6. Lancelot du Lac (1974)

What appears at first a great and potentially disastrous departure for Bresson, the Arthurian legend explored in Lancelot du Lac turns out to be another strange match for Bresson’s style and a uniquely French take on these English heroes of French creation, portraying an episode of low morale and conflict in Camelot following great failures and losses in King Arthur’s (Vladimir Antolek-Oresek) search for the holy grail, preceding Perceval’s holy vision.

There is a lot made of the anti-heroics of this film and its critique of chivalry but Bresson also seems to find a great vitality in the formal symbolism of the chivalric tradition, and a perfect fit for his wholly external style, where a sword means something completely different held at this or that angle. The objects of chivalry are fetish – the swords, the standards, the armor – and the camera understands this. Sound is key too – there are maybe no images associated to the film so strongly as are the sounds of the knights’ armor, the sense of presence and weight they bring to every movement. If Bresson trains his eye on the round table at its lowest this seems less in reproach of the knights than a desire to study them at the ground-levels of conflict and conduct as quasi-historical and human figures.

The knights themselves are perplexing figures, – Lancelot (Luc Simon) carries on an affair with the queen Guienevere (Laura Duke Condominas), and Gawain (Humber Balsan) and Mordred (Patrick Bernhard) have a cruelty in them that openly despises the weak – though no more so than in Chretien de Troyes’ originals, – which never made claims to purity or the simple exaltation of violence – and their strivings, though perplexed themselves, and dressed in the impossible grandeur of poetry, are as real as those of any of Bresson’s protagonists.

More than simple idealization or critique Bresson embraces both an earnest celebration of the heroic tradition – the knights’ discipline and virtue, the excitement of their tournament and their idealistic quest for the grail – and the bleak unromantic violence of their ultimate ends, creating an uncanny nihilism and sense of amoral absurdity strange to historical fantasy.

7. Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971)

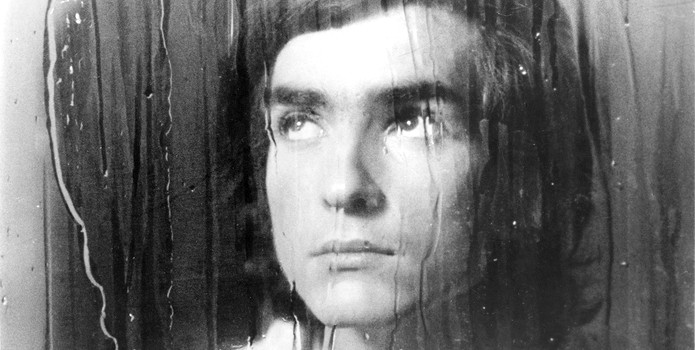

From Dostoyevsky’s White Nights, Four Nights of a Dreamer is a loosely autobiographical film of youth adrift in art and love set in a modern Left Bank, Paris. It is the story of a chance encounter between a young painter, Jacques (Guillaume des Forêts), and the seemingly suicidal woman, Marthe he helps up off a canal bridge one night (Isabelle Weingarten), and the brief relationship they entertain over the next four nights. Playing less like the high dramatics of Dostoyevsky, Four Nights of a Dreamer plays like a innocuous youthful episode from something Rohmer, a drama staged by characters in search of a drama.

In Jacques’ own words he is a nobody, he does nothing and sees no one. Actually his art school friends betray his artistic and intellectual ambitions. And when he is not painting he wanders the streets of Paris, searching faces in the crowd, speaking of other lives to his tape recorder. He lives as an alienated figure, a flaneur, like Michel a classically existentialist hero, but even as enjoying the freedoms and exemptions this way of life brings he longs for something more. He hitchhikes to nowhere, hides his work from prying eyes, and constantly falls in love with women in the street. It is not hard to picture the young painter Bresson in his shoes, especially as the narrator of Dostoyevsky’s White Nights hadn’t been a painter at all.

Marthe for her part longs for escape as well. Living with her overbearing mother and the boarder they share a house with, she remains stuck in the past, dreaming of the return of a past boarder (Maurice Monnoyer) she had an unrealized crush on, and is certain his return will be her redemption. She patiently waits nights on the canal bridge for him, unaware he has since already returned and made no motion to find her.

The meeting of Jacques and Marthe then should be an obvious romantic fulfillment, and yet the irony of the dreamer is that no reality is ever good enough for them. They have a way of taking lightly the serious, making serious the light, and constantly turning away from what’s in front of them. At once Bresson at his romantic and prosaic, Four Nights of a Dreamer is a lighthearted digression from his usual doom and self-seriousness.

8. The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

While it may not rival the power of Dreyer’s classic The Passion of Joan of Arc, Bresson’s The Trial of Joan of Arc has its own strength in its non-dramatic recitation of the trial’s actual transcript, and the facts as they were, and Joan of Arc (Florence Delay) at her own defense makes for one of the more interesting uses of Bresson’s pure cinema.

