5. Watermelon Man (1970)

Watermelon Man is a bold and furious comedy that takes aim at the prejudices of white America by creating a racialized metamorphosis story that was far ahead of its time. The film is the first and only studio film by legendary filmmaker Mario Van Peebles. Though it was a financial success at the time, Peebles opted to not take Columbia’s three-picture deal, and immediately went into independently developing his follow-up Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song instead.

The film follows Jeff Gerber (played in whiteface by comedian Godfrey Cambridge), a racist white salesman who, without warning, wakes up one morning as a black man. After terrifying his wife, going through the stages of denial, and attempting to regain his whiteness by bathing milk, Jeff eventually goes out into the world as a black man and experiences a society that is hostile towards him.

Though the film rests in relative obscurity, often only noted as a precursor to Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, this incendiary comedy has aged remarkably well. The bizarre humor is balanced with a wave of righteous anger and poignancy as Jeff has to reorientate himself and reevaluate his place in a world that is dominated by whiteness. The journey he goes through elevates the film above the average role-reversal comedies that plagued the 2000s and delivers a razor-sharp indictment of discrimination that dictates the social order of the suburbs.

4. Strike! (1925)

Before shocking audiences with graphic violence and mastery of montage theory with his magnum opus, Battleship Potemkin, legendary director Sergei Eisenstein released Strike, one of the earliest tales of proletariat rebellion in film history. Strike is a Russian silent film from the ’20s that tells the story of a revolution among factory workers during the Russian Empire era and their eventual downfall.

Presented to the audience in 6 chapters, the film forgoes traditional narrative structure and characterization to present a detailed depiction of labor strikes as straightforwardly as possible. Boasting a memorable score and frenetic editing, Strike proved to be the testing ground for Eisenstein’s montage theory, culminating in a memorable final scene where cops on horses terrorize the workers while the film is crosscut with cattle being slaughtered.

Though Strike’s narrative is light on characters and interpersonal relationships, this frees up the film to get into the minutia of exactly how the system works. Despite this, the film is not dry and formless. It is an effective piece of propaganda that feels more modern than most films of the last century and is guaranteed to evoke an emotional response. The scene of upper management reading the worker’s reasonable demands and then using the letters to clean up spilled drinks remains as effective and angering as it was in 1925.

3. Parasite (2019)

Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite made history as the first South Korean film to win the Oscar for Best Picture. But the achievements of Parasite surpass awards; it is a film that is laser-focused in delivering white-hot fury at the barriers that insulate the people on top of the hill from the people who live at the sewer level. Frankly put, Parasite is the definitive class warfare movie.

The film follows The Kim Family – a family of four who lives in a cramped semi-basement and barely gets by. After establishing a series of odd jobs that manage to keep the family afloat, each member, one by one, takes various jobs at The Park Family’s house. The Park Family are near opposites of the Kims – they live carefree lives and conduct themselves in a friendly but frigid manner. The Kim’s familial connections are kept under wraps as they start to take over the house, eventually culminating in a war between the two families.

Parasite is an exercise in analyzing the casual cruelty of the rich and contrasting it with the crimes of necessity that those without the means to live comfortably must take. The results are exhilarating, equal parts hilarious and haunting as the Kim Family finds that no matter what they do, they will never truly fit into a world that was created to alienate them.

2. Billy Liar (1963)

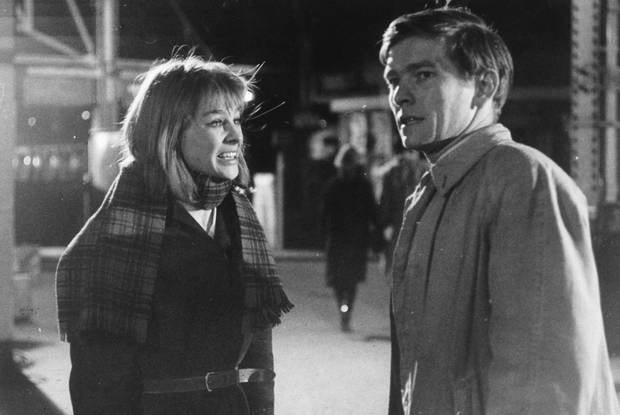

Due to its surrealist qualities, Billy Liar rests as an outlier within the British kitchen-sink realism movement. However, it is a key entry in the “angry man movie” genre and sets the stage for decades of films about disillusioned young men who wish for a better life. It serves as a precursor to everything from Clockwork Orange to Clerks and resonates with anyone who feels lost in a world they aren’t ready for.

Billy Liar follows a young man named Billy who is dissatisfied with his lower-middle-class life. Despite his lofty dreams of going to London to write comedy, he occupies his time juggling women, compulsively lying, and stealing from his job. To cope with his lot in life, Billy loses himself in constant fantasies, a vicious cycle that leaves him ill-equipped to survive in the modern world.

Billy’s journey, and his constant escapist fantasies, have aged impeccably well, illustrating the inertly tragic mindset many with lower economic status maintain: the temporarily embarrassed millionaire. Billy does not view himself as a member of the lower class. Rather, he views his current situation as an irritating roadblock, maintaining faith that his life as a rich and successful writer will begin as soon as he leaves for Paris, despite him barely having the tools to survive. But as his mother tells him, his troubles aren’t something he can merely leave behind.

1. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Bicycle Thieves is a heartbreaking tale of a man who is desperately trying to claw his way out of poverty, only to be thwarted at every turn. A heavy hitter in the Italian neorealist genre, the film features untrained actors and was entirely shot on location to preserve a realism that couldn’t be achieved on a studio set. The result is breathtaking, with long tracking shots to make you feel lost in Rome’s vastness, tight close-ups to heighten the feeling of desperation, and an unmatched soul-crushing mood that challenges you to not lose faith in the system.

Bicycle Thieves follows Antonio Ricci, a man who is desperate for a job to support his wife and child. He is offered a job, but with the caveat that he must own a bicycle. His wife decides to sell her family’s prized sheets to help him pay for the bike. On Antonio’s first day, his bike is stolen from him, forcing him and his son to wander the streets searching for the bike, or face financial devastation.

The core of the story is the relationship between a father and son, but the film’s broader effect is in the way it shows the cycle of poverty and the incredible lengths someone will go to escape these conditions. When Antonio reports his theft to the police, he is met with indifference. Yet, when he commits the same action in desperation, the whole city springs into action to stop and shame him, perfectly illustrating the bleak chaotic randomness that forces the individual to lose their dignity in the fight for survival. The Bicycle Theif stands as a classic look into the effects of poverty and asks viewers to ponder if they’d act differently in Antionio’s situation.