5. U Turn (1997)

Oliver Stone entered the ‘90s as one of the most powerful and celebrated auteurs in Hollywood, but after years of increasingly more byzantine formal experimentation, public polemic, and dwindling box office returns, his reputation by the end of the decade had taken a serious hit, turning him into a troublemaker who wasn’t worth the trouble.

“U Turn” was clearly a job the filmmaker had to take due to the commercial failure of his previous features, and it’s a definitive outlier in a decade marked by much more personal passion projects like “Nixon,” “JFK” and “Natural Born Killers.” But no matter the circumstances, it was a good move: the go-back-to-basics nature of it reels in Stone’s more excessive instincts, but doesn’t preclude his and Robert Richardson’s formal trickery, which in this case is a perfect fit for the story, a nihilistic but incredibly funny slice of neo-noir.

Morricone’s work is equally off-kilter, with strange, dissonant sounds that marry perfectly to Stone and Richardson’s ragged images.

4. The Sicilian Clan (1969)

A cross between Melville’s exacting crime dramas and the more laid-back Hawksian hangout movies masquerading as genre pieces, “The Sicilian Clan” is the kind of breezy, well-crafted caper we so rarely get anymore, but which provides unequal pleasure for genre fans.

The main attraction here is certainly the murderous row of French acting royalty, featuring three generations of legends: watching Jean Gabin, Lino Ventura and Alain Delon sharing the screen is such a joy for cinephiles that the movie is worthwhile for that alone.

But for those less familiar with French cinematic history and don’t have an attachment to these actors, don’t worry – “The Sicilian Clan” is filled with incredible individual sequences of sustained suspense, two of which are among the finest of all time: the initial jail break and the climatic hijacking of a plane, sequences shot and edited with such skill and specific intent that it’s puzzling why director Henri Verneuil never made anything of note again.

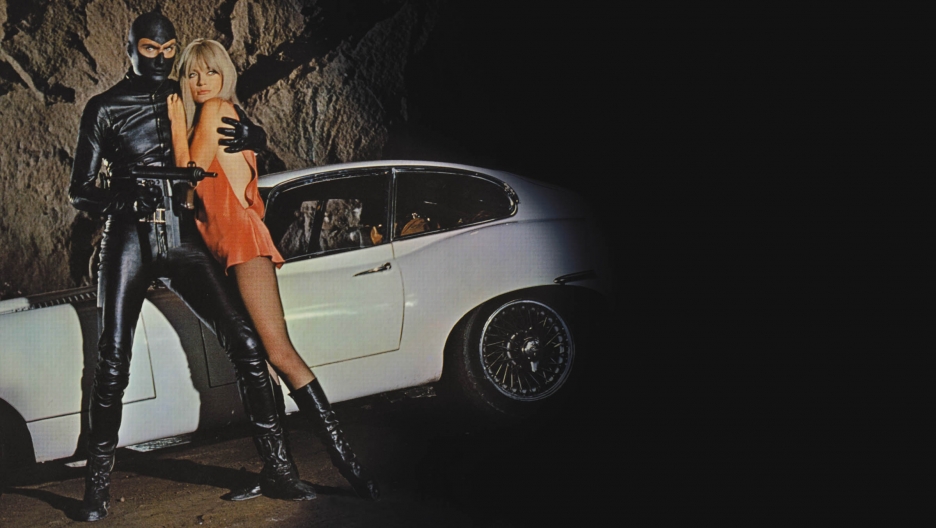

3. Danger: Diabolik (1968)

Mario Bava is one of cinema’s greatest visual stylists and, though he is primarily remembered for his numerous horror classics, the movie that perhaps best represents his aesthetic of psychedelia and complete artifice is “Danger: Diabolik.”

For those not aware, this film is based on a famous Italian comic series and it’s a strong contender for the greatest comic book movie of all time, a sort of artifact of just how subpar most other movies of its kind are by comparison, demonstrating the difference a filmmaker with vision can make. It’s testament to Bava’s untamable creativity that, despite decades of comic book movies saturating the form, this film still feels so utterly distinct. The bravado of the director’s stylistic choices remain every bit as astonishing today; perhaps even more, when one considers this movie’s bountiful colors, lavish production design, and maverick special effects in the context of the grey blandness that has come to define the vast majority of modern comic book cinema.

And, my God, the brilliance of Morricone’s score cannot be overstated: romantic, psychedelic, vibrant, and simply incomparable. Anyone who has had the pleasure to listen to it will never hear the others “Deep down” again remembering “Danger: Diabolik.”

2. Face to Face (1967)

Aside from Leone and Corbucci, there was yet another Sergio of great importance to the spaghetti western: Sollima. Granted, by comparison he made fewer movies in the genre than his namesakes, branching out into other kinds of films (particularly poliziotteschi), which perhaps explains why he’s less discussed as a seminal member of the movement. However, he made two westerns that should’ve been enough to grant him just as much clout as the other Sergios.

The first, “The Big Gundown” is a bonafide classic adored by all spaghetti fans, but he made another one immediately after that is arguably even better but somehow forgotten even by western connoisseurs: “Face to Face.” That’s perhaps because the film is far less pulpy and action heavy than most other spaghettis; Sollima made something much more political and psychologically complex, trading out the broad archetypes that usually populate the genre for strong, specific, complex characterization.

It’s more intimate and inward looking than what one would expect from a classic shoot-em-up (even Morricone’s music is fairly subdued by his standards, especially considering his other western scores), but don’t worry, the film still delivers every bit of the ultraviolent confrontations between cowboys, shot by Solima in the ever-beautiful Panavison compositions. One of the very spaghetti westerns ever made.

1. The Battle of Algiers (1966)

The understanding of what constitutes “political cinema” has been so diluted down so as to lose any of its original meaning, the term is now thrown around so frequently and indiscriminately that anything featuring a character saying a progressive buzzword counts to a certain section of the thinkpiece industrial complex as “political.”

Gillo Pontecorvo’s seminal masterpiece “The Battle of Algiers” is what real political cinema looks like: thoughtful, visceral, complex, thematically wide-raging and lacking in any easy answers to difficult problems. Rarely in the history of cinema has form and content been married to such an exquisite extent, Pontecorvo’s quasi-documental approach (a then-revolutionary aesthetic before it came to be the crutch of every hack with no discerning sense of visualization) and use of mostly non-professional actors (a lot of whom had actually participated in the conflict) add a layer of realism and integrity to the film, one that makes the director’s inquiry into the many layers and nuances of the Algerian struggle for independence feel actually honest and empathetic, rather than a privileged artist’s detached exploration of the misery of the disposed (something that so often happens in other movies made by rich people who allegedly care about the oppressed).

“The Battle of Algiers” is simply one of the greatest movies of all time, one that any cinephile should make an immediate priority of.