It has become almost a cliche to compare modern films to ancient myths, and yet it’s all too fitting a comparison, both a way in which to transfer stories across different generations. These stories get retold, re-screened, as they record a certain cultural experience that reflects the times we live in.

Film is especially uncanny to the practice of myth-making given how adaption is a staple within the industry. There are four versions of A Star is Born, twenty-six James Bond films and countless reincarnations of Dracula. We expect to see new faces revive old characters. What this tells us about movies in general is that on some level, we acknowledge their role as archetypes, as stories that are constantly being reshaped as the years go by in order to resonate with a new audience.

Rather than have people huddled around a night-time fire, telling stories of warriors and gods by a single source of burning light, today we gather in the darkness of the cinema, and again, a single source of light projects for us the stories of love and death, hope and loss. After all, the word myth originally meant simply ‘story’ or ‘narrative’ rather than having any grander connotations; but this grandness that we now associate with myth is a part of cinema too; the largeness of the screen, the sublime scale of emotions. We identify our most celebrated actors with ‘stars’, a fame that’s so large that it becomes almost cosmic.

Though there have been tons of films that straight-up adapt myths – Clash of the Titans, Jason and the Argonauts – many films simply borrow from these Classical tales, borrowing structure or character types. Some films are more flamboyant with their allusions, though they maintain their own story set in modern times. Some films can’t help but blend their own fiction with the ancient fictions that began this whole process of story-telling in the first place.

1. The Lighthouse (2019)

In addition to its dreamy black and white imagery, a haunting soundscape, and an ending that will give Eraserhead a run for its money for freaky electrical climaxes, Robert Eggers’s The Lighthouse was received with universal acclaim last year. A moody, surreal vision, fished out of German sea etchings and Greek mythology, Eggers’s film tells the tale of two lighthouse keepers who slowly lose sight of reality as they find themselves alone on a remote island.

Thomas Howard (Robert Pattinson) and Thomas Wake (Willam Defoe) both become entangled in an emotional battle for power. Howard feels as though his labour has been abused and that Wake is withholding precious information from him; the looming phallic lighthouse acts as a backdrop to their struggle, one that’s constantly in the periphery of the film, shining a harsh light on the two men as their masculinities ebb and recede in the tortuous time alone together.

Defoe’s character resembles the prophetic sea-god Proteus, whose ability to change shape is mirrored in Wake’s constantly shifting backstory, which evolves into a gas-lighting that helps drive Howard insane – he even envisions Wake as a tentacled, barnacle-ridden sea-creature. Eggers creates a masterful moment of suspense and climax where reality combusts; Howard ascends into the lantern room of the lighthouse, reaching his hand into the light source, a mysterious, other-worldly energy emanating from the lantern. After a moment of reality short-circuiting (a la Eraserhead), the film cuts to Howard’s Promethean fate (the titan who fatally stole fire from the gods); his body emerges through a thick mist, naked, disembowelled, and unbearably, still alive as seagulls pick at his intestines.

The film’s black and white imagery (curtesy of Jarin Blaschke) and 1:19:1 aspect ratio offer us a claustrophobic, old-world environment that renders the distinction between life and dream all the more obscure. But these aesthetic choices also echo back to Eggers’s visual influences, such as the drawings of the fifteenth-century painter Albrecht Dürer, or the German Symbolist artist, Sascha Schnieder, whose work deals heavily with mythology and folklore. The film also resonates with twentieth century psychoanalysis, where figures like Carl Jung used myths and archetypes to navigate the depths of the psyche. In The Lighthouse, mythology is richly used to explore the impending fate of the two characters, who fight not only against each other but against providence, the sea, the spirit-world, and the Unconscious.

2. The Warriors (1979)

Walter Hill’s cult classic The Warriors is well-remembered for its theatrical and dynamic depiction of New York gang culture, where gang leaders, though terrifying, vaguely resemble Scooby-Doo villains – zombie baseball players and violent mimes – this is all set to a backdrop of Andrew Laszlo’s NYC which brings to mind a sort of neon Hades.

In fact, The Warriors is loosely based on the Ancient Greek text, Anabasis, by Xeneophon. The title word itself denotes ‘ascent’ and ‘embarkation’, a mass movement resembling the urban journey that The Warriors must take from Brooklyn to their home turf in Coney Island. After being framed for the murder of a beloved gang leader (Roger Hill), the Warriors need to survive the night if they want to get back home. But like a modern odyssey, their journey is rife with peril and danger, as a bounty is publicly announced for their capture. In the original Greek text, Cyrus is a Persian prince and general, whose murder undercuts the war effort of the Greek mercenaries who serve him; in Hill’s film, Cyrus is reborn as a respected gang leader, whose ambition is to unite the various gangs of the city, to bring an end to turf wars and organise a war against the police and law-enforcers who continuously brutalise these outsiders..

The finale in both the Greek text and the film take place by the sea – in Anabasis, the marching republic reach the shores of the Black Sea at Trabzon, whereas in The Warriors it’s the shores of Coney Island. By inheriting this Classical structure, Hill’s film (as well as Sol Yurick’s 1965 book The Warriors, which the film is adapted from) creates a timeless story of men at war (literally, warriors) and the obstacles they face, external and internal. The Warriors makes explicit through its military Greek heritage that gang war is a matter of land – who owns it, who shares it, who populates it. In short, who runs the city.

