After a release botched by the pandemic that put it on hold for over a year, The French Dispatch has at last arrived at every theater worldwide. The film introduces us to a number of episodic stories recounted by an American journal staff located in a fictional French town. For better or worse, it’s the most Wes Anderson movie Wes Anderson has ever concocted—a distillation of all the themes, visuals and zany humor he’s been ironing out throughout his career.

Like any worthy director to ever pick up a camera, Anderson has drawn inspiration from a diverse set of films when crafting his own anthology period piece. Our primary source comes in the form of a list put together by the producers featuring those films that “provided inspiration to the cast and crew” during its conception, including five personally handpicked by the director himself. From Francophone staples to newsroom classics, we have compiled ten that should certainly scratch an itch after watching The French Dispatch. Without further ado, let’s go through each one of them.

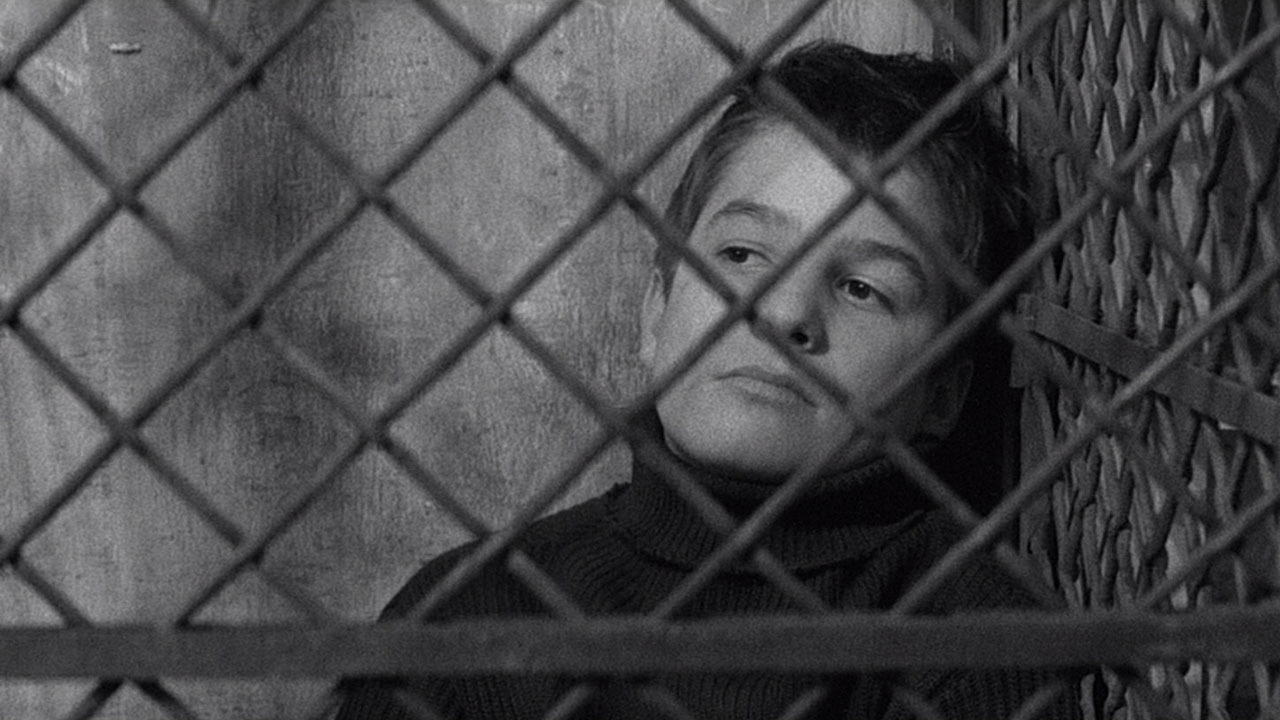

1. The 400 Blows (1959)

Kicking things off we turn to François Truffaut’s magnum opus, a staple in the French New Wave that’s still (rightfully) hailed as the golden standard when it comes to debut features.

The loosely autobiographical story puts us in the shoes of Antoine, a wayward Parisian boy who constantly gets himself into trouble, whether it’s by skiving off school or committing petty crimes. The driving force behind the film is its examination of authority, mostly through the lenses of neglecting parents and scornful teachers. Rather than receiving any form of valuable guidance, young Antoine is belittled, rejected and scolded by practically every authoritative figure in his life, which ultimately pushes him to pursue a life free of their shackles.

