It is surprisingly difficult to find examples of science-fiction films which you could call optimistic. There are several reasons for this. One is that it is harder to tell stories about futuristic worlds in which everybody is happy. It also tends to be a symptom of how the popular imagination reflects the world shaping it. The current abundance of dystopian or post-apocalyptic films and shows is likely due to viewers finding the possibility of worlds even bleaker than ours to be more comforting than imagining a brighter one.

The popular culture benchmark for optimistic visions of the future is probably still Star Trek, a franchise which ran parallel with the present on the big and small screens for more than thirty years, but now consists mostly of prequels, suggesting that, at some point recently, it stopped being a story of the future and became a fantasy from the past.

There are other factors determining how uplifting science-fiction can be. The cyberpunk aesthetic of Blade Runner (1982) has practically become shorthand for a dystopian city of the future, and yet the film makes this world brutally beautiful and inspiring. Similarly, in Terry Gilliam’s retro-futurist Brazil (1985), which examined the present through the prism of a baleful future imagined in the past (by George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four), the dystopia is a technocratic fantasy world that the viewer would love to explore, if not for too long.

In contrast, the hopefulness of a particular sci-fi film’s outlook is no guarantee that it will not leave a sour taste in the mouth. Jindrich Polák’s Ikarie XB1 (1963) paints an ultimately triumphal portrait of interstellar travel, but its most powerful images are of desolation and terror. Doris Wishman’s kitsch classic Nude on the Moon (1961) is arguably one of the most optimistic films ever made about first contact with aliens, but its exploitation griminess makes it so depressing that this is practically nullified.

Here are ten works of science-fiction that celebrate a hopeful outlook, most of them now several decades old. Given that the future will probably look very different to what was widely imagined half a century ago, it is likely these will only continue to grow in popularity as objects of nostalgia.

1. Just Imagine (1930)

Like so much of Pre-Code Hollywood cinema, Just Imagine (1930) has to be seen to be believed. This one is a good example of how utopian ideas often age faster than dystopian ones, creating a future-world that would sound conventionally bleak were it not a lighthearted musical comedy.

In New York of 1980, where marriages are approved by the state, Aviator J-21 (John Garrick) is in love with LN-18 (Maureen O’Sullivan), but she will be forced to wed wealthy stuff-shirt Z-4 (Hobart Bosworth) unless J-21 can distinguish himself in some other way. The opportunity arises when he is offered the chance to lead Earth’s first mission to Mars. In the meantime, there’s a Rip Van Winkle subplot in which J-21 becomes custodian of Single O (El Brendel), a man from 1930 who ends up stowing away aboard the spaceship.

Just Imagine is impressive in its opening scenes, with a Hugh Ferriss-style futurist cityscape, traversed by propellor-driven aircraft, giving an idea of what a screen adaptation of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) produced in the 30s might have looked like. Beyond this the film shows its age, both as an early talkie and a Depression-era satire, particularly in drawing a dubious comparison between Prohibition laws and the state-control of women’s bodies. Despite this, Single O’s refrain “I dunno boys, give me the good ‘ol days!” would probably have sounded more encouraging than retrogressive at the time, and the film is enjoyable at least for the first half. The budget seems to run out once they leave Earth, like a bad episode of classic Doctor Who.

2. They Came to a City (1944)

In the mid-1940s, Britain’s Ealing Studios produced a number of wartime fantasy films in which displaced groups of people are thrown together in improbable situations. They Came to a City (1944) is the only one of these that could be classed as science-fiction. Directed by Basil Dearden, the story is framed as a thought experiment, with screenwriter J.B. Priestly, playing himself, transporting nine people from different walks of life to a nameless, ‘ideal’ city. Some of them choose to stay. The rest, for different reasons, walk away.

Like many British films of the era, this one pushes the war into the background, proposing that the greatest impediment to postwar utopianism will not be ideologies but the prejudices of ordinary people. Its cross-section of society does not look very diverse now (one third of the group are aristocrats), and the clipped accents risk making its heavy-handed message sound even more grating, but the characters mostly avoid coming across as caricatured, partly since it is optimistic enough to suggest not all of them are set in their ways.

