Extraterrestrial encounters have always been a fascination of science-fiction, visions of strange life forms evolved to the conditions of different worlds, or to technological powers far beyond our own. On film one thinks first of the alien invasion, the saucer fleet of War of the Worlds (1953) and the looming mothership of Independence Day (1996), the militaristic nightmare parodied in Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks (1996), and second of the alien as a killer beast beyond reason, from the countless B-shockers of the 1950’s like The Blob (1958), John McTiernan’s sport-hunting Predator (1987), and probably most of all the xenomorph of Ridley Scott’s 1979 classic Alien.

But alongside this science fictional fascination with extraterrestrial beings there has long been a tradition of scientific interest, theory, speculation, attempts to communicate, and of course, sightings — the whole phenomenon of the UFO. Saucers, lights, strange bodies in the sky have been sighted and recorded all through modern history and as early as the 19th century the notion of alien crafts explaining these aerial phenomena entered the wider culture. And rather than a superstition put to rest with the development of aerospatial technology, sightings of UFOs, their being tied to factual, physical phenomena, and credit to extraterrestrial life has only accelerated since the second world war, from the earliest accounts of “ghost rockets” and “foo fighters” throwing off early radar, to the high profile encounter claims at Roswell and Socorro, New Mexico, Rendlesham Forest, among countless others. UFOlogy was born. Across military, scientific, and hobbyist communities, groups devoted to the investigation of UFOs sprung up, notoriously the American projects Sign (1947), Grudge (1949), Blue Book (1952-70), AATIP (2007-2012), and the ongoing radio monitoring efforts of SETI, since 1960’s Project Ozma.

The UFO becomes for the wider public a kind of rorschach test, yielding significances scientific, political, religious, and psychological. The films that follow are a set of science fiction films that play on this other side of the extraterrestrial in our cultural consciousness, and though not all fact-based, many draw upon the accounts of UFO encounters as told by their witnesses, and all embrace the ambiguities, centrality of skepticism, and investigative perspective of UFOlogy, playing these themes across a number of dramatic forms and ends – subgenres of the UFO film.

