic that too few of these movies ever bother to employ.

This was the directorial debut for Jonathan Mostow, who has the reliable chops that would have made him the second coming of Don Siegel or Robert Aldrich given enough time cranking out movies like this. Hardly a revelatory stylist, Mostow knows what he has in Russell and his script, and isn’t afraid to let those things shine here. But he shows a gift for sharing narrative information visually and letting the audience add two and two for themselves, as at one point, he unveils the time and scope of the conspiracy at work in a single image.

Still, this movie relies on Russell to deliver the goods, and he does, as he’s a delight to watch get frustrated, lose his cool, regain it, all with his average Joe aplomb. Few actors can play exasperated without ever falling into self-pity as Russel does so naturally. He’s just doing the best he can and looking for a break that is long overdue. This is stellar middlebrow entertainment, of the kind that shouldn’t make that an insult.

4. Detour (1946)

Long heralded as one of great no-budget noirs of the 1940s, Detour is a miracle for more than its financial constraints. Its director Edward G. Ulmer managed to stitch together his movies with used sets, hungry actors and a few, very few, well-placed lights. In this one, a down on his luck piano player (Tom Neal) hitches a ride with a bookie (Edmund MacDonald) to California to meet up with his girlfriend in Hollywood. Along the way the bookie ends up dying in an accident no one would believe happened. Too nervous to trust the police, Neal assumes the bookie’s identity and if his luck wasn’t already circling the drain, it’s flushed away upon picking up the one hitchhiker (Ann Savage) that knows that bookie.

Savage swiftly blackmails Neal, assuming exactly the kind of foul play the cops would. She’s not a garish femme fatale though, looking to gobble him up whole. She’s a fragile, broken soul that believes the only way to get what she needs is to harass, cajole and snatch it from the world around her. And Neal, desperate to put the detour behind him tries to escape her any way he can.

Now an established classic, Detour has the strange luxury of looking better now than it did in 1945. A recent 4K restoration has turned its glaring whites into a hypnotic glow, and its blacks into velvet shadows. Its longevity can’t be credited only to its place as an early noir, but rather, what kind of noir it is. Yes, the genre is built around bad, mostly criminal decisions, but the best have an aura of inevitability. It’s not simply a matter of falling for the wrong girl or aiming for the quick fix, but of trying to do the best with bad circumstances only to sink even deeper into trouble. Neal didn’t want anything but to reunite with the love of his life and yet, the open road had other plans.

5. The Vanishing (1988)

Stanley Kubrick once called this French-Dutch thriller the scariest movie he’d ever seen, and reached out to its director George Sluizer, to discuss how he edited it. This makes sense given that the suspense is built on the need to know, which had to resonate with Kubrick, a man who clearly had a ravenous curiosity.

It begins with a haunting rehearsal of the crime to come, as a pair of lovers, played by Gene Bervoets and Johanna ter Steege are separated when their car breaks down, only to be swiftly reunited. But then at a crowded rest stop, she goes to the bathroom and never returns. Bervoets waits and waits, but there is simply no sign of her, though some workers saw her with another man, implying that she might have simply left her boyfriend behind. This is a movie, so that’s clearly not the case, and soon The Vanishing splits its POV, following the killer (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu) as he plots the kidnapping, and Bervoets as he devotes his life to finding out what happened.

As it turns out, Donnadieu is a sweet family man and chemistry professor whose sociopathic tendencies are bundled up as tight as those in a 19th century Russian novel, intellectualized until it’s a bloodless act within an indifferent universe, until it’s not. As Bervoets unravels from his grief, Donnadieu only grows in calm and power, sending him post cards inviting him to meet, only to stand him up over and over again. Truly great horror filmmakers require an expansive understanding of the human condition to avoid relying on crude sadism and genre clichés alone. And here, the shocking finale arrives when the lead can’t resist the urge to know, and credibly becomes a willing ally in the killer’s larger design.