It’s a funny paradox to look back on classic science-fiction films. In one instance they prognosticate a future that, in most cases, has already happened. Additionally, whilst venturing into futurity, they can’t help but be time-capsules of the era they were made in.

But good science fiction, no matter when it it was made, remains timeless as it abides by the genre’s willingness to explore the human condition in imaginative creative speculative ways. To find hidden treasures buried beneath the many blockbusters we know and love is a treat for any fan of the genre. That being said, it’s quite hard to determine what is and isn’t lesser-known, particularly when writing for such film-buffs as yourself. I can only define it as a film that does not usually circulate within the circuits of conversations amongst us cinephiles…

With that out the way, here are ten lesser-known science-fiction flicks that occurred a long time ago – but thankfully in our own galaxy, ready and waiting for you to watch or revisit.

10. Z.P.G (1972)

In a smog-filled 21st century, the law of Zero Population Growth (Z.P.G) prohibits natural born children; but would-be parents Russ and Carol McNeil (Oliver Reed and Geraldine Chaplin) dare to defy this dystopic regime by secretly bearing a child. Though its mese-en-scene – from milatiran uniforms to oppressive city-scape surroundings – might seem like an overt echo of what we know and come to suspect from dystopias, the apposite problem of over-population manages to reverberate far greater today in our own expanding modern world.

Director Michael Campus explores this ever-prescient issue through the broody solid performances of Reed and Chaplin, who as the McNeils feel like downtrodden people caught in this strange autocratic dystopia. In shadowy bedtime reflections they ponder and debate the perverse present they find themselves in; two humans clinging on to their humanity, and daring, despite the danger, to fulfil their paternal instinct. As underdogs against the system the McNeils are endearing, if a bit dour. There is a charming interplay in this film between the sentient and the synthetic, reinforced by the inclusion of “life dolls”, creepy chucky-esque toys dished out to those with the itch to bear children, certifying this new future into the realm of the uncanny.

Though the Z.P.G edict may have been put in place to protect humanity and its strain on the earth, it has made life on the planet very strained indeed. Though the film’s pace may be slow, its thematic discord about unravelling societal roles and the importance we place in them as a species remains interesting and thought-provoking.

9. Seconds (1966)

Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) takes on a clandestine company’s offer to give him a “Rebirth”, including new face, life and identity. The portly Hamilton becomes beefcake painter Tony (Rock Hudson) – a definite improvement, so it would seem; but as director John Frankenheimer exhibits so well in this sci-fi thriller, surface does not equate to our substance.

Hudson is excellent as the transmuted Tony, perhaps delivering his finest performance. Playing the outward appearance of his dashing self as well as the existential old man inside him is no mean feat, with lovely hunches and shuffles sneaking into his physicality – his sad gaze betraying him for a man far older than his seemingly youthful years. Hudson embodies the concept of the Rebirth – the reconfiguration of one’s umwelt – how we see the world and are seen by it – proposing a very nuanced cerebral and psychological science-fictive concept.

But why such trouble in paradise? Frankeheiemr makes the brilliant decision to give his protagonist the ultimate wish, offering an unhappy individual a utopic life, away from the modern corporate world and the anomie of the city in favour of a swanky Malibu beach house, complete with a tireless butler who brings him party invitations. But a utopia that isn’t striven for is empty and superficial – by not living life as it is meant to be lived in all its complications, an unnatural existence is inadvertently created, helped by a horrific organ score by Jerry Goldsmith.

Distorted close-ups and over-shoulder shots exemplify this claustrophobic nature of living in a second skin that is not our own, and the Kafkaesque nature of spiritually searching for oneself by trying to be somebody else; how the body, no matter which one or how many rebirths, is merely an avatar. It is the spirit inside us, not the crude flesh that dictates whether we want to grow into decent human beings or not. Seconds is a film that inversely explores this obligation to be better, embodying the ethos of sci-fi.

8. THX 1138 (1971)

THX is known to many film-buffs, but it is certainly lesser-known when looking at the filmography of Mr George Lucas and his moderately popular space saga that dominates it.

Staged on a far smaller scale and with an even greater indie-daring and flare for the experimental, THX (Robert Duvall) and SEN (Donald Pleasance) attempt to escape from a futuristic totalitarian society. Their plight to flee a world ravaged by corporate consumerism and iatrogenic pill-pushing is brought to life by Lucas, who demonstrates his pedigree as one of the finest filmmakers of our time.

