There’s a very important principle in cinema that most of the people who work in movies, or who seriously studies the craft, understand, but that somewhat eludes the casual viewer: a good screenplay is meaningless in the face of bad execution.

Meaning, having a great story is far from enough to secure an actual great finished film; the power of a picture is almost completely dependent on a filmmaker’s skill with cinematic language – a narrative can only be as compelling as it’s director is talented.

This is a fundamental truth of any genre, but it’s most evident with horror, in which no amount of intelligent, competent writing can compensate for the lack of a supreme element of terror: atmosphere. After all, that chill in your spine that only the best horror movies can cause exists from the cumulative effect of a well-constructed atmosphere.

With that in mind, let’s celebrate the horror films that did it the best; the ones with an atmosphere so indelible that no self-respecting cinephile could ever banish their hellish images from their minds.

15. Cure (1997)

The fundamental feeling any horror movie should evoke is dread. Of course, this is an extremely fluid genre in which many tones can coexist – there’s space in horror for very serious films and also straight up comedies. But fundamentally, even the lightest entries need, on some level, to provoke a sense of discomfort and tension in the viewer – this is the basis upon which horror is constructed.

In that way, there are few horror movies more effective than Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Cure,” a film built entirely upon the concept of an existential ennui so dreadful that it can lead to terrible acts of violence. In fact, some may argue with its definition as a horror movie since, nominally, the film mostly works as a crime procedural, tracking a police officer’s quest to find a man who somehow tricks otherwise innocent citizens into committing murder. But Kurosawa’s mastery of atmosphere is such that “Cure” is one of the most frightening cinematic experiences of all time; it causes an overwhelming atmosphere of terror not based on any monsters or supernatural elements, but simply on the implications of just how much darkness lurks beneath our shared construct of civilization.

14. The Changeling (1980)

More than perhaps any other horror subgenre, the haunted house picture lives or dies by the quality of its atmosphere, because for most of its runtime, the film can only suggest a malignant presence rather than actually show frightening creatures or skate by with jump scares – meaning, it can only be scary if the filmmaker manages to create a sense of dread.

And that’s just what director Peter Medak achieves in “The Changeling,” one of the greatest classics of the haunted house genre – though calling it that is to diminish the impressive tonal balancing act at work in this film, which goes from an introspective character study of a grieving father to an investigative mystery without breaking a sweat. This mishmash of genres works so well because of Medak’s amazing grasp of cinematic language; the way he uses slow, prolonged tracking shots alone would be enough to disturb the viewer. Thankfully, the film has much to offer elsewhere too, be it the gothic production design or the methodical editing (the slow burn pacing is a fundamental element of the overall tension).

Low in explicit frights but heavy in mood, “The Changeling” is proof that atmosphere is everything one needs to create a truly scary movie – and this film could be the reigning champion of the haunted house genre were it not for a certain picture from 1961.

13. The Innocents (1961)

Fifty years on, Jack Clayton’s seminal masterpiece continues to be the pinnacle of the haunted house subgenre, the one by which all others are measured – and the one from which many a copycat have been born.

What else can even be said about “The Innocents” at this point that hasn’t already been widely dissected by critics and scholars over the decades? Safe to say, if you’re a horror fan, or even simply a cinephile with no particular affection for the genre, you’ve seen this classic adaptation of Henry James’s ghost story – such is its mark on cinema. But just in case a reader is unfamiliar with the film’s brilliance, it’s no hyperbole to call it one of the most formally formidable (the deep focus CinemaScope cinematography is an absolute stunner), ambiguous, and layered genre movies ever made.

And that’s not even going into the reason for why the film landed onto this list: the sublime atmosphere. Wide angles, damp swamps, spectral apparitions just on the edge of the frame – it all comes together to create this sense of losing one’s mind in the presence of other-worldly mysteries. A masterpiece.

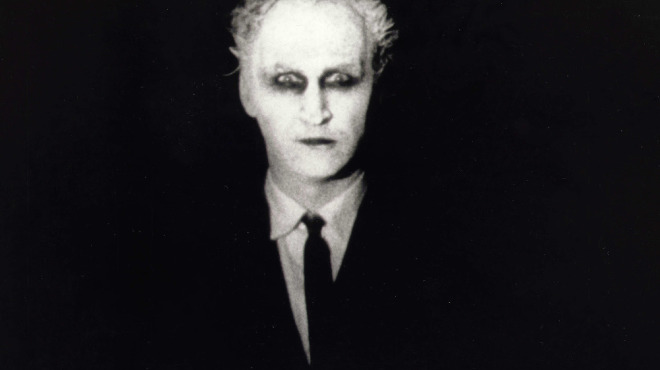

12. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

German expressionism is the birthplace of cinematic horror; the seeds for every aesthetic and stylistic element that was to define the genre were first planted during the silent era by masters such as Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau.

