6. High-Rise (Ben Wheatley, 2015)

Previously regarded as being unfilmable, J.G. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise was eventually adapted by the recurringly ambitious Ben Wheatley in 2015. The similarly unorthodox Nicolas Roeg had reportedly been interested in adapting the story while Ballard fanatic David Cronenberg only indirectly riffed on the story in his 1975 film Shivers. It was only ever going to take a brave soul to finally achieve it; the type of director that would be bold enough to re-adapt Rebecca or cast Armie Hammer in multiple projects.

High-Rise follows the lives of residents of a revelatory new style self-contained apartment complex, equipped with a supermarket, swimming pool and gymnasium. However, chaos ensues as the inequality between the working classes at the bottom of the tower and those ruling at the top becomes more strained and the technical faults of the building become exposed. Tom Hiddleston stars as the sociopathically composed Doctor Laing who drifts through the mayhem, avoiding getting his hands too dirty.

All of Wheatley’s works contain a sly, dark humour and this is as present as ever in High-Rise as he revels in the carnage, playfully depicting the messy downfalls of this flawed society. The rich, who previously used to attend parties on the highest floors in pompous 18th century Georgian attire, are reduced to eating dog food out of cans and living in filth. The supermarket is swarmed by inhabitants who wrestle over cornflakes and are prepared to fight to the death over the last tin of paint. The tower block descends into complete hedonistic anarchy as people have sex wherever they feel and with whoever they want.

All of the cast understand the heightened, explicit world that they are being asked to create and they excel in it. Jeremy Irons thrives as the ministerial, overlord architect of the building as he becomes increasingly less distinguished while Luke Evans depicts the upstart revolutionary, Richard Wilder, who becomes as increasingly brutish and aimless as his name suggests.

Set in an alternative depiction of the 70’s, the homes of the complex are coated in orange and yellow floral wallpaper patterns and the men bestowed with thick moustaches. ABBA’s “SOS” is sumptuously reimagined by Portishead in a slower, stringed style that matches the atmosphere of the surrogate, retro-futurist past that Wheatley envisioned. High-Rise ends with a little boy, Toby, listening to a speech by Margaret Thatcher on a portable radio, ironically foreshadowing the arrival of the 80’s. If the working-class citizens of the high-rise thought that the 70’s were tough and unjust, then just wait until they experience Thatcher’s Britain.

7. THX 1138 (George Lucas, 1971)

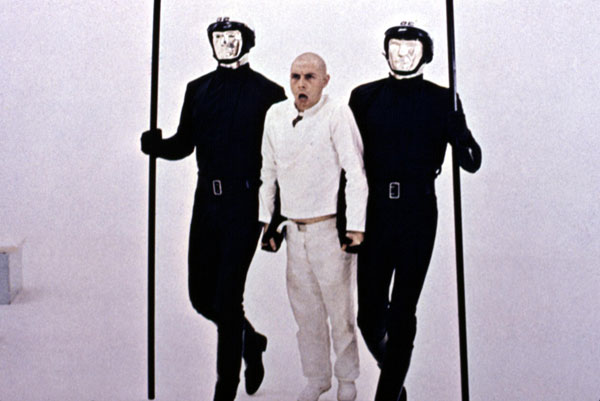

George Lucas’ debut feature THX 1138 is set in a clinical, totalitarian future where people live mundane, controlled lives under the influence of government-enforced drugs. Completely dehumanised and bereft of emotions, the population are assigned not names but three lettered prefixes followed by four numbers and are expected to carry out their functions and nothing else. When the eponymous THX 1138, played by Robert Duvall, becomes deprived of his medication, he is targeted by the state and arrested for his lack of compliance.

The human race is a colony of homogenised slaves in THX 1138 as men and women alike are completely bald and dressed in white uniforms. Often only backdropped by vast expanses of white nothingness, the inhabitants appear as porcine silhouettes; anonymous figures in an anonymous world. Workers at computers overheard that speak only in jargon and code refer to the citizens as little more than objects, ordering what must be done with them and when.

As THX 1138 is experimented upon, workers watch through a screen, absently suggesting different ideas to test on him as if he were a beta computer programme. Android police enforce conformity as they shepherd the people, often represented as more autonomous and sentient than the humans themselves as they speak politely towards one another and are designed in more recognisable clothes – their steel faces the only giveaway of their robotic nature. When tracking down THX 1138, one android officer calls for assistance by saying “it would be nice to have some additional officers” in a way that is completely darling.

