When it comes to thrillers deliberately crafted to make your skin crawl and haunt you long after the credits roll, Park Chan-wook is second to none. With iconic masterpieces such as ‘Oldboy’, ‘Thirst’ or ‘Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance’ under his belt, it wouldn’t be too much of an overstatement to claim that he’s pushed the envelope of the genre as much as any given filmmaker in the past few decades.

The Korean auteur is once again on everyone’s lips after picking up his first Best Director nod in Cannes for ‘Decision to Leave’, a new romantic thriller that has premiered with much fanfare at the Croisette. This marks a welcomed return to form for the master of poetic mayhem after a six-year hiatus since rendering us speechless with ‘The Handmaiden’ back in 2016. And though being recognized at the biggest stage has been long overdue to a trendsetting figurehead in world cinema, Park Chan-wook is merely reaping the benefits of over two decades of filmmaking of the highest order.

Long before ‘Parasite’ sent shockwaves all around the industry with a historic awards sweep, Park helped put South Korean cinema on the map with a string of stylized thrillers that took the world by storm and instantly established him as a force to be reckoned with. Subsequent efforts have only reinforced his global stature as one of the most transgressive voices in the industry, amassing a fervid following overseas as well as in critic circles for his morbid portraits of the human condition, the folly of revenge and the inescapable stranglehold of fate.

But before putting his stamp on contemporary cinema, Park Chan-wook was once a philosophy student and bidding film critic. Across that time, he passed judgment on many of his peers including some of the most celebrated directors of all time. And he did so without ever biting his tongue or sugar-coating his opinion, no matter how controversial — tearing apart renowned classics like ‘Citizen Kane’, ’Full Metal Jacket’, ‘Chungking Express’ or ‘Psycho’ without a hint of hesitation. But he wasn’t shy when it came to singing the praises of plenty of films that influenced his own work either. Drawing from a plethora of interviews, lists and reviews, we have assembled ten that’ve been blessed with his seal of approval and that should come in handy as we celebrate his latest nail-biter.

1. Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Few filmmakers know how to tell a story and send shivers down our spines better than Alfred Hitchcock. In fact, it’s hard to find a thriller in the past half century that doesn’t owe something to the master of suspense. Not without reason, Park films have triggered many comparisons with Hitchcock, with many critics going as far as anointing him as his spiritual successor. Any parallels between both are taken as a compliment for the Korean director, who cited him as one of the biggest reasons he decided to pursue his directorial aspirations in the first place.

“One day, I saw ‘Vertigo.’ During the movie, I found myself screaming in my head, ‘If I don’t at least try to become a film director, I will seriously regret it when I’m lying on my deathbed!”, the director revealed during an interview for the New York Times. “After that, akin to James Stewart when he was blindly chasing after some mysterious woman, I searched aimlessly for some kind of irrational beauty.” Park highlighted the scene where “the real character that Kim Novak plays, Judy, fully becomes the character of Madeline, and her transformation from one to the other is complete” as one of his favorites of all time.

2. M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

Revenge is a recurring motif burrowed deep into Park’s body of work. Far from endorsing violent retribution, his films work best as incisive morality plays that urge the audience to reconsider their primal instincts and dwell on the futility of such endeavors. One of the darkest sequences the director has ever churned out can be found in the climax of ‘Sympathy for Lady Vengeance’, where a group of grieving parents viciously get back at the serial kidnapper who abducted and murdered their children.

This particular scene is cribbed straight from Fritz Lang’s seminal thriller, which probes similar themes of institutional retribution and mob justice during an eerily reminiscent conclusion. Vengeance is once more the driving force behind the story, which centers around another child killer who triggers a city-wide manhunt across the streets of Berlin. After the police investigation hits a snag, the local crime syndicate takes matters into their own hands — hunting down the culprit and sentencing him to death in an underground court in front of all the victims’ parents. As the screen fades to black, a grief-stricken mother laments that “no sentence will bring the dead children back” — a simple statement that underscores what Park Chan-wook has been desperately trying to convey for the better part of the century.

3. The Housemaid (Kim Ki-young, 1960)

Though Park Chan-wook might not be associated with themes of economic struggle and class resentment to the extent of Bong Joon-ho or Lee Chang-dong, a closer look at his films shows he’s just as much a moralist as his peers. From ‘Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance’ and ‘The Handmaiden’ to ‘Stoker’, his characters range from social outcasts, oppressed women and marginalized workers all fueled by rage and guilt.

