Scifi has always been a vehicle for the exploration of philosophical, abstract problems actualized in imaginative technologies, theoretical futures, and alien worlds. Consider the Matrix films’ staging of problems surrounding artificial intelligence, Platonic/Descartian themes of consciousness and reality, in the digestible form of an action thriller, adapted to a reemerging interest in virtual reality technology that remains in today’s age of consumer VR-headsets and a “simulation hypothesis” endorsed by leading figures in the scientific community.

No surprise then that postmodernism found a popular home in science fiction as well. Postmodernism, a school of thought concerned with the deconstruction of popular mythologies and belief systems (the notion of belief-itself among them) took aim at both the political and cultural or formal-artistic forces that created and upheld such mythologies. Popular targets of postmodernism ranged from economic and state powers, belief systems from capitalism and Marxism to Christianity and individualism, and artistically the formal conventions of the singular-perspective narrative which sees an ideological thesis advanced by the insular narrative of a single audience-identity protagonist, and the cultural associations of a given aesthetic more generally.

Standard aspects of postmodern storytelling in film include the use of satire, – critique via acceleration of the real into the absurd – pastiche, parody, and intertextual reference, – emulating the referential-catologic nature of the modern pop-culture soaked mind – the fragmentation, and multiplication of narrative, – the erasure of a single perspective of truth or any complete-unto-itself narrative in the noise of contrasting and conflicting perspectives, significant and insignificant elements, often arriving at the all-inclusive form of maximalism, resulting in a self-conscious and even critical effect of ‘information overload’, increasingly digressive narratives and long runtimes (the average length of a movie on this list being well over two hours) and self-conscious formal disjunction, – a shifting and erratic relationship to tone and aesthetic, fracturing the film itself into films-within-a-film – not only in service of alienating its audience from the illusion of narrative (a Brechtian/Godardian intellectual distance) but also in an imitation of our increasingly fractured attention-deficit media landscape.

And though many of these critiques and techniques have become pervasive themes in the modern media landscape, – and especially the savvy world of science fiction – adopted and co-opted even by those forms and institutions the postmodernists first sought to take down, few films outside the absolute margins of the avant-garde have really taken these themes to their limits the way these next ten films have within the mode of science fiction, sometimes to popular or cult success, about as often to great frustration and confusion. These next ten are not for everyone, but here they are: 10 postmodern scifis to blow your mind & fry your brain. Don’t say we didn’t warn you.

1. Southland Tales (2006)

Following the cult-success of Donnie Darko director Richard Kelly upped the ante with the ultra-ambitious Southland Tales, a sprawling science fiction epic in six chapters (the first three available only in a simultaneously released prequel graphic novel) spanning topics final and wide as nuclear war, totalitarian control, ecological destruction, interdimensional travel, biblical apocalypse, and most overtly and effectively mass media oversaturation and overload (of which the film makes itself a prime example.)

With dozens of characters and interconnected plots intersecting converging and detaching in all directions across its near-future Los Angeles of 2005, the film is a nearly 2½-hour scifi/crime epic loosely centered on a trio of heroes cast self-consciously against type, with wrestling superstar Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as Boxer Santoros, a rock-like media figure and screenwriter played small and skittish and paranoid, Sean William Scott, American Pie bonehead Steven Stifler as Officer Roland Tavener, a cop without a point of humor to him, and Sarah Michelle Gellar, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, as an airheaded celebrity pornstar and parody of the hypersexualized and ultra-commodified reality-TV star, whose individual stories play out across against a backdrop of war between a surveillance state and neo-Marxist terrorist resistance, never-ending war in the middle east, and the accelerating threat of a green energy project called ‘Fluid Karma’, purporting to harness the power of sea-water but really a mass-scale experiment in quantum entanglement which seems to be slowing the very rotation of the Earth.

