17. Blue Valentine (2010), directed by Derek Cianfrance

Derek Cianfrance’s anti-romance stars Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams as a couple six years into a dying marriage that is about to extinguish entirely. The actors also play versions of their characters at and around the time when they met. It’s a film in which the little details are everything as it catalogs the moments that, together, weave a portrait of a doomed relationship from birth to decay.

Blue Valentine doesn’t feel like a movie, but rather the (gorgeously shot) recordings of two regular (though damaged) people as they give up on each other and surrender to the nameless void slowly surrounding them. It haunts because it’s about the death of hope, and there is nothing more haunting than that.

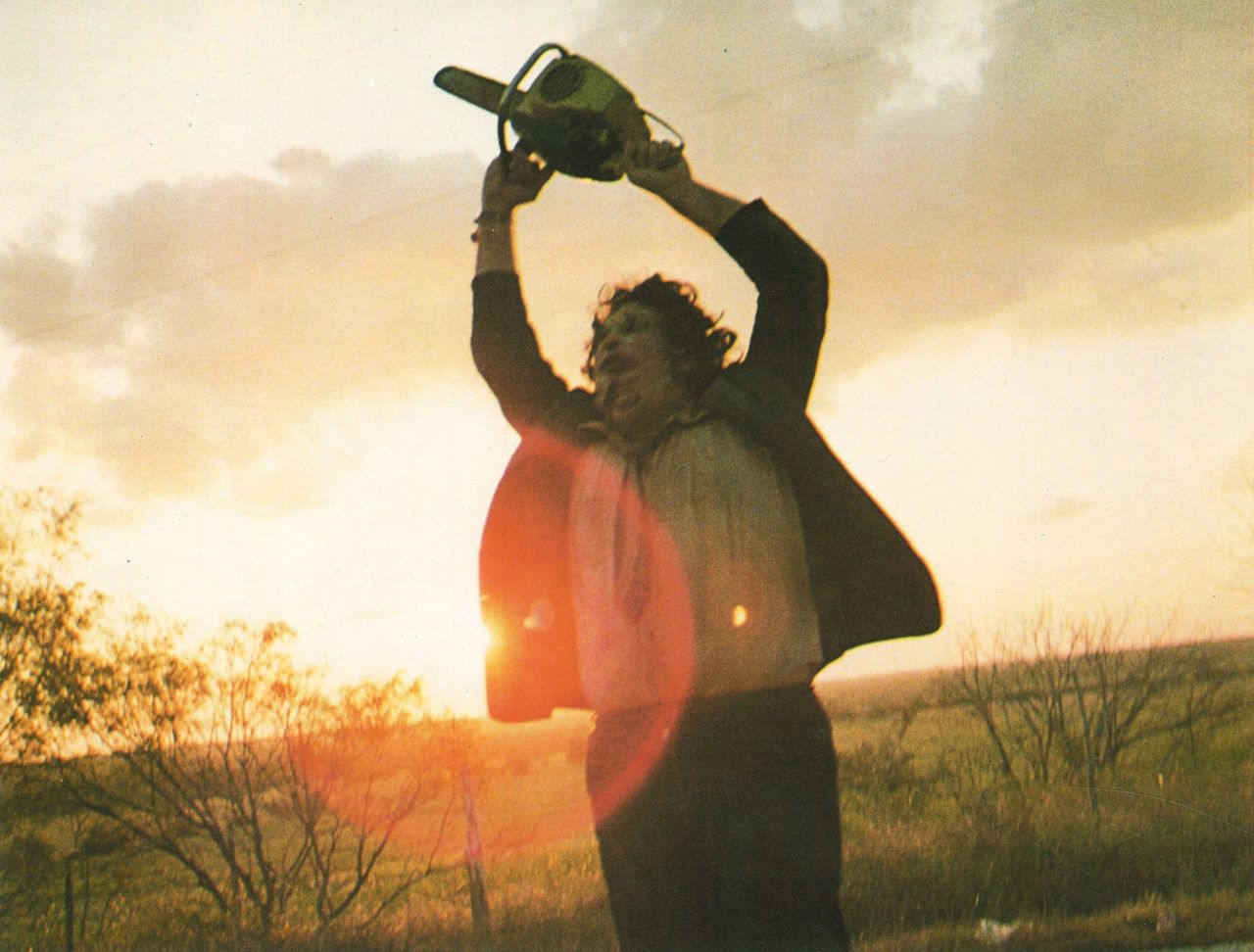

16. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), directed by Tobe Hooper

Few film titles evoke the horror genre quite like this one, and few, if any, struck fear into the hearts of a generation so completely that the title has become a synonym for fear itself. Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece gave form to the anxieties of young people following the Vietnam War and the dark vision of a new America it exposed. The film featured the first masked serial killer in American cinema, sagely anticipating (and in no small part helping to spawn) the rise of the slasher genre four years later with John Carpenter’s masterful Halloween (though the slasher was born here in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Canada’s Black Christmas directed by Bob Clark, both released in 1974).

The “Texas” in the film’s title is key to understanding Hooper’s intentions. To him the film was a personal comedy of sorts about an extremely dysfunctional red state family whose jobs at the local slaughterhouse are being made obsolete by technological innovations, and how this family takes its rage and anxiety out on outsiders—specifically young, college-educated, likely left-wing outsiders. That the developmentally disabled brothers struggle for the approval of a toxic patriarch reflects the personal intimacy of the film even more. As Hooper said when discussing the movie in an interview with The New York Times’ Jason Zinoman about his Austin, Texas upbringing: “Those family dinners can go very wrong… I saw some things growing up that were bizarre and wrong.”