There are hints towards Lucas’ future success in science-fiction in THX 1138, particularly through the sound mixing. The choreographed clashing of sounds in the finale’s high-speed chase and the overlapping yet clear radio communication between workers indicates the later similar use that would be used to tremendous effect in Star Wars. It should be unsurprising that the creator of arguably the most influential, successful film of all time would have had such an accomplished debut feature but Lucas’ immediately mature direction and depiction of the dystopian world still impresses.

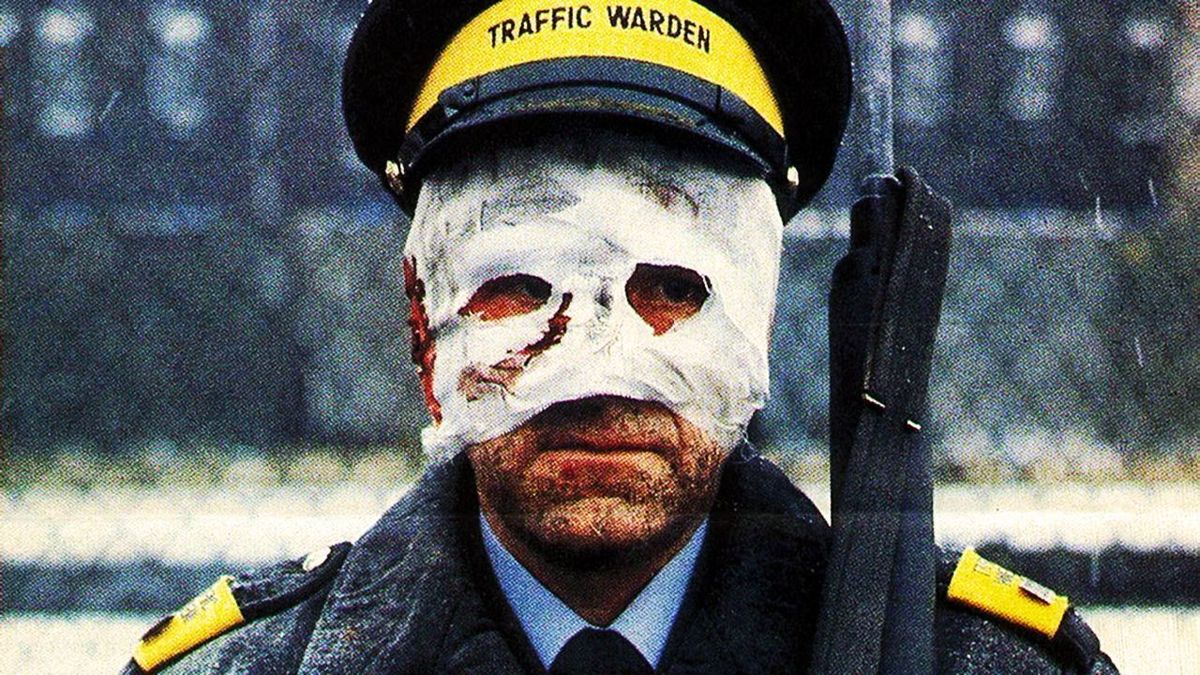

8. Threads (Mick Jackson, 1984)

One of the most distressing, depressing films ever made, Threads presents the life of civilians in Sheffield before and after a nuclear attack. Based on real protocol and predictions of the effect of a blast, Threads depicts a hyper-realistic, nightmarish vision of society that would have felt terrifyingly close to home at the time as relations between the USSR and the West became increasingly tense. What’s more, as it was produced by the BBC directly for television, you can only imagine the number of children that were permanently scarred by accidentally watching it.

The opening thirty minutes of Threads play like a primetime soap-opera as we follow the daily lives of different families with their menial drama, making it all the more shocking after the city is thrown into desolation and depravity. We are immediately introduced to Ruth and Jimmy, a young couple who are expecting their first child and plan to get married.

There are occasional news broadcasts that play out in the background describing rising tensions between the USA and UK with the USSR over events in Iran and the possibility of violent action being taken, but these go largely unnoticed by the protagonists as they are much more concerned with meeting each other’s family and decorating their new home. It all rather seems like media sensationalism and scaremongering that shouldn’t be taken too seriously meaning that when the inevitable strike does occur it still feels quite unexpected. Jackson holds back nothing in depicting the devastation of the nuclear blast as children and family pets are burnt to a cinder.

