12. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013)

Isao Takahata’s final film as director is another radical departure from Ghibli’s usual animation style. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is done in a unique style inspired by Japanese watercolor painting, and based on the ancient Japanese Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. It is a fantastical story about a farmer who comes across a tiny girl inside a bamboo shoot, and takes her home and raises her as his own, convinced that she is royalty. We follow this girl as she grows up and is taken into the nobility, and watch as her need for independence grows as she is trained to become a princess.

At 2 hours and 17 minutes, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya clocks in as one of the longest animated films ever made. While it is a very fine film, perhaps some of this runtime could have been trimmed, particularly from the extended subplot involving various suitors going on quests to win Kaguya’s hand. It is lengthy and slow-moving, but rewarding, containing flashes of brilliance such as a scene where Kaguya is upset and the animation itself grows rougher and messier to match her mood. While the film is certainly a work of art, it is more admired from a distance than watched nowadays, lacking the enthusiastic following that many Ghibli films have.

11. My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

Totoro has become the mascot of Studio Ghibli and one of its most iconic characters. But despite how famous and highly praised the film is, it’s actually better to go into it without any lofty expectations. My Neighbor Totoro is a simple, small-scale story about a family moving into a new home in the countryside and meeting some mysterious forest spirits that live there. And there really isn’t much else to it: like with many Ghibli films, the magic is in its simplicity. It’s a calming, positive, low-key kind of film, and it’s best to go in with that expectation rather than hoping for some grand adventure.

Totoro is a delightful and cuddly creature, the family’s interactions are adorable to watch, and some of the images border on surreal, such as the famous Cat-Bus. Some dark fan theories have been concocted about this film, but in all likelihood the film has such an aura of innocence and childlike wonder, people assume some sinister message must be lurking under the surface. In this case, what you see is what you get.

10. Pom Poko (1994)

Pom Poko is somewhat infamous in the West for a scene that involves what the English dub modestly translates as “raccoon pouches”. The film is about a group of tanuki, or Japanese raccoon dogs, which have been prominently featured in Japanese folklore as shapeshifting tricksters. Part of the lore behind the tanuki is that they have prominent testicles which they can magically increase to massive size, and the film openly portrays this. This concept, which seems so strange to those outside Japan, may have dampened its international reputation. Which is a shame, because this is a wildly entertaining, funny film with a good message.

Many of Studio Ghibli’s films have an undertone of environmentalism. But few argue for the protection of nature as passionately and explicitly as Pom Poko. The film’s plot involves the tanuki fighting against a giant suburban development project which is destroying their land. The tanuki are made up of some fun and memorable characters, and their antics are a joy to watch. It all culminates in a surprisingly somber ending: as in life, the struggle of humanity against nature is very one-sided. The environmental messaging in this film isn’t exactly subtle, but it is a worthy message to pass down to the next generation.

9. Ponyo (2008)

Ponyo is very loosely based on The Little Mermaid, but it departs from the original fairy tale in so many different ways that to reference it is almost counterproductive. In this story, Ponyo is not a mermaid in the traditional sense but an adorable little blob who has a taste for ham, and gets adopted by a five-year-old boy, Sōsuke. It isn’t quite a romance, but it is an incredibly charming, and cute, family film.

The film is filled with gorgeous imagery and a surprising amount of emotional nuance. Sōsuke’s mother, raising him alone while his father is away at sea, is an interesting and dynamic character. Ponyo herself is childish but immensely likable. And the villain, Fujimoto, as is so often the case in Ghibli films, is not simply a mindless evildoer. It would be difficult for any viewer, young or old, not to succumb to this film’s charm.

8. The Wind Rises (2013)

Declared by Miyazaki to be his final film (until the announcement of the upcoming How Do You Live), The Wind Rises definitely has the feeling of a swan song. It is a fictionalized story of the life of Jiro Horikoshi, an airplane designer for Japan during the Second World War. Jiro is fascinated by aircraft – “beautiful dreams”, he calls them. It is easy to see why Hayao, a fellow airplane enthusiast, chose to tell his story.

The film is filled with haunting and striking images: countless otherworldly planes soaring in Jiro’s dreams, a devastating portrayal of the 1923 earthquake and the horrific aftermath that followed. It portrays Jiro’s moral qualms about creating machines that are being used to take innocent lives. How responsible is this man, whose only desire was to create innovative and beautiful technology, for all the killing that his machines were used for? It is an interesting question, and while the film addresses it, its main focus remains on the personal life and imagination of the man. And that is the film’s strong point: the protagonist’s desire to create something beautiful, and the way he and others undergo endless hard work to make it a reality. After a lifetime of creating films to cater to other groups, The Wind Rises is Miyazaki’s most personal work.

7. Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Technically speaking, this film was made before Studio Ghibli was officially titled as such in 1985. However, this and one other film were directed by Hayao Miyazaki, using the team that would go on to become Studio Ghibli, and made very much in Ghibli’s style and ethos. Based on the Lupin III anime series previously worked on by Miyazaki and Takahata, no knowledge of the franchise is necessary to sit down and enjoy The Castle of Cagliostro, the proto-Ghibli film.

Technically it is an action film, much-inspired by old adventure serials, but already elements of Ghibli’s fantastical tone are present in the environments and the fluid, vibrant animation. Lupin himself is a lovable rogue rather than the antihero he was in the original series. It is interesting to see tropes that Miyazaki would abandon as his creative vision evolved, such as damsels in distress, dastardly villains, thrilling action and car chases. But these elements are portrayed about as perfectly as can be, and the film’s energy and enthusiasm is infectious.

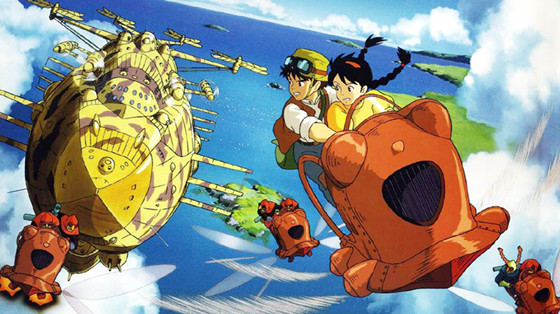

6. Castle in the Sky (1986)

The first film to be officially produced under the Studio Ghibli name, Castle in the Sky embodies everything magical about the company’s vision. It is a perfect blend of fantasy, steampunk, and high adventure. Following the adventures of a boy and girl, Pazu and Sheeta, in their search for the legendary floating city of Laputa. They come across air pirates (led by a tough and hilarious older female pirate voiced in English by Cloris Leachman), strange flying machines, ancient robotic technology, and other wonders.

Unlike Miyazaki’s later work, this film possesses an unambiguous villain, a devious government agent dubbed by Mark Hamill, who of course hams up the evilness. The world and characters are timeless and a joy to experience, particularly the pirates, and the animation, of course, doesn’t disappoint. Among the most striking images in the film is a giant robot covered with moss and vegetation. In a way, that image summarizes Miyazaki’s work: a love for machinery and the inner workings of technology, married with a great reverence for the natural world.

5. Princess Mononoke (1997)

Princess Mononoke is a film that strikes us as so effortlessly original, so completely unique, that one wonders why there aren’t more films like it. It is one of Studio Ghibli’s most monumental efforts, a fantasy epic involving gods, demons, spirits, and a grand quest. Not only that, but its wide English-dub release in the USA was many Americans’ first introduction to Studio Ghibli. It is a perfect response to those who believe that animation is only for children, or cannot be a serious art form.

The film explores the conflict of man versus nature, and does so in a surprisingly nuanced and balanced way. In the film’s world, humans are in conflict with spirits and animals, but neither group is portrayed as necessarily evil. Both groups are simply trying to survive: humans by expanding industry and civilization, animals by fighting against this intrusion on their natural resources. Lady Eboshi, a prominent leader in the film, is an especially complex character: she is presented as a kind woman who takes in and cares for the sick, but wishes to kill the Great Forest Spirit, the most powerful spirit in all nature, because she views its existence as a threat to her people. San, the girl raised by wolves who has become something of a symbol for the film, is surprisingly underdeveloped in comparison. But that doesn’t ruin the majesty and artistry of Princess Mononoke.