This historical perspective gives the film a distance from Joan’s convictions (where Dreyer’s, by way of its nightmarish aspect implicitly identifies itself with Joan and the righteousness of her beliefs) and reveals a new absurdity of the trial, political in nature yet draped in the guise of an extranational heresy, fixed against Joan from the start for simple military-political reasons, a drawn out ceremony of execution going through the motions of justice.

Instead, she is made a heretic for the way in which these convictions came to her, in voices and visions sanctioned by the official Church rules of epiphany, and beyond that, for her transgressions against the expectations of a woman, for carrying a sword, for wearing men’s clothes, and exercising will and authority in matters of spirit and war, and to this end denied the proper dignity of a military prisoner.

Her burning comes as a pointless and inevitable end to a pointless trial. Joan refuses to budge on her convictions, admirable perhaps, but no martyrdom here, a complete lack of dramatic payoff, horror or heroism. The stake is lit and the camera averts its gaze until in clearing smoke we see where Joan once was and is no longer.

9. The Devil, Probably (1977)

Some affinities to Four Nights a Dreamer, The Devil, Probably is Bresson’s second film on the alienation of bohemian youth, but where the dreamers of Four Nights were partially reconciled in art and romance, the youths of The Devil, Probably, in counterpoint or response, find themselves in a landscape of political upheaval and global crises and bowled over by a sense of dread and defeat. It is the story of a suicide, Charles (Antoine Monnier), working back from the end to live his last days and so the question of suicide hangs over the whole of the film.

Unlike Bresson’s other narratives of suicide the protagonist is not pushed down a path where no other option remains, instead, Charles lives a comfortable, hedonistic student existence, with plenty of opportunities for his future. Suicide then is not the final stage of decline, but an existential question considered as if objectively, as an answer to life’s many problems. Charles lacks the ideals and convictions of many of his peers, for whom a sense of impending doom has led to radical reactions in revolutionary politics, and environmental activism. Charles samples these alternatives – the state of politics and case of environmentalism only providing him with a greater reason to despair – as he does the salvations of sex, drugs, psychoanalysis, and religion, finding them all in the end insufficient.

Here Bresson works both his internal-individual narrative – Charles’ existential crisis like an atheistic return to Diary of a Country Priest, whose elaborate dialogues return in Charles’ nihilistic polemics as well – and the loose panoramic of Au Hasard turning his eye on all the intellectuals and dropouts of a Parisian post-68 generation. Though based on an original screenplay, critic Tony Pipolo suggested its origin in Dostoyevsky’s Demons, but for all the moralism of Dostoyevsky the Bresson of 1977 presents a world wherein suicide really is as logical a solution as any.

10. L’Argent (1983)

A strong contestant for Bresson’s crowning work, L’argent combines the internal narrative of his alienated and victimized individuals with the omniscient panoramic of Balthazar for an adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s “The Forged Bill”, which tracks the reverberations of a young boy’s entering a forged franc note into an economy of trickle-down sin, crime and punishment. Bresson’s style is never better than here, swift and tight, nearly dialogue-less, the camera never more knowing, each frame a meaningful irony pushing the machinations of fate forward, like a parable of modern life in Ikea instructions.

When the bourgeoise boy Lucien (Vincent Visterucci) cashes his forged note at the camera store the clerk, (Béatrice Tabourin) though suspicious, turns a blind eye, and soon at the behest of the store’s manager (Didier Baussy) passes the bill onto Yvon Targe, (Christian Patey) who services the store’s heating, and is later arrested using the bill at a restaurant. This begins Yvon’s decline into more and more desperate circumstances, turning to crime, losing his family, his freedom, and finally his soul. In its transmission the bill shows us a degraded world of crime and exploitation in the name of greed, fraud, theft, and murder, and the way money reduces our working, social, and familial lives to mutually deceptive and self-serving transactions.

There is a structural nature to the sin in L’argent, away from the simple misanthropy of his earlier films Bresson locates evil here in money itself, the money which stratifies society into haves and have-nots, victims and invulnerables. And yet the film maintains an old world moralism in the saintly figure of the old woman (Sylvie Van den Elsen) who in the film’s final act provides Yvon with care and shelter in charity, Christlike, irrespective of his crimes. Here in this refuge from the sin of the monetary system she lives a mostly self-sufficient life, yet open, and so vulnerable to the slightest predation of the outside world. Here Yvon Targe will fight the final battle for his spirit and make the final world on Bresson’s filmography.

An easy contender for Bresson’s ultimate artistic and philosophical statement, L’argent remains one of the greatest and most unique works of the French cinema. The sense of finality in this last film is accentuated by Bresson’s retiring after L’argent, apparently content that he had said at last what he had to say.