5. Hud (1963)

Paul Newman had the looks, charm, and charisma of a bigger-than-life movie star, but what’s most admirable about him as an artist, and what secured his legacy as one of the best American actors of all time, was his courage in taking morally complex roles that were in no way an easily digestible hero the audience could root for.

That is never more true than in “Hud,” Martin Ritt’s gorgeous neo-western, in which Newman plays a deeply unpleasant man. Selfish, violent, and largely unrepentant of his many mistakes, his titular character is never sympathetic, but always understandable; thanks to the nuanced, emotionally intelligent writing and Newman’s own raw performance, the movie paints a picture of a deeply troubled but ultimately irredeemable person undone by his own nature. It’s a wonderful character study, so austere, adult, and complex that it feels right at home with the New Hollywood movement, despite predating it by about six or seven years.

And the greatness of “Hud” extends to everything around Newman as well: not only is the rest of the cast terrific (particularly a vividly human, Oscar-winning turn by Patricia Neal), Ritt’s directs the hell out of it too, perfectly capturing a sense of melancholy and the quiet hopelessness of the vast landscape of the American desert – which has rarely looked better than in James Wong Howe’s magnificent, breathtakingly beautiful Panavision cinematography.

4. The Hustler (1961)

Another quintessential Newman anti-hero, of course (and what may very well be his signature character), is Eddie Felson, the titular hustler of this 1961 classic.

Along with Luke Jackson, Felson has become the definitive Newman role because it’s the one that served most perfectly as a vessel for all the actor’s strengths. As a man who uses his ample charm and bon vivant persona both as a tool in the con and also as a shield against the darker feelings he seeks to suppress, Newman employs his effortlessly cool demeanor to poke holes in that posturing, demonstrating the immense vulnerability lurking underneath the polished exterior.

It’s a wonderful performance, nuanced and lived in, but it’s not the sole attraction of “The Hustler,” which, much like “Hud,” is a film filled with a wonderful supporting cast (Piper Laurie and George C. Scott are great, but Jackie Gleason as Minnesota Fats is the true star, an iconic presence despite his limited screen time) and terrific pool scenes, a difficult sport to make cinematically interesting, but that director Robert Rossen and legendary editor Dede Allen shape into dynamic, endlessly compelling sequences.

3. The Color of Money (1986)

No doubt this choice will seem heretical to some, but, when comparing the two, it’s not inconceivable to say that, good as it may be, “The Hustler” is still slightly inferior to its belated sequel, “The Color of Money.”

It’s an unfair and unproductive comparison to begin with, of course, since the movies are continents apart, in every way: Rossen’s sturdy classicism is a far cry from Martin Scorsese’s kinetic stylization, and the plot (adapted from the book, but unmistakably shaped by screenwriter Richard Price) is a much more straightforward caper, an entertaining con-man story rather than a meditation on addiction, obsession, and failure like the first film.

The only throughline in both movies is Newman’s eternally magnetic presence, but everything else works as a standalone picture; a preference for one or the other really comes down to personal taste. And “The Color of Money” has many specific attractions to make its case: the central relationship between Felson and the new characters played by Tom Cruise and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio is arguably more dramatically compelling than anything in the original. Scorsese’s maniacal energy and aesthetic sophistication are as electrifying as ever, even on a job for hire like this. But, most importantly, this movie is simply a blast.

2. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Newman’s best films, as showcased by this list, varied equally between classically Hollywood populist filmmaking about mythical figures, perfect for his unmatched coolness and charisma; and somber dramas preoccupied with regular people, in which the actor showcased a depth of emotion and range of abilities rarely reached by his contemporaries.

The best representatives of these two sides of Newman occupy the top spots in this list and, as far as his movie star side goes, it simply doesn’t get any better than “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” As a western, George Roy Hill’s film is one of the best ever made; a entirely unique spin on the genre that is neither the elegiac tone of John Ford nor the operatic nature of Leone, veering closer to the relaxed hangout vibes of Howard Hawks, with its emphasis on the camaraderie between the characters.

But the film distinguishes itself from Hawks by the style, one that is more modern and playful than that master’s visual classicism; the different colour palettes of Conrad L. Hall’s terrific cinematography was a pioneer of many techniques that have since become staples of filmmaking.

And as a buddy movie, it’s unsurpassed: the chemistry between Newman and Robert Redford is so electric that the same creative team made a whole other movie around them just a few years later. But even then they couldn’t capture that lightning bottle that was “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

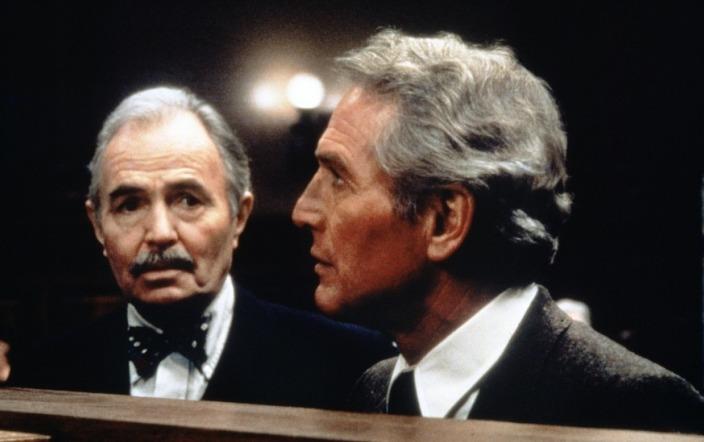

1. The Verdict (1982)

The triple threat of a Sidney Lumet, David Mamet and Paul Newman collaboration couldn’t possibly have been anything less than excellent, but “The Verdict” surpasses even the high bar set by the weight of such names.

One of the greatest American movies of the 1980s (though largely unsung in that regard), the film demonstrates the absolute best of these three essential artists, whose particular talents feed off each other to fabulous effect. Mamet’s writing refuses to sand down the core moral rot of the main character, which Newman admirably tackles head on with absolute honesty (he even fought the studio to keep in a scene in which he strikes a woman), making his redemption arc all the more impressively crafted.

Of course, the lived-in quality and powerful emotional honesty of Newman’s performance is owed entirely to Lumet’s fairly unique process (for Hollywood filmmaking, that is) of extensive rehearsal, from which all the performers create the core of their characters. It’s no coincidence that one of the constants throughout Lumet’s incredibly varied career is phenomenal performances, since he worked very hard to achieve that.

“The Verdict” is the defining late career masterpiece of Paul Newman’s career; the ultimate testament to his commitment in playing difficult roles that any other movie star of his stature would never go near. For comparison: Robert Redford was once attached to this movie and did everything in his power to sand down the alcoholism and womanizing of the character – precisely the elements Newman fought to highlight. A true artist, to the very end.