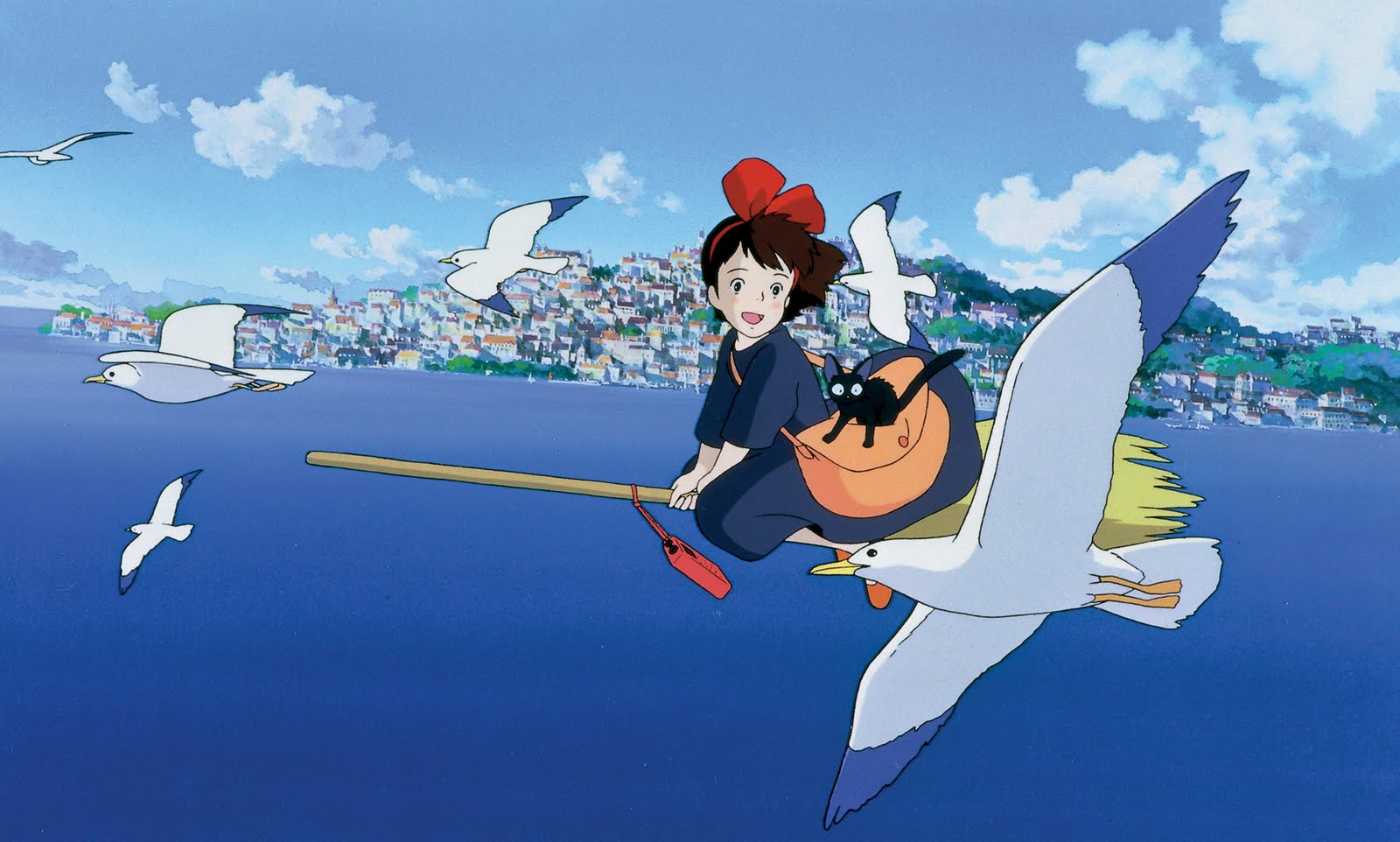

4. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

Kiki’s Delivery Service is a deceptively simple film. Not too much happens in it. On its surface, it is about a young girl going through education to become a witch. In reality, not too many “witchy” things occur in the film: Kiki has a talking cat and flies around on a broomstick, but that’s about it. It is simply a very psychologically insightful portrait of a 13-year-old girl going through the trials and hardships of growing up.

One might be tempted to say there is no major conflict in the film: no villain or catastrophe or underplot that builds into a climax. But the conflict in Kiki’s Delivery Service is internal: Kiki’s struggles over whether she can believe in herself, her fears and anxieties over what direction she wants to go in life, her slide into moodiness and depression. It’s all a perfect capsule of how it feels to grow out of childhood. And Kiki’s gradual loss of her powers, while temporary, is relatable for anyone who has ever tried to hone a skill and met with failure after failure. Kiki’s Delivery Service tells us that we have to persist, and press on.