This staple in Korean cinema uses many of the aforementioned themes as the baseline for its exploration of social and gender inequalities, thrusting us into an upper-class household where all hell breaks loose after a scheming, two-timing housemaid is hired. Connecting the dots between the groundwork for this anti-bourgeois tale and ‘The Handmaiden’ is fairly easy to anyone who’s seen Park Chan-wook’s period piece.

Though he rarely rewatches films, Park claims he always feels the urge of revisiting this classic courtesy of Kim Ki-young — a director he regards as the greatest in the history of Korean cinema. “He’s able to find and portray beauty in destruction, humor in violence and terror. I’m still making films that are too modest compared to his, but I will continue to work hard to make films as daring and brave as his.” That’s high praise coming from one of the most provocative filmmakers of our time.

4. Ms. 45 (Abel Ferrara, 1981)

When prompted to name his favorite revenge movie — not including his own Vengeance trilogy — Park Chan-wook mentioned Abel Ferrara’s grindhouse classic “for Zoe Tamerlis’ beauty”, claiming he was at a loss of words upon first viewing. In hindsight, it doesn’t come as a shocker to learn this was right up his street considering his artistic obsessions as a director. Much like Park’s work, ‘Ms. 45’ is not for the faint of heart and conceals plenty of moments that can lodge in one’s memory banks — blending exploitation sleaze and arthouse trappings in an explosive cocktail of stylized bloodshed.

The predator become the prey after a deaf mute decides to even the score and go on a killing spree after being raped by wandering around the streets of New York City and blasting any man that picks her up with her .45 caliber handgun. Watching our female vigilante claw her way back to retribution can be as morbidly cathartic as watching any of Park’s heroines lay waste on their abusers, but the fact that we find it an unabashedly exhilarating affair says quite a lot about our own emotional desensitization to on-screen violence.

5. High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

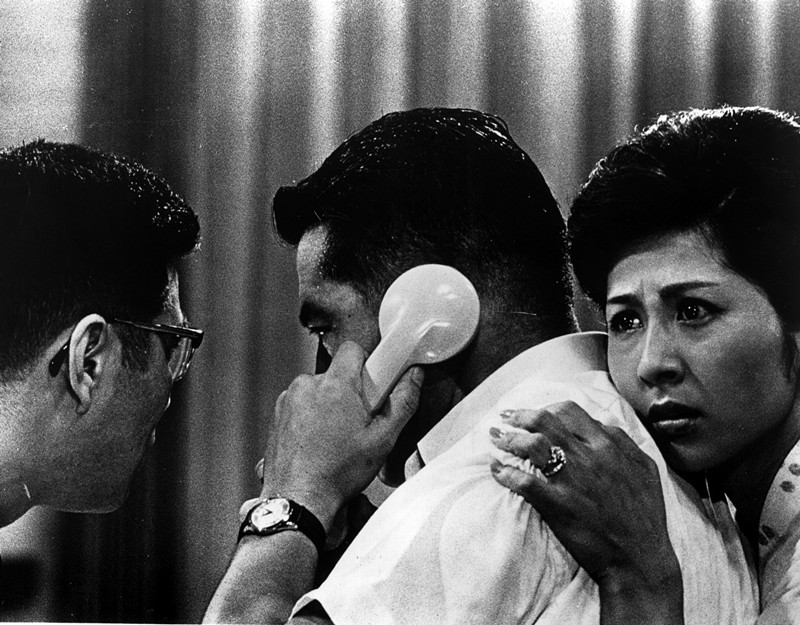

Kidnapping takes center stage in several of Park’s films, most notably in ‘Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance’, where a deaf-mute abducts the small child of his former boss — a greedy businessman who recently fired him — in order to raise money for her dying sister’s kidney transplant.

When coming up with his own morally ambiguous crime tale, the Korean director sought inspiration in Akira Kurosawa’s classic, one he listed among his ten favorite Asian movies of all time. ‘High and Low’ shares a similar thematic fabric to ‘Mr. Vengeance’, disguising itself as a conventional thriller first before showing its true colors as a scathing portrait of class relations. The plot is set in motion when a wealthy shoe executive becomes the victim of extortion when his chauffeur’s son is abducted and held for ransom, creating quite a dilemma for all parties involved.

“I thought it would be good to see the movie first. Then I gave up. I thought, ‘No one can make kidnapping movies anymore’. I wanted to somehow chew his movie and digest it and make my own with the nutrients. But even if I couldn’t make a movie that surpassed him, I could at least try to make a movie that felt different from him.”