All of which is only pulp plotting, with the core of Southland Tales being its super-fractured hypertextual presentation which takes the satirical channel-surfing intermissions of Verhoeven’s Robocop and Starship Troopers to its logical extremity constantly filtering the entire film through the media interfaces of its in-world branded reality – a constant screen-fed feed of news, entertainment, and advertisement, (each more or less indistinguishable from the other) as well as the eyes of its ubiquitous surveillance network, in service of world-building, deflected plot transmission, satire, simple disorientation and distraction in equal measure. The frame becomes cluttered with more information than the viewer can possibly take in, and forces them to pick between which of the many information-flows to focus on or else jump erratically between them, adrift in a sea of partial-images.

Panned by critics of the time and a box office bust that would hang as Kelly’s albatross, the film has anyways steadily built a cult following of its own, and begun to finally be reappraised as a serious work of boundary pushing science fiction and filmic experiment within a mainstream form.

2. Cloud Atlas (2012)

In a more mainstream working of similar territory the Wachowski’s Cloud Atlas from the novel of the same name by David Mitchell constructs a thoroughly postmodern history of the human race through the interconnection of seemingly unrelated stories spanning the 19th century through a science fictional 21st century, and a post-apocalyptic 24th, while recasting its leads in various roles across time and space in invocation of both a spiritual reincarnation and the abstraction of individuals into reverberating historical forces – inheritances, connections, and debts.

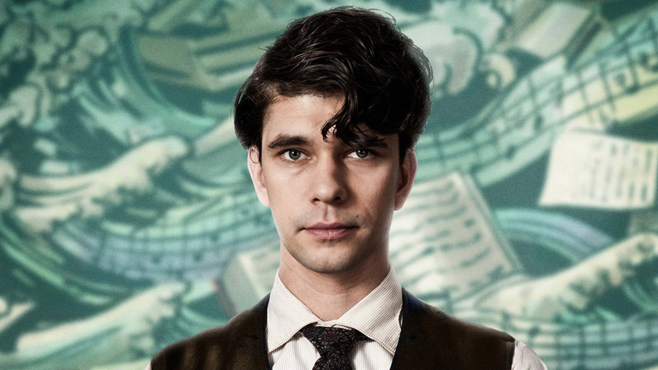

Spanning six main timelines unfolding simultaneously, the film sports a huge cast of Tom Hanks, Halee Berry, Jim Sturgess, Ben Whishaw, Jim Broadbent, Bae Doona, Keith David, and Hugo Weaving playing characters from across time and space – sometimes in questionable prosthetic makeup allowing actors to play characters of different gender and race – in a universal story of the struggle for human dignity against an ever changing backdrop of circumstantial culture, politics, and stakes, playing each story off one another in ways that sometimes parallel and sometimes parody one another.

The emancipation of a black slave Kupaka (Keith David) in the Pacific Islands, 1849, is played against a Korean slave-labor clone (Doona Bae) in Neo-Seoul 2144, and the both of them backdropping the humorous story of an aging publisher’s (Jim Broadbent) organization of a mutiny in a 2012 London retirement home. Meanwhile Luisa Rey (Halle Berry) and Isaach Sachs (Tom Hanks) begin a romance in San Francisco 1973 that seems only to be fulfilled when their likenesses Meronym and Zachary meet in the post-apocalyptic wastes of 2321, and the opus of a young English composer (Ben Whishaw) titled the “Cloud Atlas Symphony” seems to find its way to the hands of many characters through the many seemingly unrelated stories.

Though playing far more into sentiment and mainstream filmic convention than the profoundly postmodern and deconstructive premise of the film suggests, Cloud Atlas is still an admirable undertaking as a treatise on hyperconnectivity and a rejection of the insular narrative.

3. Videodrome (1983)

David Cronenberg’s 1983 science-fiction body-horror Videodrome concerns the strange experiences of Max Renn (James Woods), head of a small time Toronto TV-station after intercepting the rogue signal ‘Videodrome’, a seemingly falsified snuff pornography broadcast Wren is interested in tracking down and acquiring for public distribution.

What Max and fetishist girlfriend Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry) find instead in their pursuit is something much more sinister in the Videodrome signal than even its snuff-perversity lets on, and has something to do with the TV-worshipping media prophet Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), designed with the intent to permanently alter its viewer’s perceptions of reality.

