The great outdoors makes for a formidable antagonist: unthinking, relentless and only more intimidating as people live more of their lives through screens. It also allows for inherently cinematic stories that can be told wordlessly for long stretches of time, relying on the actors to register everything in their faces. The stakes stay high, and the plots streamlined, if the filmmakers can resist the urge to flashback to some backstory that only interrupts the tension. When someone’s running out of food or trying to avoid being eaten by a bear, their lousy marriage doesn’t seem so crucial anymore, unless, of course, some savvy filmmakers find a way to make it matter.

Here are ten thrillers that make audiences grateful for a roof, running water, and yes, even the screen where this appears.

1. The Flight of the Phoenix (Robert Aldrich, 1965)

By 1965, Jimmy Stewart had long since shed his ever chipper, cornpone ways by giving dark, obsessive performances for Anthony Mann and Alfred Hitchcock in the fifties. And here we find those unsavory shades fully integrated into his lead performance here as a pilot that crashes in the Libyan desert due to a sandstorm, leaving an all-star cast to run out of water and slowly go crazy. That is, until one passenger turns out to be an airplane designer who thinks they can build a new plane from the old one, and fly out.

The movie feels like a precursor to the disaster pictures of the seventies, with the likes of George Kennedy, Peter Finch, Ernest Borgnine, Dan Duryea and Richard Attenborough bickering and falling apart in the sand. Aldrich relies on some cliched music cues and lets the pace get shaggy as the picture runs well over two hours, but it remains something more compelling than The Towering Inferno or any entry of the Airport franchise. And that’s because as hard as it may sound to build a second plane in the middle of the Sahara, it’s impossible for a group of men to do that when they can’t set aside their egos.

Stewart’s pilot might be riddled by guilt for the crash, but he’s still quick to mock anyone else’s plan to get home. Finch plays a stuffy British soldier who only has faith in standard practices, and that airplane designer is German, who “probably” wasn’t a Nazi, but certainly becomes a petty dictator along the way. And everyone mistrusts the German’s scientific expertise to their own peril, which resonates a bit too much at the moment. Yet, for as much as it meanders, the character development pays off, and each twist hooks the audience right back into place. And by the time that new plane is about to take off, there’s little doubt that no matter what happens, each of them deserve to get home.

2. Hell in the Pacific (John Boorman, 1968)

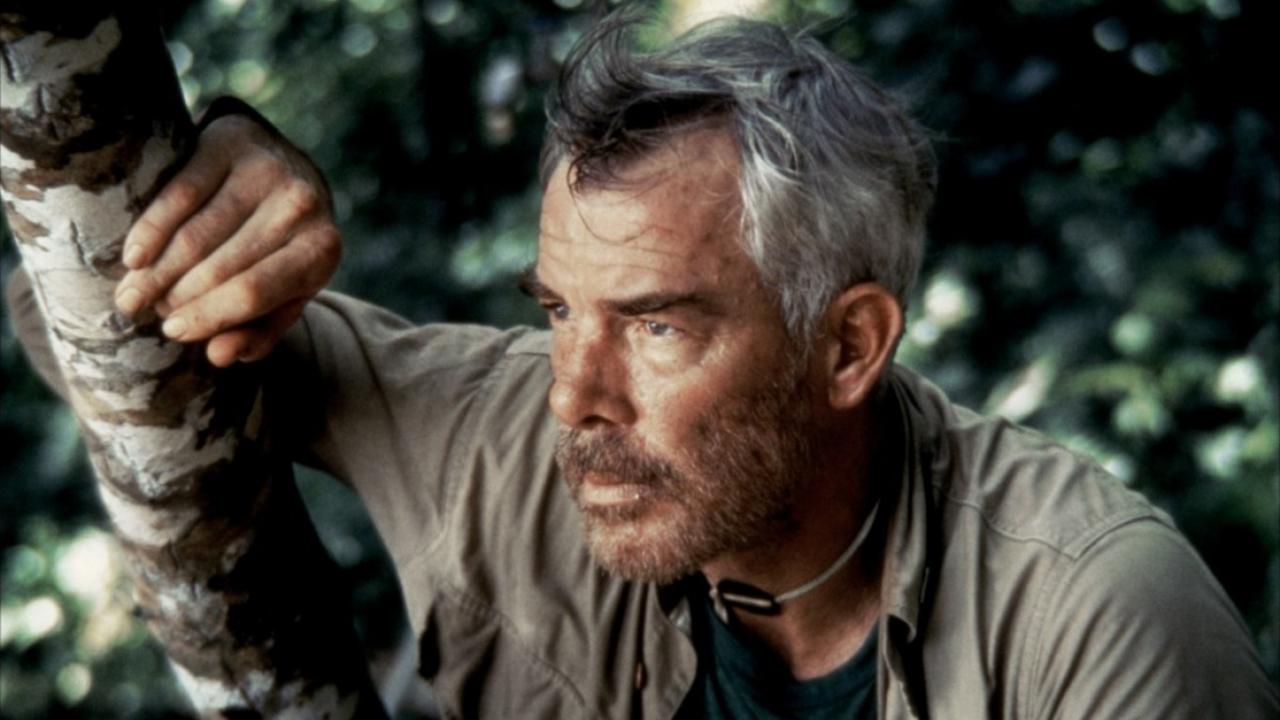

Within the first five minutes, anyone can guess where this movie is going. It’s WWII and an American pilot (Lee Marvin) crashes on a same remote island where a Japanese naval officer (Toshiro Mifune) is already stranded. Of course, they will eventually overcome their differences and work together to get home. But the movie’s lingering power comes from how slowly it takes them to get there, and just how fragile their truce proves to be.