3. O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

Despite being on the weaker side of the Coen Brothers’ filmography, O Brother, Where Art Thou? is nonetheless an interesting take on Homer’s The Odyssey. Set during the Great Depression, the film features Ulysses McGill (George Clooney) as an optimistic albeit naive Odysseus, who having escaped jail tries to make his way across the American South to reunite with his ex wife Penny (Holly Hunter), a rather demanding Penelope who has taken on a new suitor. Like The Odyssey, and like most Coen Brother movies, the film is primarily interested in the journey rather than the destination. It’s the detours, distractions and disasters on route that enliven the film as well as its original text.

But being a Coen Brothers movie, it’s hard not to read the various references to The Odyssey (and the unexpected, brash appearance of Homer’s name in the opening credits) as a satire on the nature of adaption. After all, the Coen Brothers don’t shy away from some very blatant references (Ulysses, Pete and Delmar’s infiltration of a KKK rally having an uncanny resemblance to the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Lion’s infiltration of the Witch’s castle in The Wizard of Oz). The film’s title is also borrowed from Preston Sturges’s film Sullivan’s Travels (its own name borrowed from Jonathon Swift’s book Gulliver’s Travels written in 1726). We are sent down a rabbit hole of references in this movie; the more we look into its sources, the deeper the drop.

As highly self-aware filmmakers, the Coen Brothers seem to be making a joke about the nature of historical adaption, rather than a sincere revival of Homer’s tale (neither brother had actually read The Odyssey when they made the film). And yet with flawless performances by actors like John Goodman, as the one-eyed, cycloptic ‘Big-Dan’, and a tantalising though odd-ball scene where our heroes succumb to the allure of three sirens, the film is nevertheless an entertaining watch. The source material, in the hands of the Coen Brothers, reaches some extraordinary and hilarious new heights.

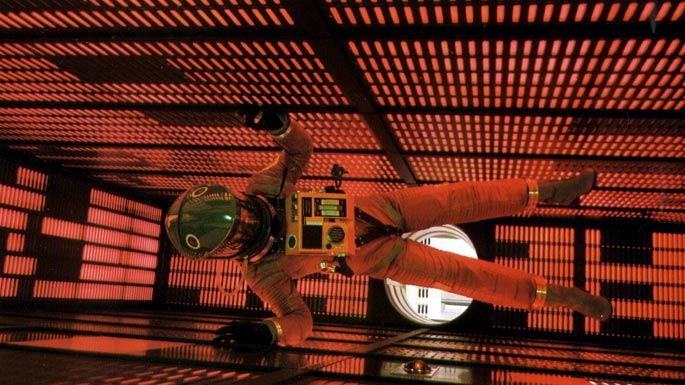

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

A totally different take on The Odyssey was made in 1968, directed by Stanley Kubrick, and it’s perhaps one of the most iconic odysseys of cinema. 2001 is by no means an adaption, but Homer’s tale acted as a literary model from which Kubrick shaped the story.

2001 has had so much criticism, scholarship, and conspiracy surround it that the film evades any simple reading. Many critics have identified in HAL the figure of the cyclops, who Odysseus kills with a stake, not totally dissimilar to Bowman’s (Keir Dullea) murdering of HAL by inserting a small key into HAL’S processor core. The interpretations are endless, Bowman being identified as a modern day Odysseus whose skill in archery has led critics to speculate over the name ‘Bowman’. Though these readings aren’t totally arbitrary; Kubrick himself acknowledged that the way in which the Greeks were fascinated by the sea – viewing it as a vast space which contained the unknowability of the universe – feels very similar the kind of longing that exists in the twentieth century’s obsession with space.

Perhaps this kind of Classical reading of 2001 misses the point slightly, as do all readings that seek to locate a stable source for the work. Kubrick’s film is essentially about the unknown, universal phenomena that escapes human understanding, that escapes human time. 2001 demonstrates how myths have existed since the dawn of time and continue to influence the way we try to read the universe, a universe that operates under a non-linear, multi-dimensional frame. After all, time and space are drastically reshaped as Bowman enters the vortex. Past, present and future all collide into each other, which is perhaps the best way to look at the relationship between time and myth.

5. Funeral Parade of Roses (1969)

Stanley Kubrick has cited Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses as an inspiration for his own film A Clockwork Orange, perhaps in his depiction of an urban underground where violence and pleasure converge, as well as the heavy use of low-light and wide angles. But what’s especially fantastic about Matsumoto’s film is the way it retells the Greek text of Oedipus Rex by setting it in counter-cultural Tokyo.

The film centres on a young drag queen, Eddie, played by the actor and singer Peter, whose androgynous look often led them to play trans roles in Japanese culture. Eddie’s priorities include ascending in status at the Genet club, a nightclub whose name makes a nod to a queer father-figure. Whereas Eddie is a product of contemporary US culture (she would fit all too well into a Warhol picture), she conflicts with the more traditional geisha girls at the club, such as Leda (Osamu Ogasawara) whose relationship with the bar manager creates an Oedipal dynamic out of this found-family, a relationship whose conflicts are personal, political, cultural and erotic.

The film, so preoccupied with the fluidity of identity, takes on a variety of forms to tell its narrative (akin to the French New Wave films emerging at the same time), escaping into documentary, abstraction, and straight up Greek adaption (such as the climactic eye-gouging scene which through the heavy use of subjective shots brings a spectacular intensity to the horror of Eddie’s self-violence). There’s a history of iconic, agonised faces in cinema – the bloody-eyed nurse in Battleship Potemkin, Marion Crane’s scream in Psycho, Joan’s unsettling, soul-penetrating stare in The Passion of Joan of Arc – and the blinded Eddie, blood running from her eyes like tears, belongs in that mythic pantheon of cinema’s agonised women.