The film is a saturnalia of synesthetic delights, with its futuristic soundscapes and trippy audio purposely out of sync, creating a warped discombobulating world. But Lucas is a great visual storyteller as well as a great filmmaker; he could have easily told THX without any sound, with images and colours beautifully illustrating this futurity; from the cold clinical whites of the uniforms (much like the stormtroopers of the Star Wars saga) and white prison room that outlines a pristine autocratic regime, to the black nightmarish suits of the robomen and their antithetical silver masks, the faces of an technocratic world with no cares for the cries and pleas of the human individual – all of which makes a scary vision brought to you by a budding visual virtuoso.

Robert Duvall gives a touching and understated performance as a man gripping on to the last vestiges of his humanity in a world that tries to stamp it out. Lucas, the anthropological graduate, has stretched what was once the basis of a short film into an engaging study of the human animal and how far it will go to retain its humanity before it can be turned into a baseless machine.

7. Outland (1981)

On Io, Jupiter’s sunless third moon, honest marshal O’Neil (Sean Connery) takes on his crooked mining colony as they succumb to a deadly enhancement drug, setting the space-stationed stage for what is an awesome 80s drug-bust told through a scientific lens. Director Peter Hymas crafts a gritty world that feels very Alien-esque. The colony feels weathered, louche and lived-in, complete with the grease and steam of a cafeteria that proves to be an excellent arena for a fight sequence – one of many peppered amidst this thrilling mystery.

Connery is excellent as O’Neil, delivering an everyman quality, but embodying the best of your typical everyman – though struggling with the pressures of his job, he prevails with resilience, commitment and a drive to watch out for his men and do the right thing for his family. He’s an old-school hero with a no-nonsense moralism, matching him up beautifully against a modern disreputable workforce. There is also a nice working-class can-do attitude to his approach and an endearing willingness to get his hands dirty and stick to his values.

O’Neil’s fight against drugs is is a worthy clash, with the incorruptible marshal fighting against a substance that terribly corrupts others. Not only does it chime with the crack epidemic of the 1980s, but it rises above the clichés of the topic. Far from Just Saying No, the film dares to propose that the drug-taking is a symptom of a far greater wheel of corruption, stemming from corporate greed and a rebarbative capitalist agenda. O’Neil realises this; his decision at the end of the film feels right and earned, and is a worthy telling of the individual triumphing over the system – a rediscovery of the self and a sanctifying of the soul.

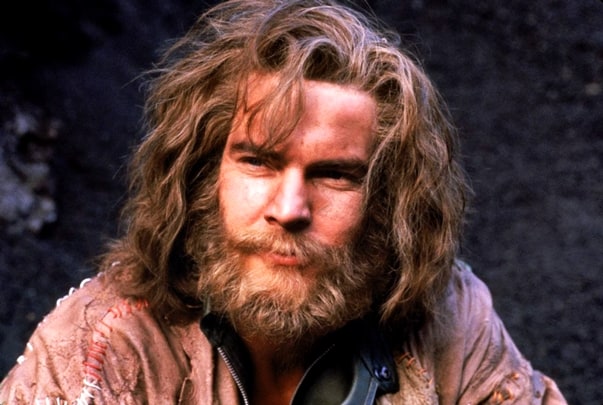

6. Enemy Mine (1985)

During a war between the human race and a reptilian species known as the Dracs, hotshot space pilot Willis Davidge (Dennis Quaid) and enemy solider Jeriba Shigan (Louis Gossett Jr.) are forced to put their differences aside and work together if they are to survive a hostile alien planet that both fighters have crashed landed on. The premise is simple but effective; its 8os panache for action and adventure provides stellar entertainment and pure escapism, becoming a swashbuckling microcosm of what feels like a much larger space opera, helped by gorgeous set designs by Rolf Zehebauer, from planetary peculiarities to ship designs.

But what really makes this story sing is the character work, and the evolving relationship between our two main characters, both entrenched in their seemingly opposite beliefs, but, through action and circumstance, realise that they are not so different after all. Quaid and Gossett Jr give consummate performances, particularly the latter for making us feel through layers of rubbery makeup that should have gone on to won an academy award. With shades of The Defiant Ones (1958), director Wolfgang Petersen has made a timeless and universal story of friendship and identity, celebrating unity and friendship over difference and division.