The film was based on a play, which would explain why the city is never shown. The most we see is a svelte, modernist waiting area, but this is enough to touch upon the sense of visionary boldness it is striving for, though much of the work is done by Googie Withers as a breezy London bartender who tries to make us see the future as she envisions it, simply using her eyes. The film at least seems aware of its own didacticism, even ending with Priestly saying “thanks for listening” to the audience.

3. Forbidden Planet (1956)

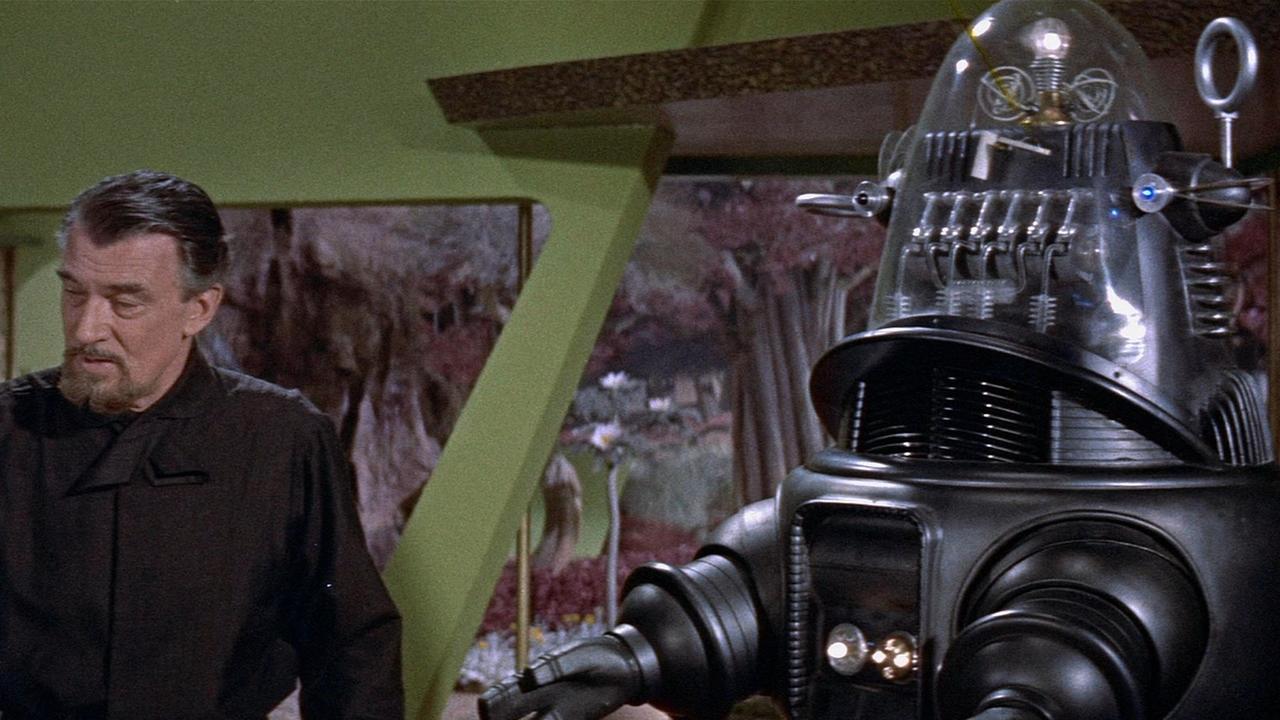

A military space crew, led by Commander Adams (Leslie Nielsen), arrives on the distant world of Altair IV to search for survivors of an earlier landing party. They soon learn the only inhabitants are scientist Morbius (Walter Pidgeon), his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis), and Robby the Robot. Things get complicated when the crew ignores Morbius’ warnings to leave the planet, and his daughter, alone, soon finding themselves attacked by an invisible creature.

Directed by Fred M. Wilcox, Forbidden Planet (1956) is perhaps the sci-fi film that best encapsulates the postwar futurist style, becoming a key influence on Lost in Space (1965-68) and Star Trek (1966-69). Its title and poster art made it out to be a fashionable monster movie, whilst its mention in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), and the jukebox musical sequel Return to the Forbidden Planet, helped turn it into a camp classic, but it remains a gorgeous and cerebral attempt at what would soon be called hard sci-fi.