Wes Anderson has stated that this film in particular “was one of the reasons I started thinking I would like to try to make movies”. According to Robert Yeoman, Anderson’s longtime cinematographer, The 400 Blows also figured among the five films the director showed to the crew while shooting The French Dispatch. Granted, it may not share any of the light-hearted quirkiness or colorful palette that have become trademarks in his career, but the film’s poignant exploration of alienated youth rebelling against oblivious grown-ups is a theme ingrained in Anderson’s body of work.

2. His Girl Friday (1940)

Of all the innumerable gambits and devices that Wes Anderson deploys in every film, his idiosyncratic use of language may be the most defining. The French Dispatch doubled down on his penchant for snappy dialogue and wry deliveries with Anderson’s most tongue-twisting screenplay to date—one where the director seems on a race with himself to fit as many lines as humanly possible.

Any enthusiast of Anderson’s verbose parades and nauseating pace will feel right at home watching Howard Hawk’s exhilarating romcom. Similar to The French Dispatch, this film is a heartfelt ode to old-school journalism—albeit one saddled with an unshakable dose of cynicism that carries over in the whole story. Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell star as a hard-nosed editor and an investigative reporter who join forces to cover one last scoop together before calling it a day. Both Anderson and Hawks construct their narratives to fit around their overlapping dialogue—the former being at all times in service of the latter.

The sarcastic remarks, the witty comebacks and rapid-fire banter coming at breakneck speed—everything we’ve grown to expect with Wes Anderson can be found in this classic too.

3. Submarine (2010)

Wes Anderson has made a career out of illustrating the growing pains that come from an early age. From Rushmore to Moonrise Kingdom, his lengthy canon of lead characters shares a fair number of traits—young, neurotic, socially inept, conceited and borderline insufferable, but always infinitely relatable. What’s more, they all seem to deeply yearn for a stable role model to steer them in the right direction, which is often nowhere to be found in their dysfunctional nuclear families.

Oliver Tate, the eccentric 15-year-old teen anchoring this British film, checks off every box in the above description. In fact, it isn’t hard to imagine him hitting it off with Max Fischer or Thimothée Chalamet’s character in The French Dispatch. Oliver is used to hiding his inner turmoil in a facade of outward indifference, but struggles to do so when confronted with his parents’ imminent divorce or his first serious relationship with a fellow classmate.

As a coming-of-age film, Submarine treads eerily familiar ground to Wes’ oeuvre. In terms of visual cues and aesthetically-pleasing color palettes, the movie wears its inspiration on its sleeve as a very conscious product of Anderson’s school of filmmaking. It may not be as good as the real deal, but it does come awfully close.

4. Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

What seems to thread together all three segments in The French Dispatch is not so much the fact that they come under one banner—the Liberty Kansas Evening Sun—but the emotional state in which every character finds themselves in. Ennui-sur-Blasé, the cleverly fitting name to the fictional French town where the whole story takes place, gives us an accurate diagnosis of what’s clouding above everyone’s head. For all their lively occurrences, no one seems capable of escaping their own spiritual disillusionment.

Jean-Luc Godard—often hailed as the godfather of the French New Wave—wrestled at length with his own existential concerns throughout his long, illustrious career. Arguably the most iconoclastic of his peers, he never shied away from tackling contemporary problems or mirroring the cultural malaise of his time. Both the awkward romance and youth activism seen in the monochrome ‘Revisions to a Manifesto’ segment of TFD certainly owes a debt to Godard’s Masculin Feminin and La Chinoise. Dissatisfaction once again takes center stage in another of his heavy hitters, Vivre Sa Vie, a scathing portrait of Paris’ dark underbelly seen through the lens of an actress-turned-prostitute (brought to life by an impossibly enchanting Anna Karina).

5. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

Depending on the viewer, The French Dispatch is a film that will either fill you with joyful jubilation or bittersweet melancholy. Your mileage may vary, but Jacques Demy’s classic musical can prove to be a similarly paradoxical experience. As an exercise on visual grandeur, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg hits all the right notes—up to the last detail of its closing frame is carefully rendered and brought to life to glorious results. The story itself, a poignant romance concerning a lively clerk and an auto repairman sent to combat in Algiers, is engaging but nothing more than a formal prerequisite for indulging our senses with an overwhelming display of music and color.

If one considers Wes Anderson as a visual storyteller above all things, then The French Dispatch poses as his most ambitious endeavor yet. Every attribute that has become synonymous with his style—the gaudy production design, colorful mise-en-scène or symmetrical compositions—is magnified and reinforced almost to a fault. It’s precisely in that respect where Anderson’s extravagant anthology echoes Cherbourg the most: as two masterfully crafted movies that struggle to overcome their own self-indulgence.