6. Captain Clegg (1962)

Although Hammer was best known for their horror films, Captain Clegg (1962) falls into one of studio’s more left-field sidelines: historical romances. Given their overseas reputation, and slim budgets, these tended to emphasise brutality over exciting action scenes, but Captain Clegg, directed by Peter Graham Scott, is a refreshing exception, being a swashbuckling adventure with a touch of christmassy ghost story.

In the late 1700s, reports of smuggling bring a squad of customs officers upon a village in the Romney Marshes, whose community is also being menaced by the legendary ‘Marsh Phantoms’. The squad’s leader Collier (Patrick Allen) is stonewalled at every turn by the townsfolk, led by the affable rector Dr. Blyss (Peter Cushing). The conspiracy of silence comes unravelled when one of Collier’s party (Milton Reid), a former shipmate of the infamous and allegedly dead pirate Clegg, appears to recognise Blyss, culminating in a brawl between the town and the authorities.

The film was released in the United States as Night Creatures, Hammer having pre-sold an unmade horror with that title to its distributor, but, despite occasional appearances by the Phantoms, this is among their more lighthearted films, filled with pleasantly irrelevant details and featuring Cushing at his most emollient, making it somewhat similar to the ‘little man’ comedies of Ealing Studios. It also benefits from having more ambiguous characters than was usual for Hammer, whose portrayal of good and evil tended to be simplistic.

7. The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975)

Upon its original release, The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975) failed to make much of an impression. The reasons for this may be conceptual, as its title seemed to promise one of two things: either Sherlock Holmes has a secret, bumbling brother, or a bumbling Sherlock has stolen the thunder from an overlooked smarter brother. It was probably meant to be the former, but Gene Wilder, in his directorial debut, chose to play Sigerson Holmes as a romantic hero rather than just a clown, and so it ends up being neither. Instead it is an endearing throwback to classic swashbucklers.

In Victorian London, a piece of McGuffin paper gets stolen from the British government, so Sherlock covertly enlists his younger brother – a dandyish fencing enthusiast – to track it down as a decoy for the thieves (much like his use of Watson in certain Conan Doyle stories). Along the way there are music hall numbers performed by Madeleine Kahn and action set pieces straight out of a matinée serial. A supporting case of diminutive eccentrics includes Marty Feldman as Sigerson’s helper and Leo McKern as Moriarty.

During this decade it was fashionable to approach the Holmes mythos in terms of revisionism (The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, 1970), postmodernism (They Might Be Giants, 1971; The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, 1976), or outright parody (The Hound of the Baskervilles, 1978), but Wilder’s use of the character is more affectionately traditional, even romantic. As with so many swashbucklers, the story owes a little to Prisoner of Zenda, with Sigerson, often mistaken for Sherlock, confoundedly embroiled in high affairs of state, and getting berated for it by his nemesis during their final duel: “It’s very difficult to be a hero in real life.”

8. Robin and Marian (1976)

Director Richard Lester once claimed, “I’m certainly not a romantic but I’m not anti-romantic. What I am is desperately anti-sentimental, anti-nostalgic for the past.” He demonstrated this with a string of uniquely sardonic swashbucklers during the 70s, beginning with his brilliant, bawdy adaptation of The Three Musketeers (1973-74), followed by the cynical black comedy Royal Flash (1975), concluding with the wistful Robin and Marian (1976).