Although much of the plot was derived from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, it ends up much closer to a Jules Verne story. The optimism of its fabulous designs is tempered by the final, cautionary message against hubris (and nuclear war), using the era’s obsession with psychoanalysis to suggest that the human intellect could never be trusted with technology powerful enough to create or destroy worlds. However, the narrator’s opening line declares that men and women were walking on the moon “By the end of the twenty-first century,” meaning that it is still, so far, ahead of the curve.

4. Road to the Stars (1957)

“First, inevitably, the idea, the fantasy, the fairytale, then scientific calculation. Ultimately, fulfilment.”

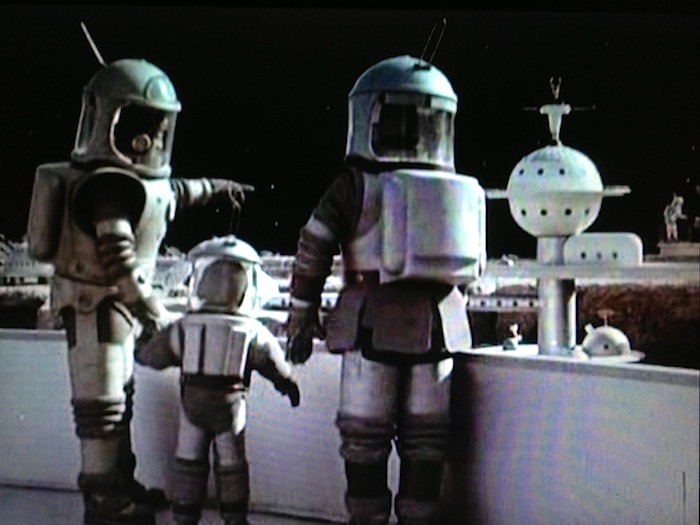

Released in 1957, Road to the Stars is a short Soviet docudrama on the emergent technologies of spaceflight, directed by Pavel Klushantsev. Beginning with pastoral village scenes reconstructing the life of pioneering rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (Giorgy Solovyov), it then leaps forward to the future, forecasting manned space orbits, people living on space stations, travelling to the moon, and ultimately living on it.

The film is an interesting artefact, without the clamorous propagandism that typified many films of its kind during the Space Race, featuring cheerful animations illustrating rocket propulsion, futurist rocket designs, and special effects that, while mostly quaint-looking, include impressive approximations of zero gravity. It also makes life in orbit look far more appealing than George Pal’s claustrophobic Conquest of Space (1955), showing a space station filled with books and cats.

5. Thunderbirds Are Go (1966)

The 1960s was an era of untrammelled optimism, and puppet series Thunderbirds (1965-66), perhaps more so even than Star Trek, may be the television premise that captured this perfectly. Practically every episode involved big, extraordinary machines going wrong, requiring even more extraordinary machines to solve the problem, and equilibrium is always restored without the technophilic arrangement of this future world ever being brought into question. This simple scenario was carried over to its first big-screen adaptation, Thunderbirds Are Go (1966).

Fittingly, the plot is a string of episodes: a spaceship bound for Mars takes off, crashes, then takes off again two years later, then someone has a nightmare about Cliff Richard, then six weeks later the ship lands on Mars and finds some martian snakes, and then, after another few weeks, it crashes again (it is nice to wonder if these martians are what the Mysterons of Captain Scarlet actually looked like).

This one is more of a guilty pleasure, particularly as it is perhaps the most ill-considered widescreen film ever made, consisting largely of tight closeups on marionettes’ heads, but Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s realisation in miniature of a post-scarcity future, filled with vast, shining feats of engineering, is difficult to resist, and Barry Gray’s celebratory score lends it a real sense of big screen solemnity. After this, the optimism of Gerry Anderson’s sci-fi quickly soured as the Space Race ended and middle-age approached, culminating in his comparatively pessimistic series Space: 1999 (1975-77).