Boorman had just delivered the gleaming crime haiku of Point Blank, and this is no less stylistically adventurous, with Sergio Leone close ups and crash zooms, perspective tricks and a stunning score by Lalo Schifrin that uses everything from natural sounds to church organs. Marvin and Mifune were both decorated soldiers for their countries during WWII, and Boorman knew the shoot might trigger the worst memories from Marvin. It was a troubled production, with Boorman nearly fired at one point, only to be saved by Mifune, which was surprising given that the Japanese star despised taking orders from him.

The result was Mifune’s most sophisticated performance in an English language film, as most American filmmakers only tapped him for his gunpowder scowl and guttural shouting. Mifune speaks without subtitles here, allowing the audience to feel as alienated and confused as Marvin is on the island. Both stars offer equally layered, cagey turns that seem to simmer with their ghosts, and while the movie flopped, it’s lodged as a career high for Marvin and Mifune. Boorman would recover from this with an unlikely hit in the exact same subgenre.

3. Deliverance (John Boorman, 1972)

No list of this kind can ignore Boorman’s masterpiece of wilderness terror, made from John Dickey’s novel about a group of guys having the worst rafting trip in history. Deliverance is so much more than the scene that remains seared into zeitgeist to this day, but after being referenced for the nearly fifty years, the actual movie gets lost. Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds, Ronny Cox and Ned Beatty play old pals rafting through the Georgia backwoods, until they piss off some craven locals who are looking for a terrible kind of fun.

The shoot was an arduous one for all involved, with the actors doing their own stunts on cliffs and in the water, and the DP, Vilmos Zsigmond, working up to his neck in a bitterly cold river to keep water splashing the bottom of the frame. In spite of that backstage trauma, it’s a remarkably reserved picture, and Boorman’s poker-faced, utterly frank depiction of the atrocities make them all the more terrifying. There’s none of the excess gore and melodrama to give audiences some distance from the proceedings. The movie smartly hints at rifts among the men, not so big to make it odd that they’d vacation together, but real enough to bloom into hostility during a crisis. Reynolds never topped his performance here, using his star wattage to show the limitations of unadulterated machismo.

Much is made of Deliverance as a meditation on masculinity, at a time when the sexual revolution was interrogating it, but that’s always felt like too broad a reading. It seems more a nightmare of pampered men who want to play tough on the weekend, only to realize that they really are soft and coddled boys, who left hard labor, and the physical competence that comes with it, to someone else. What makes this such an enduring nightmare is that it shows the wilderness to be not some unsullied Eden, or romantic playground, but a place that destroys pretensions of competence or virtue, both of which Americans tend to revere more than the real thing.

4. Rescue Dawn (Werner Herzog, 2006)

Much of Herzog’s entire filmography could be defined as battles with nature, both in subject matter and the actual shoots. His status as meme engine now only solidifies the idea of the dead-eyed German reminding us how little the natural world cares if anything, or anyone, lives or dies. It also cheapens one of the richest, and most singular bodies of the work by any director. Rescue Dawn is a case in point. Far from some dour meditation, the movie is a high-spirited adventure picture about Dieter Dangler, a German-American POW in Vietnam that Herzog profiled in a documentary back in 1997.

Christian Bale stars as Dieter, and the movie is regrettably best known for a scene where he eats maggots, which true to his method, Bale actually did. But this obscures the fact that Dieter is one of the most hopeful characters in any movie in recent memory, keeping the spirits of his fellow POWs up after crashing in Vietnam, and being captured. He is always plotting his escape and his thick German accent gives a nice comic touch to that unbroken spirit. Herzog mines this upbeat fellow for plenty of laughs, as to find joy as a POW may require a unique brand of mental illness.

This isn’t to say that Herzog doesn’t test that good cheer with some truly terrible suffering, but that unshakable spirit plays like a long-lost American character, before the country devolved into petty adolescents that meltdown when a coffee order goes south. It might have been a hit released in the eighties, but such smart adventure pictures were relegated to the arthouse by 2006, where few people saw it. But it remains one of Herzog’s most accessible and entertaining pictures while staying on brand. After all, the jungle didn’t care if Dieter got out of alive, but Dieter certainly did, and proved resourceful enough to give that jungle a run for its money.

5. Arctic (Joe Penna, 2018)

This austere Icelandic survival picture starts well after our lead, (Mads Mikkelsen) has crashed in the Arctic Circle. We watch his daily routine of fishing and SOS signals until a helicopter flies into view. But the winds are too much, and the chopper crashes, killing the pilot and wounding the other passenger (María Thelma Smáradóttir), leaving Mikkelsen to tend her wounds as best he can.

Low on supplies and aware that Smáradóttir needs real medical help, he rigs a sled to pull her to a care station many miles away. The director understands how to shoot the mountains as an apocalyptic hellscape with off-kilter frames he sits on long enough to let our own imagination make something malevolent out of them. To Penna’s credit, he keeps the proceedings nailed down to credible twists of fate, and isn’t scared to enrich the sense of isolation with long stretches of silence.

That patience and rigor imbues the slightest gesture from Mikkelsen with weight, and the actor radiates a quiet decency that wasn’t evident in his Stateside persona of unsavory European nihilists. Instead, he excels as an everyman and Penna knows that his situation is dire enough that he already has our sympathy, and his choice to save Smáradóttir does the rest, without witty banter or some forced romantic chemistry between the only two characters here. So spartan a style also accomplishes something vital: we’re left guessing until the very last moment if he and his patient ever get rescued, because this movie might be brutal enough to leave them out in the cold.