6. Blow-Up (1966)

Something which can be said about Kubrick as a director, is the fact he always managed to create timeless pictures. From Paths of Glory, and 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut — every film bearing his name felt (and still feels) ahead of its time. Kubrick’s radical style granted him a fair share of detractors who couldn’t help but stare in bewilderment at his unorthodox masterpieces. Needless to say, time has been kind to his work and former doubters have in turn become fervid admirers.

A fellow auteur who also had to bear with the burden of his revolutionary talent was Michelangelo Antonioni. Originally chastised by so-called purist critics who scorned his plotless narratives, the Italian soon became the poster boy for the European arthouse fare with a trilogy of melancholic dramas (the second entry of which — La Notte — made Kubrick’s first and only known top ten list). These films scratched an itch especially among young viewers in the way they dealt with urban malaise, social alienation and unrequited love.

Antonioni continued to dissect the generational ennui of his time with Blow-Up — a brilliant, subversive neo-noir that weaves through the fashion scene of London through the prying eyes of a photographer who stumbles upon a murder scene during one of his photo-shoots.

7. Deliverance (1972)

In most of Kubrick’s movies, the destination takes a back seat to the journey, where through a series of trials and tribulations his characters inherently evolve or show their true colors.

Sometimes, the journey literally changes the status of these individuals — Spartacus goes from a Thracian gladiator to a messianic leader and liberator of slaves, whereas humble Irish peasant Redmond Barry marries his way into the English nobility, becoming Barry Lyndon. In other cases, the journey reshapes them introspectively by shaking their complete worldview. Take for example David Bowman in 2001, who’s forced to reassess mankind’s place in the cosmos as much as his own morbid curiosity. Private Joker goes through a similar spiritual pilgrimage in Full Metal Jacket — going from a wisecracking, naive recruit to a dejected trooper with a thousand-yard stare.

Deliverance is a textbook example of characterization through setting. Four men embark on a canoeing expedition through the wilderness of the Cahula River, where their resolve is tested as they come to terms with nature’s prowess and confront their inner demons. The perpetual conflict between man and nature has been done to death in fiction, but arguably never as palpable and unapologetically as in this John Boorman’s film.

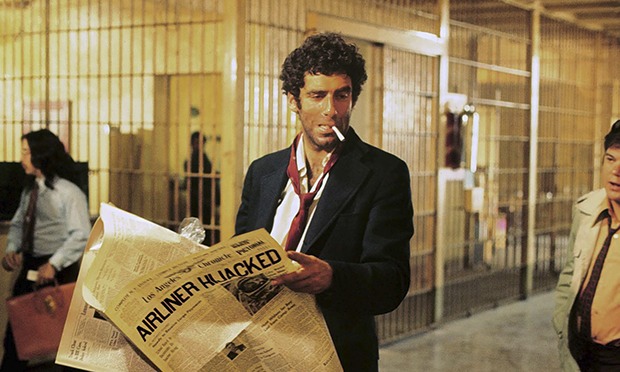

8. The Long Goodbye (1973)

Some of the traits that came with Kubrick’s genius were that of a borderline-obsessive technician — a certified workaholic who ruled each of his productions with an iron fist and was notoriously demanding with his crew. Through the years, plenty of stories have come out chronicling his stern modus operandi — painting the image of a perfectionist who held everyone around him to the same standard of excellence he applied to himself.

In that respect, Robert Altman might have very well been the ultimate anti-Kubrick — an actor-friendly director who heavily relied on improvisation and his guts to make decisions on the fly (and who didn’t mind relegating duties either). The only time both legends ran into each other in London left us with a funny exchange that perfectly captures their clashing philosophies. During their brief encounter, Kubrick inquired about a particular zoom lens shot featured in Altman’s latest film, wondering if the director had done it himself. “No”, Altman replied, “my cinematographer does that.” To which Kubrick — ever the control freak — countered: “And you trust him?”.

9. House of Games (1987)

Dialogue is not the first attribute that comes to mind when talking about someone like Kubrick who practically reinvented cinema and pushed its frontier as a visual medium further than anyone else before him. However, as is the case with any other worthy director to ever pick up a camera, he sure knew how to employ language to thrust the viewer into the character’s headspace and bring his point across.

Dialogue is precisely what sets House of Games apart. Written and directed by David Mamet, the film stays true to his signature style of rapid-fire banter, deadpan deliveries and naturalistic feel that he forged throughout his years as a screenwriter. Every line of dialogue is deliberately placed and carefully delivered a certain way, always hinting at misdirection or a hidden, deeper meaning. This further amplifies the film’s labyrinthine plot that sees a jaded psychiatrist venture into the wretched underworld of hustlers and con men. There’s a morbid fascination that gets a hold of the main character, mirroring Bill Harford in Eyes Wide Shut as two individuals too curious for their own good.

10. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Any parallel between Stanley Kubrick and Quentin Tarantino ends at their sheer cultural impact. Because when one pitches their work against each other, they’re like chalk and cheese. One was a complete master of form — the golden standard of visual language — capable of conveying a plethora of emotions without muttering a word. The other took the world by storm with a derivative style bursting with self-awareness that favored characterization and snappy dialogue over any set of conventional narrative rules.

Any attempt at adding something new to the discourse regarding a cultural juggernaut like Pulp Fiction seems like a vain exercise. After all, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more over-analyzed and debated piece of fiction — let alone film — released in the past thirty years. We do know for a fact that Kubrick liked it and thought it was ‘slick’, according to Frederic Raphael — co-writer of Eyes Wide Shut screenplay.

It seems as though the praise may not have been reciprocal. If anything, Tarantino is not someone to ever bite his tongue, even when passing judgement on some of the biggest names in film history. Although he’s repeatedly gushed over A Clockwork Orange — which boasts in his opinion one of the most exhilarating openings in cinema — he’s been overall dismissive of Kubrick, accusing him of being too emotionally distant for his taste. One can only wonder what he thinks of his own work.