As Wren begins to lose his grip on what’s real, what’s Videodrome hallucination, and the difference between the two, Cronenberg’s signature horror-effects come out with Max developing the VCR deck in his chest made for fleshy pulsating VHS tapes, and a whole slew of TV-colored biomechanical and psychosexual hallucinations besides.

Videodrome is a scifi modern classic for the way its genre and even pulp body horror trappings manage to make one of the most prescient and troubling critiques of mass media since Marshall McLuhan. The media not as a product of simulation or instrument of control, but as an irrevocable intrusion and corruption of the realm of reality. The collapse of the real/unreal duality – where action of the image self – within the mass media subjectivity – means more than any action of the body. And then what dominates this image landscape but the visceral of sex and violence and the manipulations of covert ideology. Reality shaped by our basest instincts and the ulterior motives which prey upon them – militants of the old world perception, censors, fearmongers, unable to navigate the new image reality – and those devoted victims and soldiers of the image’s new flesh, content to leave behind the body behind.

Still relevant, still disturbing, and still a lot of weird fun watching, Videodrome speaks to problems of virtual reality and the psychology of the internet age through its TV-medium better than almost any attempt to address those worlds directly.

4. The Ninth Configuration (1980)

An unprecedented flash of postmodern madness, William Peter Blatty’s (writer of The Exorcist) The Ninth Configuration is the story of Billy Cutshaw (Scott Wilson) an astronaut who is sent to a secret and secluded military mental asylum in a medieval gothic castle of the Pacific North West when his mind breaks on the brink of his first moon mission, struck with the sudden notion that there is nothing really ‘up there’, and the military psychologist, Hudson Kane (Stacy Keach) who is brought in to treat him at whatever expense, by whatever means, as well as an entire crew of loonies besides them, a group with psychoses and delusions so strong to make the Cuckoo’s Nest crew look downright rational.

Every bit as mad as it figures itself to be but only about half as funny, Blatty’s writing surpasses his ability as a director with some clunky comic timing miring what could have been a surrealistic comic masterpiece, but still leaves a profound dialogue between the trained rationalism of the doctor and the inexplicable truths of the patients’ madness. And as Kane gives in more and more to the patients’ mad requests, going great lengths to enable their delusions, including kitting out the entire staff in Nazi Gestapo get ups, much to Frankie Reno (Jason Miller), Kane’s second in command’s distress, it seems Kane himself may not be who he says he is, and may well be as mad as the rest of them.

A quasi-theological confrontation with the same old problems of good and evil in a madhouse carnivalesque of slapstick reversals, (the castle almost a twisted M*A*S*H*-like sitcom setting) – sane and the insane, sacred and the profane, authority and anarchy – The Ninth Configuration is set against a backdrop of mid-century paranoia: The Manhattan Project, Operation Paperclip, MKULTRA, Vietnam and the like, and beneath its surface funny-business leaves a truly painful sense of the unresolved, the same old story, morality undigesting in the gut.

5. Kamikaze 1989 (1982)

From director Wolf Gremm, based on Per Wahlöö’s 1964 novel Murder on the Thirty-First Floor comes Kamikaze 1989’s anarchic pop-art pastiche & parody of dystopian science fiction, starring Germany’s outlaw auteur himself Rainer Werner Fassbinder swaggering around in a leopard print bathrobe just months before his death.

Set in an Orwellian state unified beneath a single centralized institute of propaganda the struggle against totalitarianism is reframed as a battle between hegemonic media and underground artists, and namely the rogue satirist and culture-jammer Krysmopompas who may or may not be related to a series of bombings Fassbinder’s Lt. Jansen is assigned to investigate, slinging his gun through the eccentric nooks and crannies of an anonymous ultra modern West Germany of identical housing blocks and endless office complexes.

A delirious murder-mystery leading inevitably centreward, into the heart and the high offices of power – its elaborate detective plotting amounting to little more than the necessary procedure leading Fassbinder through a string of pulp setpieces and absurdist interviews toward an end we all already know. There is a little of John Waters in its sometimes eclectic DIY feel, and a lot of Godard’s Alphaville in this, reborn under heavy 1980’s irony and psychotronic neon.