The haves and the have-nots is a story theme as old as time itself. For as long as humans have been living in society, there have been people with a lot and people with a little. Within the past few years, democratic socialism, the wealth gap, income inequality, and complex discussions about sex, gender, and race have become a focal point of our discourse.

It should follow suit, then, that many movies directly dealing with social inequality are cropping up. 2019 was the year of class warfare films, with a plethora of movies directly dealing with the consequences of marginalization. From Joker fighting Wall Street bankers to the Wolf of Wall Street himself duping the little guy, films are the perfect medium for communicating ideas around class-consciousness.

However, films dealing with these social inequalities are not relegated to the past decade. For more than a century, there has been a wide array of beautiful movies that have used creative storytelling techniques to spread a prescient message about the state of our economic systems and personal prejudices. Whether it’s a Russian parable about labor unions from the ’20s, or a cynical comedy about a telemarketer in over his head, social inequality is at the forefront of our cultural consciousness and is becoming equally important in the cinematic landscape.

The following list contains some of the most iconic, talked-about social inequality movies of recent years. However, it also has some older gems that paved the way for these cultural conversations to take place in film. Here are the 10 best movies about social inequality.

10. Us (2019)

Jordan Peel’s much-anticipated sophomore follow-up to his smash hit, Get Out, had gigantic shoes to fill. Coming fresh off a film that essentially defined 2017’s Trump-era politics while deftly balancing horror and comedy, Peele had to prove that he wasn’t just a one-trick pony.

Us follows Adelaide Wilson, her husband, and her two children as they revisit a summer home near the Santa Cruz beach in which a traumatic event in Adelaide’s childhood occurred. While her family settles in, Adelaide tries to shake the overbearing sense of dread she’s experiencing, only to have her fears confirmed when 4 masked strangers descend upon her home. But what starts as a standard home invasion thriller immediately takes a turn when the strangers are revealed to be the doppelgängers of each family member.

Us was a messy and unyielding film that failed to create the same cohesion and ultimate satisfaction of Get Out. But what it lacked in polish, it made up for in vicious energy. Us has an ambition that far surpassed anything Get Out was trying to do. It also featured a refreshed, enthusiastic director stretching his craftsman skills behind the camera with audacious setpieces and subtle breadcrumb clues designed for people who obsessively pour over every detail of a film.

Us creates a world where each human is tethered to another being, whose suffering helps maintain our material world. The metaphor is both strikingly clear and vague enough to stand in for multiple social systems we currently exist within. With a sense of elevated class warfare over the horizon and a horrifically brash inversion of Hands Across America, the film deftly illustrates the dangers of trying to mask or deny the suffering of others for the sake of the life we’ve maintained. It’s a foreboding warning to those who watch it: the suffering of others cannot be rationalized away, as those tethered to us will not remain silent.

