The debate over film authorship has always revolved around the director. He or she is the one often bearing most of the credit for a production involving hundreds of people and roles. When Film is discussed in an academic or critical manner, it is always the director who is placed in the role of author for any particular film.

It is natural for this to be the case. The director is responsible for how the actors act, how the story unfolds, and everything else going on in front and behind the camera. But the role of the cinematographer, or director of photography, can be just as crucial to the success of a film. The cinematographer is in charge of working with the director to establish how the film they are working on will look. They are then tasked with turning this plan into reality. They oversee lighting, framing, color, and everything related to visuals. It is a job that requires high artistic and leadership skills.

There have been many great cinematographers who have become critically renowned and financially successful through their work. There have also been some greats who, for some reason or another, did not reach mainstream recognition. Among these is Robby Müller. This Dutch cinematographer was responsible for some of the most visually captivating cinematic imagery of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. While he was never nominated for a major award, his influence and reputation are notable among film-circles.

Known for his mastery of natural light, he found frequent collaborators in directors like Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, and Lars von Trier. Keep in mind that the fact that he worked so frequently with these directors will be reflected on this list. Yet his filmography is extensive and varied. Having worked mostly in independent film, he was able to have more of a say in the creative execution of many of the films he worked on. Müller passed away in 2018, leaving 33 years of amazing cinema to the world. Here are ten of his most beautiful films.

10. Kings of the Road (1976)

Perhaps the most frequent collaborator of Müller was German director Wim Wenders. It looks like the pair found in each other a perfect filmmaking counterpart. Film curator Jaap Gulemond said Müller “was really looking for soul mates, as he calls them . . . All the different directors he worked with were people with whom he felt at ease, people he liked, and with [whom] he could do what he wanted to do” and Wenders was probably his main guy. The duo collaborated in eleven films from 1970 to 1995, making Wenders Müller’s most frequent collaborator. In fact, Wender’s directorial debut Summer in the City was Müller’s debut behind the camera as well.

In the mid-70s, they collaborated in a road movie trilogy, the last part of it being Kings of the Road (Im Lauf der Zeit). The story revolves around the relationship between Bruno and Robert, a film projector repairman and a depressed man respectively. Bruno finds Robert after the latter drives his car into a river in a half-assed suicide attempt. Bruno takes Robert with him as they traverse flat German countryside, stopping at small-town movie theaters to fix projectors.

