6. Bronco Billy (1980)

Just seven years after the brutal savagery of “High Plains Drifter,” Eastwood mined once again his cinematic persona for an infinitely more gentle and light-hearted examination of western tropes in his delightful modern cowboy tale “Bronco Billy.”

Not a traditional western by any stretch (I imagine some would even contend with its inclusion in this list), the film is nevertheless very much of a piece with Eastwood’s other, more celebrated incursions into the genre as a director, because it has the same interest in western iconography as artifice, a social and historical construction that conceals darker depths. That is more or less a recurring theme in all of the westerns he directed, but it’s never been more literal than in “Bronco Billy,” in which the main characters use their jobs as part of an Old West travelling circus show as an opportunity to forge new identities for themselves within the archetypes of the western, from the noble Indian to the hero cowboy – the latter played, naturally, by Eastwood himself.

It’s one of his best performances, that sees Eastwood willing to gently poke fun at his macho posturing, frequently positioning Billy as a buffoon – a humorous and good-natured turn that proves he’s a much more self-aware performer than many give him credit for.

It’s a funny and heartwarming movie that is unfortunately forgotten in the shadow of Eastwood’s more monolithic works, despite being one of his very finest directorial efforts.

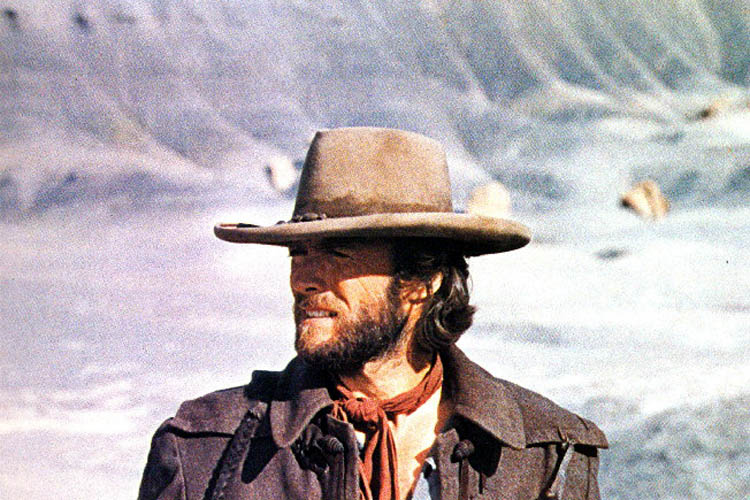

5. The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

Eastwood had proven himself to be a real filmmaker very early on – from the already mentioned and canon-accepted “High Plains Drifter” to the wonderful but sinfully underseen romantic drama “Breezy” – with films that demonstrated that he wasn’t just a shallow movie star cosplaying as a director, but a real artist with blossoming talent behind the camera.

Even then, it could be argued that Eastwood’s place in the canon as one of America’s greatest and most celebrated auteurs only started with “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” his second western as a director. Good as it is, “High Plains Drifter” is still too indebted to (a generous term, perhaps, for “derivative of”) other movies and filmmakers, whereas “Josey Wales” is distinctively Eastwood-esque, the first time he honed in his moody and lyrical style, unlocking the stylistic and thematic predilections he would go on to explore for the entire rest of his career – particularly his later, post-“Unforgiven” work.

Now, it must be mentioned that this was originally supposed to be directed by Philip Kaufman (the credited screenwriter), who was responsible for the entire pre-production work and did shoot some of it before being fired by Eastwood due to creative differences. So, undoubtedly, it can’t be said that this was a purely Eastwood creation all the way through, and it differs from his early work in some key ways that demonstrate Kaufman’s hand. But it’s most interesting to notice where Eastwood did put his stamp and what that reveals about him as a filmmaker.

“The Outlaw Josey Wales” is basically the most comprehensive and accessible document of Eastwood’s much debated ideology. The book the movie was based on was written by a literal KKK member and the script was adapted by a Hollywood liberal – a combination that promises ideological whiplash, but Eastwoods subverts both points of view by creating his libertarian dream. He took that and made a movie about people of different backgrounds coming together under the common goal of defeating an all evil government. That’s Eastwood in a nutshell: he’s inherently distrustful of institutions, but he loves people and individuals.

4. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

As Andre Bazin said in one of his seminal essays, the inception of the western as a genre dates back to the very creation of cinema itself: one immediately follows the other. It’s something that cannot be said for any other genre: comedy, drama (tragedy), horror, sci-fi; all have rich histories in literature and theater long before the Lumiére brothers ever filmed that train. The western is the only genre invented solely for the cinema.

That being said, there’s not one single movie or director that can be credited with starting the genre; it was an organic and collective movement that gradually spread until it became a staple of the industry. The Spaghetti Western, however, has one bonafide founding father: Sergio Leone.

“A Fistful of Dollars” wasn’t technically the first European or even Italian western ever made, but before Leone, those movies were just comedies or low budget B-movies that failed to achieve expressive success. This was the movie in which Leone birthed the entire stylistically handbook for the next 15 years of Spaghetti Westerns (not to mention the countless post-1970s filmmakers who are still inspired by the movement), like the extreme close-ups juxtaposed with expansive wide shot vistas, operatic crescendos in drama, violence and, of course, the Morricone soundscape.