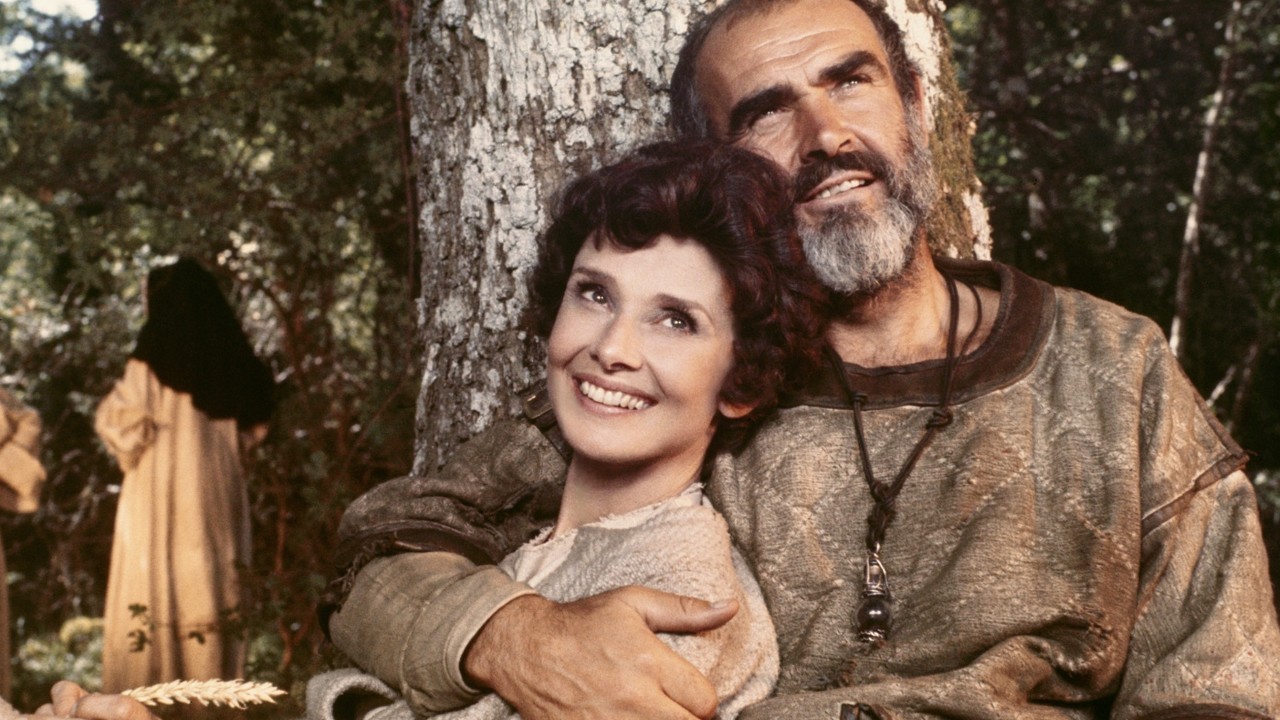

Originally titled ‘The Death of Robin Hood’, the story sees middle-aged Robin (Sean Connery) and Little John (Nicol Williamson) returning to England from the Crusade where they meet up with old comrades, including Marian (Audrey Hepburn), who has become a nun. The joy of their reunion is tempered with regret, however, as it soon becomes apparent Marian is suicidal and Robin has a death wish. Sensing they have both reached the end of their lives, they have one final showdown with the Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw) before bowing out.

To call this film a swashbuckler feels odd but it is difficult to describe in any other way. Certain aspects are gritty, including the more realistic portrayal of the Crusade as a genocide. Elsewhere, it mixes the slapstick violence of The Three Musketeers with sensitivity. This tonal dilemma could explain why Lester was reportedly unhappy with John Barry’s sweeping score, having previously rejected a more subdued one by Michel Legrand. What’s more, because several cast members were tax exiles, the film was shot in sunny Spain rather than England, giving it a sense of fanciful unreality not unlike The Adventures of Robin Hood, making it possible to imagine we have returned to that same universe once the entropy has set in. It also has a touch of warm self-awareness in the moment Robin meets Marian again for the first time, since it was also the first time audiences had seen Hepburn in almost a decade. Lester may have intended something bleaker, but the result is an autumnal variation on swashbuckling romances.

9. The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Swashbucklers have long been an influence upon manga creators and vice versa. Osamu Tezuka borrowed freely from Errol Flynn movies for his anime fantasy series Princess Knight (1967-68), whilst Jacques Demy’s historical black comedy Lady Oscar (1975) was adapted from Ryoko Ikeda’s manga The Rose of Versailles (1972-73), but the romantic action-adventure formula was effortlessly replicated in anime form with The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), debut feature of Hayao Miyazaki.

In a fictitious, Ruritania-style country, master cat burglar Arsène Lupin III stumbles across a plot by the fiendish lord of an enormous castle to forcibly wed a princess, in the hope of making himself king and uncovering the lost treasure of her ancestors. With the unwitting assistance of his Interpol pursuers, Lupin nonchalantly determines to rescue the princess and defeat a tyrant.

Drawing upon the gravity-defying fixations of France’s cinéma fantastique movement, as well as Paul Grimault’s great animated fairytale The King and the Mockingbird (1952), Miyazaki demonstrated with this film how his medium’s heightened energy levels made it the perfect fit for swashbuckling storytelling. The chivalrous portrayal of Lupin, originally an amoral womaniser, proved controversial with his creator, but resulted in a film as transportive as its castle’s dreamlike architecture.

10. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

It is widely agreed that the true spiritual precursors to Star Wars (1977) were The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk, though a key element of the swashbuckling formula is heroes driven by weighty motivations, swiftly resolved through improbably simple solutions. In Star Wars, the murder of one’s family or destruction of a home-world are instantly forgotten about, making its escapism more infantile than romantic. The Empire Strikes Back (1980) improved upon this, but with its slow, meandering plot, it is more operatic than swashbuckling. A truer reflection of the genre’s sensibility in the era’s sci-fi/fantasy boom can be found in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982).

In the 23rd century, ageing explorer Captain Kirk (William Shatner) retakes command of his old ship, just in time to find himself pursued to the death by escaped war criminal Khan (Ricardo Montalban), whose crew he marooned many years before. After an epic chase, Kirk outmanoeuvres his nemesis, but not without a great personal loss, thus earning the new lease of life he has yearned for.

Director Nicholas Meyer drew more upon C.S. Forester’s Hornblower novels than from the original television series. Produced for roughly a third the cost of its sterile predecessor The Motion Picture (1979), the emphasis upon liveliness and bravado is infectiously entertaining, with cheap and cheerful production values including a stirring colour palette of burnt reds and ochres, as if the future had been preserved in aspic. The acting may be hammy and even secondary characters cannot die without speechifying, but such broad strokes serve to remind you that its own brand of costumed frippery is not to be taken seriously except as romantic adventure, a vibe it evokes so perfectly that later films in the series failed to recapture it.