4. Terrorizers (1986)

Terrorizers feels Yang’s most fatalistic depiction of urban malaise. Usually, he counterbalances his dreadful existentialism with a healthy dose of faith in humanity to sort things out. That is not the case with Terrorizers, where he paints a much bleaker world, one with deception, adultery and murder all running rampant.

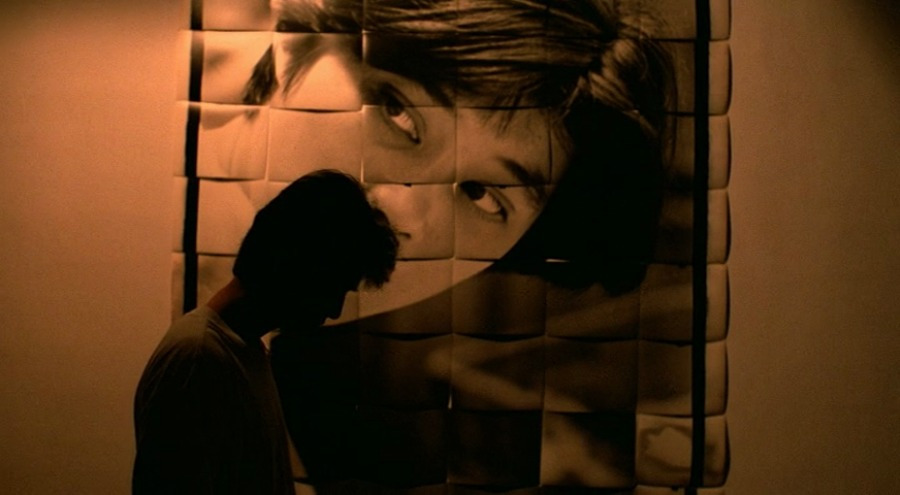

In this film, characters face the uncertainties of the future not only with worry but with outright anxiety. And while movies like Yi Yi or That Day on the Beach weave together their interlacing threads through love or kinship, every moving piece in this film feels independent, with random strangers colliding by pure chance. It is probably Yang’s most cryptic story, offering four central narratives. The first puts us in the middle of a dysfunctional marriage between a neglectful career-man and an artistic writer who is struggling to finish her novel. At the same time, we follow a voyeuristic photographer who becomes infatuated with an enigmatic female criminal he captured with his camera during a shoot-out in an alleyway.

Living in a world driven by unpredictability fills these characters with despair and an irreparable alienation with their surroundings. One of the recurrent themes is how desperately they cling on to fiction and fantasy to cope with reality. The female writer finds a way to rationalize her miscarriage and monotonous relationship by pouring her angst into her novels, while the young photographer evades his conscription draft letter by isolating himself in a room full of his camera snapshots. The real terror is the world around them, and every character wraps themselves in their own private one safe from the chaotic nature of life.

3. Taipei Story (1985)

One constant trait of Yang’s filmmaking is the use of space to convey broader social realities, with this one being the quintessential example. Taipei Story focuses on a dysfunctional couple living in Taipei. Chin is an aspiring architect while her husband, Lun (portrayed by Hou Hsiao-Hsien), still reminisces about his glory days as a promising baseball player. Their broken relationship is at a crossroads, one constantly looking ahead in the future while the other is forever stuck in the past, as disconnected from each other as they are from their surroundings.

The concrete jungle of Taipei takes front stage, almost becoming a character of its own, and symbolizing the identity crisis and desperation of modern Taiwan. Neon-lit high-rises and empty spaces are consistently mirrored and reflected through windows and glasses. The urban landscape feels inescapable, one that menacingly towers above everyone in it.

There is a generational ridge between those still living by the old values that favor family and tradition like Lun, and those fully embracing the new Western ideals that encourage individualism and economic freedom like Chin. They both are in a constant struggle to find meaning and value in their busy but empty lifestyles and as a result, they entertain the idea of starting over in America. They cling to a fleeting hope that they will find a better life abroad, one that frees them of any of the problems that haunts them at home. But in a sense, America is just an idealized gateway, the ultimate solve-all panacea, and nothing more than that.

2. A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

The fact that either of the following two movies doesn’t sit at the very top of this list feels like a complete sacrilege, but if anything, it is a testament to Edward Yang’s incredible talent. For any other director, each one would easily be considered as the summit of their careers and their unquestioned masterpiece. But given how stacked his career was, it leaves us with a true embarrassment of riches where arguably the most important film of the nineties sits at number two in this list.

Already with three films under his belt, Yang culminated all of the themes and visual confidence he’d developed with this epic. If Taipei Story felt like his coming-out party, A Brighter Summer Day officially established him as one of the greatest voices in contemporary cinema.

Clocking in at almost 4 hours, the film weaves through early 1960’s Taiwan by putting us in the shoes of a group of teenagers who are experiencing love, betrayal and violence for the first time. Even in Yang terms, it feels novelistic, a sprawling narrative that brings alive a place and time with every little thread and character perfectly realized. The title of the movie is taken from Elvis Presley’s waltz-ballad “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”. Teenagers soak in pop culture, dancing to the tunes of 50’s rock and roll and flocking to John Wayne’s westerns. As the first generation to grow up in postwar Taiwan, they fill their voided identity with Western idols.

From street gangs to tragic romances, Yang paints a directionless youth that is a product of their oppressive environment. A Brighter Summer Day is a film about change, past and present, politics, growth and love, and one that far surpasses the sum of its parts.

1. Yi Yi (2000)

Yi Yi is Edward Yang’s swan song, and it’s safe to say the master left the best for last. It’s hard to put into words how transcendent of a movie this is. In a nutshell, it’s yet another bittersweet family drama set in Taipei, with a deck of characters stuck in different stages of life. But it would be totally shortsighted to sell it as simply that, the same way Citizen Kane isn’t just a newspaper drama or Paris Texas another romance flick.

Yi Yi is a celebration of life, a 3-hour long canvas that contemplates it in all its scope and length while begging for some self-reflection. The movie is bookended by a wedding and a funeral. Birth and death are two sides of the same coin, and we experience the whole spectrum of life, from childhood, adolescence up to adulthood and old age, through the overlapping narratives of three characters ruminating on their existence.

First we follow NJ, the patriarch of the family, a man full of regret and overwhelmed by the demands of adulthood. As he reminisces of one long gone love, we witness her teenage daughter experiencing hers for the first time, with all the uncomfortable growing pains that come with her age. Lastly, we have Yang-Yang, NJ’s ten-year old son, who embodies our inner curiosity and need for exploration.

In all his naive innocence, Yang-Yang starts taking pictures of people’s backsides with his camera so that they can see what they can’t for themselves. And his adorable endeavor perfectly captures the whole purpose of cinema. A gateway to endless human experiences that reshape our perception with small doses of truth. And Yi Yi is a film filled to the brim with them. It’s easy to get lost in the daunting prospects of life, so it’s comforting to have stories like this one to remind us why we’re here in the first place.