Leone’s unique vision was ecstatic and thrilling from the get-go, but “A Fistful of Dollars” is downright modest compared to the levels he would reach just a few years later; it still feels like a prelude, albeit an excellent one, of greater things to come. And speaking of which…

3. For a Few Dollars More (1965)

There are many considerable leaps in quality from the first movie in the Dollars Trilogy to this one, “For a Few Dollars More”: Leone’s mastery of composition, pacing, and movement within the frame seems to have been supernaturally enhanced in the single year between this and his western debut (or, more likely, the higher budget allowed him to execute the visual brilliance he was always capable of). But most importantly, this is the one where Lee Van Cleef comes into the game.

Van Cleef spent the majority of his career playing bit parts in B-westerns, the kind of “Henchman Number 2” that gets efficiently dispatched by the hero with a single bullet and never thought of again. His rise to prominence as a star in his own right only came more than a decade later, courtesy of Leone, who cast him in this movie as the only bounty hunter in the old west who could rival the Man With No Name.

That’s the making of what is arguably the greatest buddy movie of all time, as Eastwood and Van Cleef’s character’s begrudging respect for one another is only equaled by their mutual mistrust. That relationship forms the basis of the propulsive narrative; their attempts to outwit and double-cross each other only to find themselves being forced to collaborate again and again makes for the best plotted story Leone ever did (plot wasn’t one of the filmmaker’s many gifts).

Lee Van Cleef is not as widely well-known as Eastwood or even John Wayne, the two most iconic cowboys of cinema, but there’s an argument to be made that no other actor in history ever wore the hat and holster better than him.

2. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Many critics and scholars have argued that “For a Few Dollars More” is the superior movie in the Dollars Trilogy: it has all the indelible imagery and sublime music that makes all of the movies classics, plus a tighter focus and little grace notes that are lacking in the other two. There’s a strong case for that argument, since, as said above, the movie truly is a masterpiece on every level. However, at the end of the day, even if it’s not the most overall perfect of the three, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is simply unbeatable.

The spaghetti, despite being a bastardized offspring of the original American genre, is now, stylistically, what most people think of when they hear the word “western.” Most likely than not, if a director is going to make a western today, they’ll be taking their cues from these Italian films of the ‘60s rather than the classics of John Ford or his contemporaries (look no further than Tarantino’s entire career, but especially “Kill Bill”‘ and his last three movies); even broad parodies of the genre will make fun of the dramatic duels, the twangy score and so on, elements that are distinctly from the spaghetti and not from the American tradition.

Every single one of these characteristics was distilled to their most mythical, elemental, and iconic in “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”: the archetypal nature of the characters (non-ironically suggested by the title itself), the way Leone stages and edits action (low angles of guns on holsters; extreme close-ups of faces and eyes; intercut with the expanse of the desert around), and, of course, the whistles, harmonicas and chants of Morricone’s score that have become the definitive sound of the cinematic Old West.

A monumental achievement that can’t be surpassed on its own terms; anybody who has attempted or will attempt a straight western after this is just chasing Leone’s shadow.

1. Unforgiven (1992)

The western to end all westerns.

If “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” is the apotheosis of the western golden age, then “Unforgiven” is the epitome of the revisionist western, which began roughly in the ‘70s when a new generation of filmmakers’ simultaneous adoration of the genre, aligned with their understanding of its questionable moral underpinnings, gave birth to some of the most rewarding, unique masterpieces of American cinema, such as “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” or “Heaven’s Gate.”

But even with numerous great movies from master filmmakers, there’s nothing in competition with the monumental achievement that is “Unforgiven,” either in Eastwood’s own oeuvre or, arguably, in the entirety of the western canon post-John Ford. Eastwood’s experience in the western as an actor, director, and also as a spectator (having been brought up in an era when the western was the most popular type of movie) gives him an understanding of the genre’s conventions (visual, narrative and thematic) that is only rivaled by film historians and the most hardcore cinephiles.

It’s such deep and ingrained knowledge that nobody before or since has been more skilled at finding new nuances the same old archetypes, of breathing sensibility into brutality, of subverting iconography so sophisticatedly. That includes his own image: as a performer, Eastwood has never been better, substituting his indestructible persona with a frail and vulnerable figure, plagued by regret and fear of relapsing into old habits. The whole cast, in fact, is superb, a masterclass in how to make every single character, no matter how inconsequential, feel like a complete human being.

And that’s the thing about “Unforgiven”: it is every bit as entertaining and thrilling as any other western (even the most traditionally “fun” ones), filled with all the surface pleasures one could ask for, featuring great, scenery-chewing performances; nerve-racking tension; beautiful cinematography; emotional character beats; and catharsis delivered via bloody shootouts. But with it, there’s also a depth of theme and deliberateness of subversion that is unparalleled.

There have been many westerns made since “Unforgiven,” but even the great ones are pointless, really – this closed the book on the genre. Everything else is an epilogue.