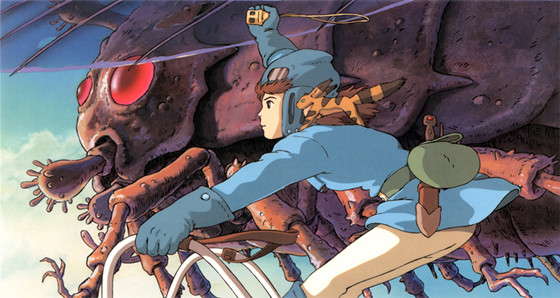

3. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Nausicaä, while not as widely praised as Princess Mononoke, is another epic with an even more original setting: a post-apocalyptic version of Earth that has been reduced to vast deserts and toxic jungles populated by giant insects. This is another film technically created before Studio Ghibli was, but is widely considered a part of its library, and to this day it is one of their most striking and impressive films.

Nausicaä features a complex world with a variety of different factions, with different technologies and ways of life, battling it out. Not all the details of the world are revealed to us, but the economy of the storytelling is remarkable, and those who are interested in learning more can always check out the manga it was based on, created by Miyazaki himself. Nausicaä herself is among the studio’s greatest heroines, a teenager who is trying to make peace between the different factions and become a leader of her people, while at the same time expressing human vulnerability. It all builds up to a gigantic climax with some of the studio’s most beautiful imagery. It takes place in a world that looks and feels alien, but at its heart is a boldly original, and human, story.

2. Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Grave of the Fireflies is notorious for being a depressing tear-jerker of a film. But this is not on account of any cheap sentimentalism: the film is a sophisticated and unflinchingly realistic portrait of the experience of two Japanese children during the Second World War. The older brother, Seita, and the older sister, Setsuko, are saddled with their aunt after the death of their mother and the conscription of their father into the military. But infuriated with his aunt’s nagging and domineering attitude, Seita decides to go out and live on his own on the outskirts of town, taking his little sister with him. This would turn into disaster and tragedy, as the film tells us minutes into its runtime.

It becomes clear that Seita cannot survive on his own and provide for his younger sister, but his pride and need for independence forbids him from seeing the truth. The animation is, fittingly, not trying to look beautiful so much as trying to give an accurate portrayal of reality. It is a searing indictment of war, but also a portrayal of a personal tragedy that could happen in any time or place, during any time of crisis. It is a work of stunning maturity so early in Studio Ghibli’s lifespan, Isao Takahata’s masterpiece. It is living proof that animation can be a serious art medium for adult viewers, and a great yet devastating film in its own right. While Ghibli would never return to quite the same level of darkness and adult themes, Grave of the Fireflies might have said all that it is necessary to say on its unspeakable subject matter.

1. Spirited Away (2001)

Since it first premiered, Spirited Away has garnered the highest praise from critics and audiences alike. What makes it Studio Ghibli’s masterpiece? The film is simply a feast for all the senses: the visuals are the greatest the studio has ever created, the music is melancholically beautiful, the story is so engaging and archetypal that it feels like an age-old fairy tale – but it is simply the product of one man’s imagination and an animation department’s hard work.

What truly cements the film’s greatness is its keen sense of atmosphere. Fans of Tarkovsky and Ozu know of cinema’s power to draw the viewer in, to slow down the action and take the time for the viewer to properly soak in a scene. Not many modern Hollywood movies dare do this, but Miyazaki confidently taps into this technique, creating liminal spaces of meditation and quiet that only increase in power the more one sees them. Scenes of epic scale and visual grandeur, too, approach the limits of what cinema is capable of. Every corner of the screen is packed with detail in the film’s strange, dreamlike world, and there are countless little moments of animated realism that invite the audience in to be a part of it.

We discover this world through the eyes of Chihiro, a young girl. Her journey into the Spirit World is a tale as old as civilization itself: a descent into and return from the underworld, a threatening subconscious world of shadows and phantasms. A viewer would profit from a knowledge of Japanese mythology going in, but anyone from any culture can understand the images explored by the film: the gluttonous parents’ transformation into pigs, the terrible old hag Yubaba, and that embodiment of human loneliness and longing, No-Face. The film has an almost mystical pull that is easier to experience than it is to explain. There are moments where the storytelling seems rushed or strange to us, such as the sudden reveal of Haku’s backstory or Chihiro’s unexplained identification of her parents at the end. But there are oddities like these in countless great works of literature, not to mention cinema. These unexplained bits in Spirited Away do not disturb us, because they do not interfere with the beauty and sublimity of what it has accomplished. It is not only Studio Ghibli’s greatest film, but a cinematic masterpiece.