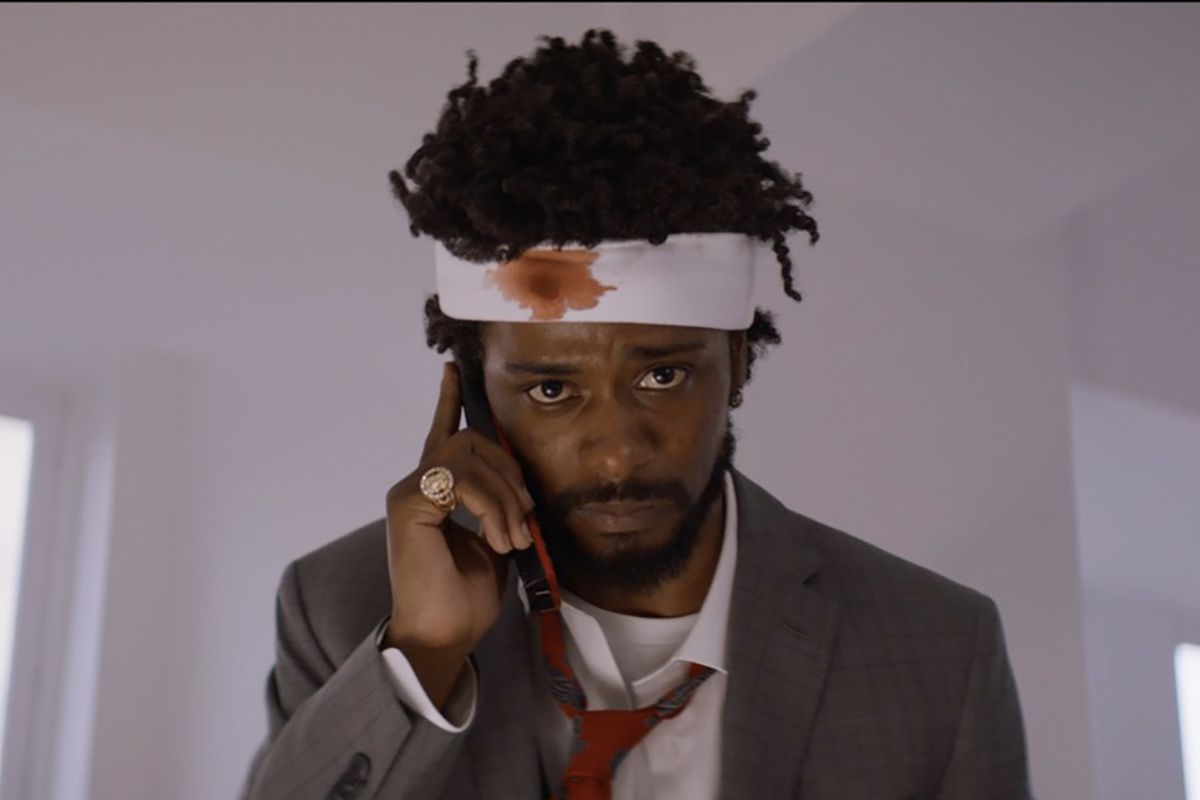

9. Sorry to Bother You (2018)

Sorry to Bother You is a dark comedy and directorial debut of Boots Riley. The movie takes the viewer through a cavalcade of off-kilter, but disturbingly plausible scenarios revolving around the modern-slavery system of Amazon work centers, soulless corporate jobs, picket line crossing, and a take on media manipulation via the news cycle so cynical, it has to be seen to be believed.

The film follows Cassius Green, a man living out a late-stage capitalist nightmare in an exaggerated version of Oakland. He quickly finds success in the telemarketing business by learning to code-switch. As he starts climbing the corporate ladder, he finds himself at a crossroads: does he cross the picket line and take the insane salary he’s being offered, or does he show solidarity with his co-workers, individuals in the same situation he was in mere days earlier?

Sorry to Bother You presents these ideas in a rapid-fire manner as it creates a true dystopia that feels both prescient and already manifested. It’s an incredibly confident entry from a first-time filmmaker that uses surrealism and nearly every tool in the filmmaker’s toolbox to create a postmodern masterpiece that boldly asks if it’s possible to succeed in our current system without our dignity and freedom being stripped away from us.

8. The Florida Project (2017)

The Florida Project paints a vivid and heartbreaking portrait of a single-parent family trapped in poverty. Director Sean Baker’s follow-up to Tangerine begins as a seemingly episodic story about a family living in a strip motel near Disney World. However, it quickly gives way to a tragic tale of desperation, and the cyclical choices that individuals must make when pushed into a corner.

The film follows six-year-old Moonee and her ragtag friends as they engage in mischief and run amuck, unsupervised in the Magic Castle hotel. Meanwhile, her mother struggles to maintain a stable life, living on the kind of budget where a late rent check could mean becoming homeless. To make ends meet, she resorts to a series of risky, calculated decisions including stealing Disney World passes, charging meals to guest’s rooms, and eventually prostitution.

On a technical level, the film is impeccably cast and shot with a deft touch and eye-popping colorization that makes the run-down motel feel nostalgic. The movie manages to avoid a lot of the pitfalls that many poverty films commit by focusing on Moonee’s perspective, highlighting the day-to-day activities she engages in.

The stark contrast between the joyful child perspective and the crushing cycles of poverty creates an engaging tapestry of moments that demand empathy and reckoning. Disney World casts a shadow over the motel and the film itself. It is foreboding and ever-present – both the focal point of Orlando and irrelevant to those without the means to engage with it.

7. Roma (2018)

Roma sees director Alfonso Caurón return to his roots with his first Spanish language film since Y tu mamá también, to great results. Receiving 10 Oscar nominations, and regarded as the best film of 2018, the film is a semi-autobiographical slice of life story about a live-in housekeeper’s experience during the Corpus Christi Massacre.

The film follows Cleodegaria “Cleo” Gutiérrez, a housemaid who works for an upper-middle-class family. During her time there, Cleo becomes pregnant and witnesses her employer’s marriage is falling apart. Protests, civil unrest, and the government-sanctioned massacre of student protests play out in the backdrop as Cleo comes to find solace in the family she works for, despite never truly belonging.

Cuarón employs a compelling technique in which political turmoil is contrasted with the mundane details of an intimately personal portrayal of a lower-class woman trying to live out her life amidst chaos. The film deftly balances the dynamics of the affluent vs. the privileged by using political unrest as a looming backdrop that heightens and emphasizes the vast amount of unabridged perspective between the two. Scripted with ambiguity and episodic structure, Roma sucks viewers in and is able to communicate large ideas with effortless simplicity.

6. Trainspotting (1996)

Trainspotting tells the story of generational poverty through the lens of an unemployed 20-something heroin addict. The film follows Renton, who after a particularly long binge on heroin, tries to clean himself up and “choose life”. But the allure of drugs and the opportunity to make money stand in his way.

Trainspotting is a deeply dark comedy, an energetic assault, filled to the brim with jaw-dropping moments so memorable, it’s easy to block out the class commentary until Renton finally stans up and screams about how terrible it is to be Scottish. Renton’s character, played masterfully by Ewan McGreggor, is propped up by a cast of fully realized characters, all suffering the same quandaries that he is: addiction, escapism, and the harsh realities of a life that doesn’t offer much by way of money, influence, or status.

The film forces viewers to ponder the nature of a lower-class lifestyle imbued with community. Getting out may be the goal, but not everyone can leave. To get ahead by way of turning on your friends is a harsh proposition in a class position where solidarity is all most people have. But Trainspotting challenges you to consider the cost and benefits of loyalty and freedom. To free yourself from your current life is to never return to that world, and in a world where redemption isn’t an option, the choice may not be as obvious as you think.