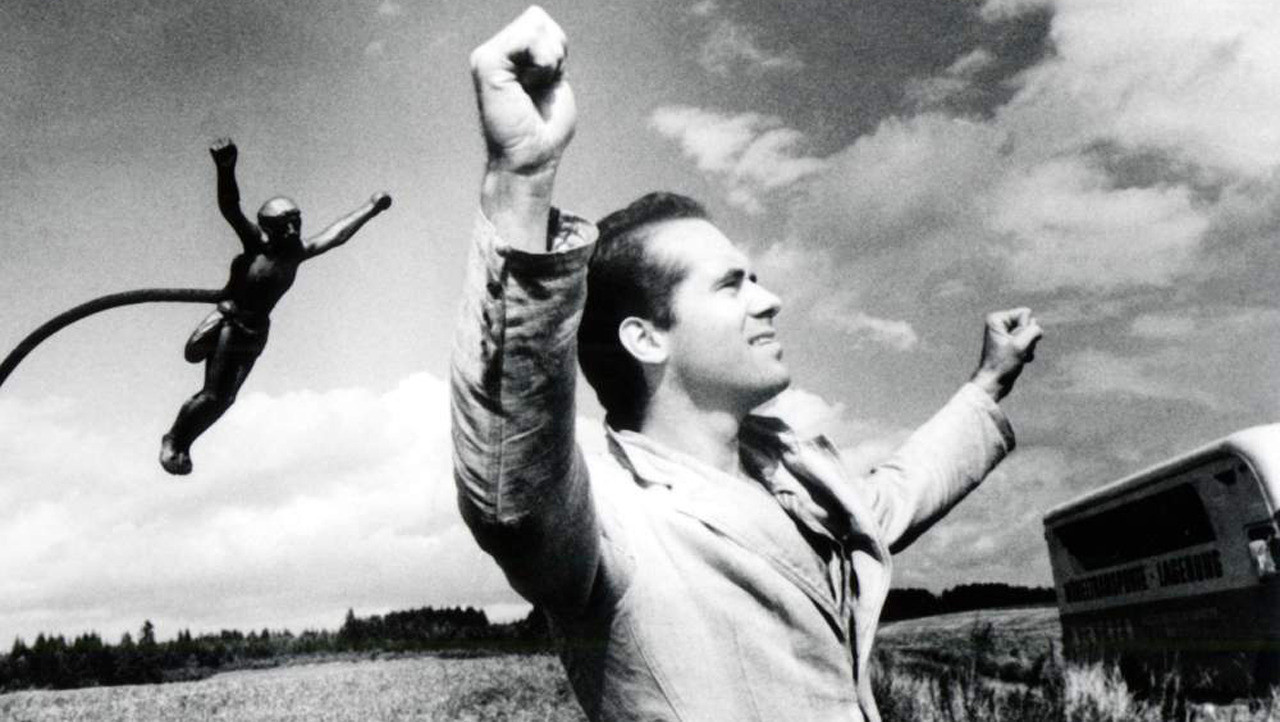

The film was shot in black-and-white. Wenders decided this as he thought it was “much more realistic and natural than color.” Its visual style is stylized yet appears strongly naturalistic. Wenders and Müller achieved this through various techniques. One of these was the long-take. Kings of the Road included many long-takes, often without any dialogue, that allow the characters to casually inhabit the landscape. The end result is a beautiful film of desolate roads and dingy towns with a friendship storyline that unfolds naturally. It might not be the best film the duo ever made, but it is an excellently crafted and atypical road movie.

9. Down by Law (1986)

Another of Müller’s “soul mates” was American indie filmmaker Jim Jarmusch. According to Jarmusch, in 1980 he was in Rotterdam showing his first film Permanent Vacation. He loved Müller’s work and asked Wenders how he might be able to meet him. Wenders told him to go to the bar and he’d find him next to the peanut machine, which he did. “So I sat down next to him and started talking to him. And we hung out quite a bit at the festival and he saw my first film, and he said to me eventually, ‘If you ever want to work together man, let me know”.

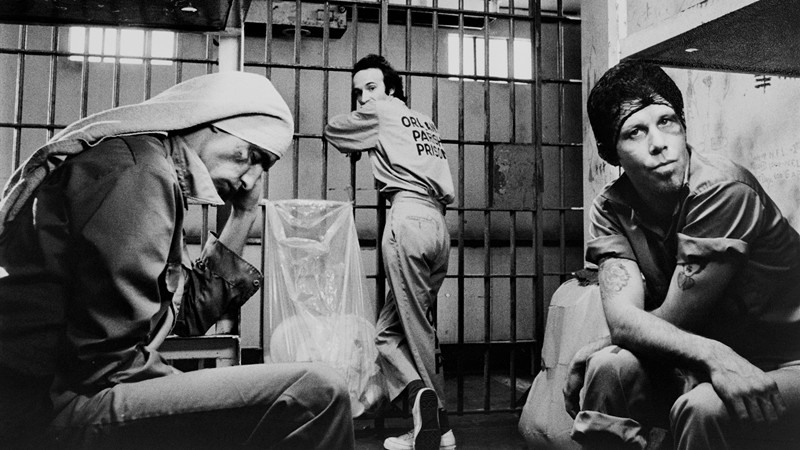

So when Jarmusch wrote Down By Law, he called Müller. And so began a partnership that would result in five pictures. The film tells the story of three inmates in a dingy Louisiana jail and their attempt to break out. It’s a bluesy, humorous, and soulful movie with great performances by Tom Waits, John Lurie, and Roberto Benigni. Jarmusch wanted to shoot the film in a naturalistic, black and white style, and what a better man for the job than Robby.