1. Communion (1989)

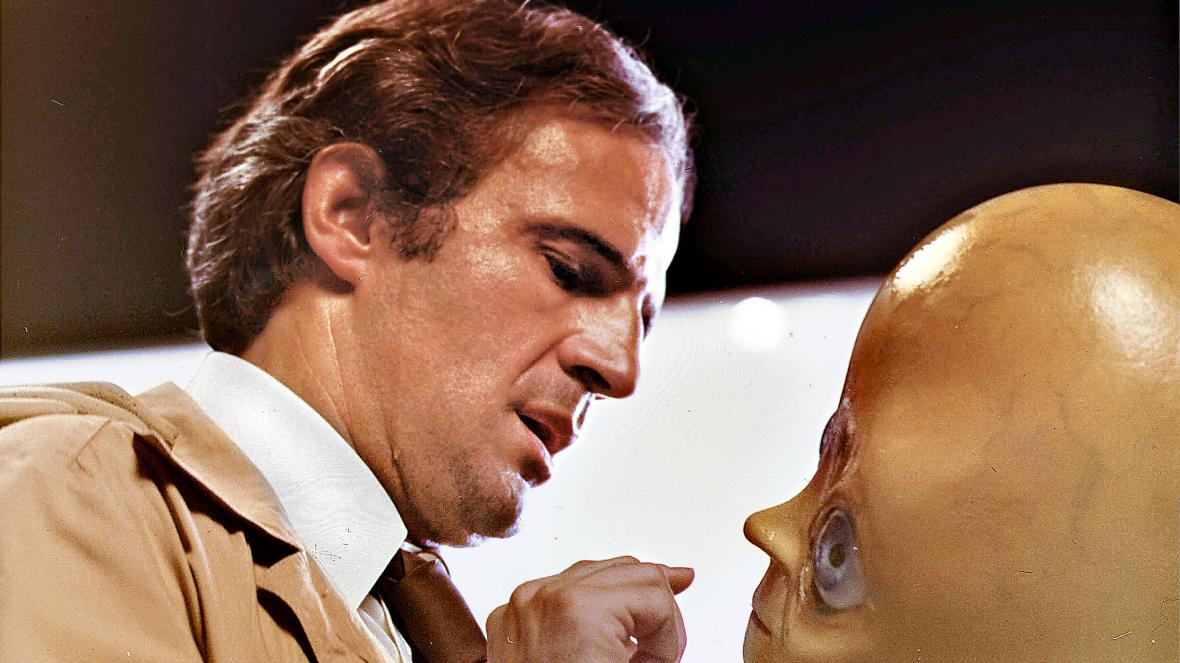

Based on the 1987 best-selling abduction account of Whitley Strieber, Communion from director Phillipe Mora tells Strieber’s story of abduction from his upstate New York cabin on December 26, 1985, and the psychological dislocation that followed for Strieber, a self-professed skeptic to the day of his abduction.

Drawing on a nuanced character study of one man’s encounter with the irreconcilable, Mora also directs a bold, sometimes comic depiction of classic and tabloid extraterrestrial imagery – greys with big heads and big eyes, and blinding blue lights deep in rural seclusion. The film carries a mad manic energy thanks to Christopher Walken whose outsize performance portrays not only the psychological unravelling of a man plagued by post-traumatic paranoia but also the ecstasies of a man who has found himself privileged to see beyond the realm of ordinary life, perhaps, Strieber speculates, into another dimension.

And it is both this ecstasy and the apparent replication of his experience in his young son Andrew that drives Strieber to try and face his fear in therapy and re-abduction – whatever that means – and form a healthy relationship with these visitors whether they be anomalies extraterrestrial or purely psychological.

And with a soft-fuzz glow to the cinematography, a sailing electric score by Eric Clapton, and the commercial surrealism of the alien imagery Communion with its excellent source material and lead performance marks a high point of artistic achievement within the UFO film.

2. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Steven Spielberg’s modern classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind – taking its name from the classification of encounter with a manned extraterrestrial craft from Blue Book’s J. Allen Hynek – set a standard for the cinematic UFO film, both in the imagery of its encounters, and in the procedural way the film tracks them across reactions civilian and governmental in a grand sweeping portrait of first contact as both a cause for military cover-up and a unifying event among the planet Earth.

Split primarily between the middle American UFO witness Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), and the globetrotting Dr. Claude Lacombe (based on UFOlogist Jacques Vallee and played by Francois Truffaut) who has been tracking reports of UFO activity from the United States to Northern India and Mongolia, the film arrives at the iconic Devils Tower, Wyoming, where an extraterrestrial landing is anticipated by a coalition of world governments.

What sets Close Encounters apart from many of the large scale UFO films to follow in its path is the essentially optimistic outlook it has on alien contact, and the aliens’ relationship with earth being one offering peace, and peaceable exchange – unlike the paranoid warmongering of films like Independence Day which hijack and repurpose its images – the UFO towering over human civilization as display of military power and a threat.

And with its use of music as the universal language, the one by which the aliens contact humanity, the film echoes human efforts to broadcast music out to any extraterrestrial intelligences that might be listening.

3. The UFO Incident (1975)

Richard A. Colla’s The UFO Incident is a made-for-TV treatment of the September 19th, 1961 New Hampshire incident, or the abduction of Barney and Betty Hill. Their story is that of a couple experiencing lost time (a blackout of 2hrs & 35 minutes) and later recollections of their hypnosis and abduction by a UFO out on the highway, being led aboard by its extraterrestrial crew and experimented upon. Still later Betty Hill would produce a star map she claimed the crew to have shown her, indicating their home, which would later be compared to the then-undiscovered Zeta Reticuli star system.