Unrecognisable ashen remains are buried in the rubble that used to be their homes like the bodies of Pompeii. They could be Jimmy’s friend from the pub or the ladies that they chat up but there is no way of knowing now. However, those are the lucky ones. Survivors live desperately in basements and homemade shelters; disfigured and poisoned, they are sick onto themselves and soil their beds. Society crumbles as plumbing and electrics fail and there is not enough food to share. Officials attempt to restore order which ultimately slides into an authoritarian control as they find that rifles are the most effective way to manage the wretched populace.

Months and years pass as the time is dictated to us by clinical intertitles that describe the predicted progress of the people. Tess and her child survive within a farming community that attempt to cultivate the polluted soil. Life is hard and relentless, but there is life.

9. World on a Wire (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1973)

Directing 44 films in only 18 years, Rainer Werner Fassbinder was forever challenging himself to take on different projects that examine the flaws and prejudices within society. Although this was usually in the form of contemporary or historical melodramas that explored race, class and sexual orientation, it is no surprise that Fassbinder eventually took to the dystopian and imagined a world with its own unique imperfections with World on a Wire.

Originally made for German television as a two-part mini-series, the film chronicles Fred Stiller, played by frequent Fassbinder collaborator Klaus Lowitsch, as an engineer at a cybernetics company who begins to investigate the workings of a new virtual reality supercomputer that has created a world in which 9,000 occupants live, unaware that they are inside of a simulation. Foreshadowing similar ideas that would be aroused in The Matrix series almost two decades later, World on a Wire is a philosophical examination of existentialism and technology that has only become more prescient with age.

World on a Wire begins in the guise of a murder-mystery as Stiller investigates the puzzling death of Professor Volmer, the previous technical director of the artificial world program who seemed on the edge revealing an astounding discovery. As other workers go mysteriously missing, Stiller is perplexed to find that not only have they disappeared but other members of the company don’t even remember them. Convinced of a conspiracy, our protagonist delves deeper into the uncertainty, even travelling into the simulator himself to find answers.

Evoking questions around determinism and free will, the ideas in World on a Wire have become increasingly relevant over time as advances in technology suggest that it is entirely possible that our own world could all just be a simulation. Although the notion that life on Earth is an illusion is not exactly ground-breaking (essentially being argued since the dawn of religion from the Bible to the Bhagavad Gita) it now feels scientifically more possible as we ourselves can digitally conceive of it.

10. Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

Set at the precipice of the new millennium, Strange Days imagines what life will be like four years after it was made. Bigelow combines a variety of issues and anxieties of the time ranging from the dangers of technology and Y2K to police brutality and racism. Set in Los Angeles, the world presented is not drastically dissimilar to that of the rest of the nineties except the development of SQUID, a black-market technology that allows the direct recording of memories and physical sensations so that they can be experienced by others like ultra-visceral virtual reality. Users can experience sexual pleasures and adrenaline rushes that they would never be able to do in reality while also being able to relive their own memories as if it were the first time. Lenny, played by a deliciously greasy Ralph Fiennes, is a SQUID dealer that becomes dragged into the hunt for a killer after he is sent the recording of a friend being viciously murdered.

Kurt Cobain may have died the previous year but Strange Days only imagines that the nineties will get even Grungier as it goes on. People set fire to cars in the street as others attend a caged nightclub called Retinal Fetish where the poster girl of grunge cinema, Juliette Lewis, performs PJ Harvey songs on stage. Meanwhile, the poster boy of nineties sleaze, Tom Sizemore, shares his very nineties philosophy that it must be the end of the world because everything has been done and nothing is original anymore. It’s funny how cute and naïve this brand of cynicism seems now in the post-9/11, Trumpian era.

Unfortunately, what is still sadly relevant today is Strange Days themes of institutional racism and police corruption. Following the injustice of the Rodney King trial and the subsequent riots, Kathryn Bigelow felt impelled to include the racial tension and police brutality inherent in American society as part of her story in the form of two LAPD cops, played by Vincent D’Onofrio and William Fichtner, who cold-bloodedly murder a fictional African-American rapper. Although somewhat clumsily shoehorned in, it is still an important reminder of how little the treatment of non-Caucasian citizens has progressed in America over the last thirty years.

Ralph Fiennes and Angela Bassett both produce great performances: Fiennes playing wildly against type as the deadbeat but loveable memory-dealer while Bassett plays completely to type as the strong and confident Mace. Strange Days may not be as drastically different to reality as a lot of the other films on this list, representing a future that at the time was only a few years down the line, but it stylishly and excitingly depicts a Los Angeles filled with angst and on the brink of anarchy. Although Bigelow presents a generally pessimistic view of life in 1999, one thing she was surprisingly optimistic about was the relevancy of laser discs as, even in the four years between the film’s release and setting, the medium had already become widely obsolete.