Down By Law looks incredible. Müller made use of very basic photographic techniques to create scenes that seem both real and dreamlike at once. It is evident that Jarmusch and Müller were in complete accord with each other on the essence of the story. He was therefore able to shoot it in a way that perfectly complemented it. It’s certainly some of the best work Müller ever did, and proof of how he could make so much with so little. “I think he’s like a Dutch interior painter, like Vermeer or de Hoeck, who was born in the wrong century” Jarmusch once said of his longtime collaborator.

8. To Live and Die in L.A (1985)

The year before making Down By Law, Müller collaborated with Hollywood giant William Friedkin in what would become one of his well-known films. Friedkin wanted to make the film fast and hired Müller because of his reputation for efficiency. The film is a neo-noir set in Los Angeles. Based on the novel of the same name by Gerald Petievich, it tells the story of a Secret Service agent Richard Chance (played by William Petersen) assigned with investigating a counterfeiting racket run by Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe).

It is a gritty thriller that is as visually arresting as it is dramatically engaging. Although Müller never worked with Friedkin again, they complemented each other well, and he was able to match the director’s vision. Friedkin urged his actors to improvise, something which is hard for a cinematographer to shoot since they don’t exactly know how and when the actors are going to move. During a particular scene, he let the actors decide their own blocking and told Müller to “just shoot them. Try and keep them in the frame. If they’re not in the frame, they’re not in the movie. That’s their problem”.

Friedkin’s film is probably the movie with the most action sequences that Müller ever shot. Some of which became iconic of the genre and period, such as a thrilling chase through Los Angeles International Airport. If anything, To Live and Die in L. A is proof of Müller’s ability to work across genres and work in higher budgets productions and with more costly equipment.

7. Barfly (1987)

After several successful productions in America, Müller was hired by Iranian-Swiss director Barbet Schroeder to shoot Barfly. The film is a semi-autobiographical tale of an alcoholic in Los Angeles, with the screenplay written by legendary American writer Charles Bukowski.

The story follows the protagonist, Henry Chinaski (Bukowski’s alter ego, played by Mickey Rourke), as he spends his days working odd-jobs and getting drunk at dingy local bars. There, Chinaski drinks, mingles with other alcoholics, and gets into fights. Henry meets Wanda (Faye Dunaway), who is taken by his wit and humble intelligence and the two begin a turbid relationship.

In Barfly, Müller employs various techniques to give the film a grimy, metropolitan look. The lighting in the bar scenes is dominated by a combination of neon and shadow. The day scenes are shot in an organic yet playful way, with great use of long-takes. While the film wasn’t very successful it was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes and earned Faye Dunaway a Golden Globe nomination. Müller was nominated for Best Cinematography at the Independent Spirit Awards as well. It was well-received by many critics, including Roger Ebert, who gave the film a 4/4 rating and called it “a truly original American movie, a film like no other”. While it is not the most well-known or influential work Müller ever did, it’s a funny and well-acted 80s flick, well worth a watch.

6. Mystery Train (1989)

In 1988, Müller and Jarmusch teamed up again to make Mystery Train. After Down By Law, Jarmusch and Müller became good friends, and they agreed to work together again in the future. Jarmusch had written the script for Mystery Train and was planning on shooting on location in Memphis. When Müller was offered the job, he immediately took it.

Mystery Train is about Memphis. Jarmusch explores the tall tales, culture, and people that are part of the city, from different perspectives. The film revolves around three stories that take place during the same night. In the first one, two Japanese tourists obsessed with the blues travel around the city. In the second, an Italian widow encounters the ghost of Elvis Presley. In the third, a trio of locals rob a liquor store and hide out in a hotel. It is in this hotel that the three stories intersect and intertwine, and Jarmusch playfully incorporates events from one story into the others.

It is a funny and mostalgic film with a great construction of atmosphere. It was Jarmusch’s first film in color and he worked with Müller to create what he described as an “intuitive” color scheme. Müller’s camera work is again one of the film’s most redeeming qualities. It’s packed with languid long takes, clever color-coding, and a grimy characterization of the city of Memphis itself. Mystery Train is the cinematic equivalent of an old bluesman telling a story at a bar, and one of Müller’s and Jarmusch’s best.