Though not as monolithic a name as those two, Robert Wiene made what is possibly the greatest movie of that whole movement, not only one of the best silent films there is, but also a horror nightmare worthy of any contemporary fright fest: “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.”

All of cinema is predicated on the strength of images to really affect the audience on a visceral, subconscious level: what truly separates good from great is that elusive ability to manipulate the elements of film language (composition, lighting, design, editing) and sharpen them into a delivery mechanism of pure feeling. And if that’s true of any genre, it’s particularly essential with horror, given that it’s very difficult to scare anyone with dialogue alone. So, all this to get to “Caligari” and this movie’s utter perfection with regards to that: the spectacular sets, the remarkable angles, the gobsmacking cross-cutting is visual storytelling at its purest; the apogee of gothic atmosphere in all of cinema.

“Nosferatu” is culturally the most remembered film of German expressionism, due, of course, to the greatness of the film, but also to elements outside of it, like the popularity of vampire stories and the myriad of remakes and derivatives that spawned from it. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” doesn’t have those elements going for it, but make no mistake: it’s the best thing to come out of that time and place.

11. Vampyr (1932)

Coming a few years too late to be officially considered a part of the German expressionism canon, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “Vampyr” is nevertheless every bit in keeping with the movement’s aesthetic principles; a sort of spiritual successor to the original pioneering classics.

It does have some notable differences from those films, mainly the fact that it’s actually spoken (and in multiple languages at that), but Dreyer, like his silent successors, is mostly interested in the power of abstract atmosphere, favoring mood over narrative. It might be a recipe for boredom in the hands of a lesser filmmaker, but Dreyer’s images are so sublime that it works in this film as pure visual poetry.

The canon of transcendental cinema (films that seek to portray that which is ineffable, that deal with spirituality through forme itself) is vast, and composed almost exclusively of stern art films, but “Vampyr” is not only transcendental, but very much a horror movie. Talk about atmosphere.

10. The Beyond (1981)

As said in the previous entry, sometimes if the atmosphere is strong enough, it can take precedence over story, flipping the more traditional narrative-oriented mode of filmmaking. In terms of horror, that’s never been truer than in Lucio Fulci’s manic, illogical but incredible “The Beyond.”

The movie’s “story” is borderline incomprehensible past the core concept (a woman inherits a hotel that harbors a passage to Hell), with scenes blending into each other seemingly without any sense of continuity or logical progression. But that’s also where the movie’s strength comes from, that oniric quality that defies our preconceptions of narrative and takes the audience into pure nightmare territory, each new bizarre set piece contributing to the overwhelming sense of dread; the sensation that you’re being led into a wholly dangerous new plane of existence.

“The Beyond” is surrealistic cinema at its finest; abstract, chaotic and deeply disturbing, proving that Fulci, despite having a (admittedly well-earned) reputation for being a king of schlock and gore, was an equally adept master of the oniric.

9. Carnival of Souls (1962)

And in the topic of surreal, dread-filled oniric rides into a dangerous underworld of death, “Carnival of Souls” might be the greatest example of that very, very specific horror subgenre.

It’s a testament to this film’s inexorable power that despite its micro-budget (the cheapness of the production has only been highlighted by time), it not only held on to its status as a classic, but it also has, if anything, grown in appreciation over the decades. That’s because, budget issues aside, Herk Harvey’s film is wildly ahead of its time in almost every way. The sensitive, astute depiction of mental illness is unequaled even to this day; the disorienting, paranoid atmosphere predates Roman Polanski’s whole style by a few years and, in general, the sheer force of will necessary to achieve artistic greatness under harsh economical constraints is a prelude to the entire American movement that would only come to full power some decades later.

As is almost always the fate of truly visionary works, “Carnival of Souls” languished in obscurity in its own age, unappreciated – but, thankfully, unlike in the film’s doomed protagonist, in this case time was an ally and today the movie stands tall as an essential classic of horror.