Playing to its low-budget limitations the film dramatizes the transcripts of Barney and Betty Hill’s post-abduction interview sessions with psychologist Dr. Benjamin Simon, both under regressive hypnotherapy and not, framing the story in a fact-based authenticity that conveys the Hill’s story on film in the exact ambiguity with which it was relayed to the world.

The film recreates the night of these events as they are recollected in disorienting cutaways, and intersperses scenes from their somewhat strained existence as an interracial couple in 1961 America – something factored into the final clinical consensus that their abduction had been a shared hallucination brought on by the stresses of racial discrimination.

The casting is great, with James Earl Jones as Barney, stoic to the minute of his final recollection, and Estelle Parsons as Betty, playing a convincing mix of terrified bewilderment and an endearing sympathy toward her perceived abductors.

4. The McPherson Tape (1989)

From independent director Dean Alioto, The McPherson Tape was a found footage horror predating the oft cited genre originator The Blair Witch Project (1999) by a decade, not only predicting the video era’s advent of found footage horror generally, The McPherson Tape also establishes a popular UFO film form that would persist into the 2010’s with Paranormal Activity’s found footage revival and films like The Fourth Kind (2009), Skinwalker Ranch (2013), and Alien Abduction (2014).

With its conceit as the videotape of a family birthday dinner at a remote Connecticut cabin on October 8, 1983, and use of non professional actors, who neither look nor sound like coached movie people, the film achieves a convincing naturalism and atmosphere of tension as the viewer, knowing where the film leads ahead of its characters, anticipates the interruption of alien intruders. And while the film’s cheesy costuming and effects sort of blows its authenticity when they do arrive, the film maintains a frantic energy and dramatic investment to the end of its brief runtime.

A bit of a cult thing in 1989, the film made its rounds on a hoax hype, being sold, much like the later Blair Witch Project (1999) as a genuine artifact, another trend repeated by the UFO film, and perhaps most notoriously with the circulation of Spyros Melaris’ hoax tape Alien Autopsy (1995) that purported to be footage leaked from the Fort Worth army air base.

Following the film’s cult success and a 90’s revival in UFO interest the director was asked to remake the film for TV in 1998 with Alien Abduction: Incident in Lake County. Essentially a retread, Alioto’s second effort includes mockumentary interviews with various analysts of the footage presented between commercial breaks, attempting to hoax a new demographic with its Fact or Fiction? disguise, but comes off – ironic for its larger budget – a little more stagey, and loses some of the indie charm and ingenuity of the original horror-hoax.

5. Roswell (1994)

Roswell, the ur-myth of American UFOlogy is given a dramatization as an adaptation of Kevin D. Randle and Donald. R. Schmitt’s book UFO Crash at Roswell that examines the testimonies of the rancher William Brazel who discovered the craft and the first responder Col. Jesse Marcel, and argues the legitimacy of the craft’s extraterrestrial nature, and an intentional cover-up on the part of the US military in declaring the craft a weather balloon. Their account also purports the recovery of a living being known as EBE from the craft and held in the now infamous Area 51, a part of the Roswell myth corroborated by USAF Col. Philip J. Corso and ex-air force conspiracy theorist Bill Cooper.

Little dry for its focus on exposition, Roswell is a decent production of the Roswell story from the perspective of an ageing Col. Marcel (Kyle Maclachlan, likely cast for his role as Agent Cooper on the paranormal and sometimes UFO-related TV series Twin Peaks) tracking down different eyewitnesses and cobbling together a possible story out of retrospect and hearsay – allowing for the film’s inclusion of all the exciting bits (including a great scene of the ailing EBE sick in an Area 51 bed) without surrendering a skepticism or making any final claims to truth. Alongside Maclachlan and a long list of minor roles is co-star Martin Sheen as ‘Townsend’, a fictional informant character who gives voice to the film’s final position: Nobody is going to take you seriously, not without proof, not without hard evidence.