15. Don’t Look Now (1973), directed by Nicolas Roeg

Nicholas Roeg’s supernatural study in grief is one of the seminal films of the ’70s and a landmark horror. Following the drowning of their daughter, John and Laura Baxter attempt to rebuild their lives some months later. But it’s early days, and while Laura attempts to process her grief, John absolutely refuses to deal with it. So it seems a strange and particularly self-flagellating decision when John accepts a job in Venice, the Italian city almost submerged in water where there are no roads, only canals. There, John becomes haunted by a figure wearing the same raincoat his daughter drowned in, a figure he believes is the ghost of his daughter, which darts around the city, always just out of reach, taunting him.

Don’t Look Now’s most haunting element, though, is not one of horror but gritty realism in one of the (in the ’70s, at least) most notoriously vivid sex scenes in cinema in which Laura and John have sex passionlessly, going through the motions like a pair of machines, their grief at the loss of their child having sucked the life from their shared existence.

14. Hostel (2005), directed by Eli Roth

Dismissed unfairly by critics as sadistic and tasteless and, when the term was coined later, “torture porn,” Eli Roth’s Hostel is a clever riff on the xenophobia of post-911 America, acutely aware of the public’s growing awareness and discomfort of an administration that openly used torture as a weapon against its enemies, which had been proven by shocking images of tortured prisoners distributed nationwide by the media.

Violence was in the atmosphere and Roth’s excessive genre exercise smeared it all over the screen, putting a face to the public’s fears. What’s most haunting about Hostel, though, is the realization it provokes that there are people in this world who will pay large sums of money to torture people—and what will be bought will always be sold.

13. The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2008), directed by Mark Herman

Perhaps the only thing more haunting than the horror of the Holocaust is to imagine it through the eyes of a child. Because racism is learned, not inherent, and only through a child’s eyes could the senseless insanity of genocide be most fully expressed. To little Bruno, who lives beside the concentration camp where his Nazi officer father works, the prisoners’ uniforms are pyjamas. Bruno doesn’t understand why his friend, a little Jewish boy called Shmuel on the other side of the fence, is always wearing pyjamas along with everyone around him.

Based on the novel by John Boyne, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas reaches its most haunting point during the climax when Bruno gets his own set of “pyjamas” and crawls under the fence to be with Shmuel, and history follows its course. By the end of the film the cleverness of framing the story through the eyes of a child is clear.

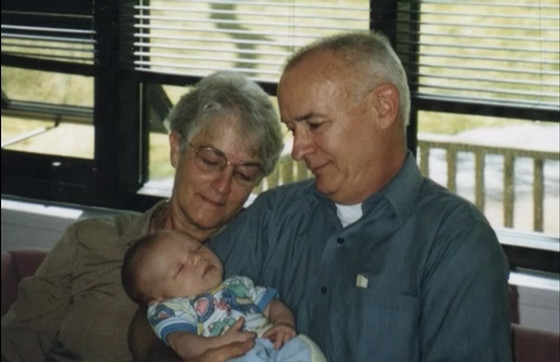

12. Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son about His Father (2008), directed by Kurt Kuenne

The less said about this one the better, as it contains more big reveals than a magic show. It begins as a true crime documentary exploring the murder of Dr. Andrew Bagby, who was shot and killed by the soon-to-be mother of his child—a woman named Shirley Turner who haunts this shattered family, and particularly Bagby’s parents, like a specter of death. The title of the documentary comes from Bagby’s parents’ wish to create a record of Bagby as the father his son Zachary would never meet, to show to Zachary when he grows up.

It’s the film’s later revelations that are so deeply haunting, as well as the desperate grief of Bagby’s parents coupled with the extraordinary love they have for their grandchild. If this one doesn’t extract a tear from you, nothing will.

11. Prisoners (2013), directed by Denis Villeneuve

The most haunting moment of this powerhouse kidnap thriller by French-Canadian director Denis Villeneuve comes at the beginning when two families leisurely socializing inside a nice home on a quiet street in small-town American suburbia come to realize that their two little girls are missing.

The urgency that takes hold of Hugh Jackman’s character as this realization dawns mirrors the film’s sudden surge in energy that doesn’t let up until the credits roll. With clever themes of God-fearing U.S.A. and the War on Terror, ensemble powerhouse cast including Jake Gyllenhaal and Terrence Howard, and twisty, morally grey script, rarely are Hollywood thrillers so complex and haunting.

10. Amour (2012), directed by Michael Haneke

Sorry to break this to you, but you’re going to die. We all are; it’s the only certainty of our existence. Amour, winner of Cannes Film Festival’s prestigious Palme d’Or in 2012, deals with this fact explicitly. It concerns the relationship between an elderly man and woman following the woman’s stroke and subsequent decline into dementia which renders her childlike and helpless and increasingly unlike the woman her husband had known and loved.

Marking a departure for director Michael Haneke, and portrayed with absolute sincerity and without sentimentality, Amour is about the greatest journey we must all finally embark upon, and how true love is marked not by the exciting moments of its beginning but in the compassion of doing what must be done for the ones we love in their final days.

9. Requiem for a Dream (2000), directed by Darren Aronofsky

If 1996’s Trainspotting is about escaping the mundanity of life, 2000’s Requiem for a Dream is about having lost it completely. As seen with his aforementioned The Wrestler, Darron Aronofsky is adept at crafting unsentimental dramas of staggering emotional power.

His landmark Requiem for a Dream launched into the new millennium with an unflinching portrayal of the bottomless depths of dependency addiction forces upon its afflicted, leading them to do whatever it takes to silence the demons for just a little bit longer. Aronofsky’s inventive camera and editing techniques and Hitchcockian fascination with the camera as narrative tool—implying the perspectives of his characters through what is visible and omitted onscreen—greatly accentuate the effect of his haunting, hopeless masterpiece.