Without question, Martin Scorsese is one of the most beloved and influential filmmakers of all time. His consistency of excellence throughout six decades of directing is impeccable. Because of his preservation and advocacy of the film medium, Scorsese has maintained a high status of relevancy unparalleled for filmmakers. Across 40 narrative and documentary feature films, he has made undisputed classics, but he also has under-the-radar gems in his resume.

1. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Martin Scorsese has faced criticism over the years for his lack of female representation and stories centered around women. While he is certainly a filmmaker interested in stories from a male perspective surrounding issues of masculinity, the idea that he doesn’t care about women, or that he isn’t responsible for riveting female characters is fraught. If anything, the director is always interested in learning more about personal blindspots, which is exactly why he decided to accept an offer from star Ellen Burstyn to direct Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

Scorsese’s film about a single mother, Alice (Burstyn), who travels cross country searching for a fresh start in life after her husband dies is one of his most human and grounded portrayals of a conflicted protagonist. Thanks to Burstyn’s incredible Oscar-winning performance, the film ceases to operate on a black-or-white basis. Alice longs for independence, but simultaneously, she can’t help but be tempted by life with a new husband. Staying true to the grain and moral complexity of New Hollywood ‘70s cinema, Alice is not afraid of confrontation, awkward emotions, and ambiguity.

The film manages to carry the same weight as Raging Bull or Goodfellas without overcompensating the protagonist’s plight. Scorsese’s underground rock-and-roll filmmaking established in Mean Streets is quite prevalent. The director walked the thin line between employing his natural artistry and adapting to a new story and environment. His sympathy and admiration for the titular Alice is palpable. Scorsese making more films like Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore would be welcomed greatly, especially to demonstrate his nuance and versatility.

2. New York, New York (1977)

Following the critical acclaim of Taxi Driver, Martin Scorsese was set to continue his inversion of cinematic ideals. With the divisive revisionist musical, New York, New York, the director took a big swing. While many find the film disjointed, and it certainly whiffs on many of its power swings on occasion, it is an endlessly fascinating text to analyze. The 1977 film and its subsequent audience disappointment led the director to question his motives and place in Hollywood.

New York, New York, a manifestation of New Hollywood sensibilities integrated into MGM classic musicals, follows an egotistical saxophone player, Jimmy Doyle (Robert De Niro), and the rocky personal and professional relationship with lounge singer Francine Evans (Liza Minnelli). Scorsese’s decision to place a downbeat love story against the backdrop of post-war Americana is quite interesting. The uncanny style of the film, featuring a set resembling an old studio backlot, is essential in creating the unglamorous vision of Scorsese’s tale of two dedicated artists who can’t express healthy love for each other.

The director’s admiration for the genre is evident, but he never holds back from crafting a grainy depiction of what usually is a home of jubilated movie magic. The Jimmy Doyle character is actively unlikeable–turning off many viewers, but the film’s unflinching characterization parallels the gloomy mindset of Scorsese at the time. New York, New York engages in an often convoluted juggling act with its themes, and it tends to grow weary and dull. This is the only instance in Scorsese’s career where his ambition got to the better of him. Major flaws aside, Scorsese’s musical, with its intersection of Hollywood history and ‘70s social turmoil, is worthy of a viewing.

3. The Last Waltz (1978)

Unbeknownst to casual observers, Martin Scorsese is an active documentary filmmaker. He is also an avid fan of classic rock and roll. The use of rock in his films is prevalent and widely celebrated, as his curation of pop music beautifully meshed with his stories. These passions converged to create The Last Waltz, the director’s concert documentary tributing The Band in its final performance. A soulful and touching depiction of a swan song, Scorsese’s heart is all over the stage as much as the rockstars.

Cross-cutting between The Band’s concert on Thanksgiving 1976 and behind-the-scenes interviews with band members, the 1978 film explores the interactions the music generates on stage and focuses deeply on the nature of friendship and harmony channeled through their music. Scorsese assembled a collection of the finest cinematographers and camera operators working at the time, including Michael Chapman, Vilmos Zsigmond, and Laszlo Kovacs, to precisely capture the most finite details–by proxy enhancing the beauty of rock and roll.

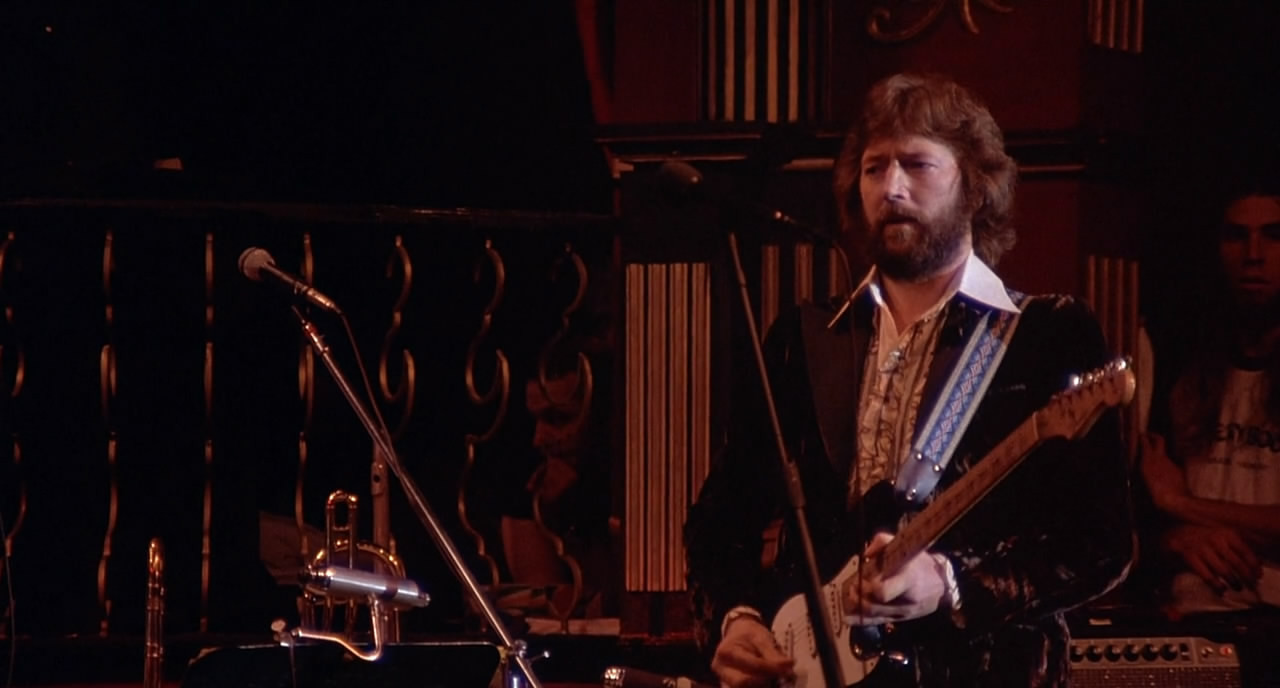

From the “this film should be played loud” title card to the intimate setting created by the camera on and off stage, The Last Waltz is rock and roll transformed into film. Each sound and patiently-drawn images are magnetic. Scorsese employs the iconography of famous guest performers at the concert, such as Bob Dylan, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton, Neil Young, and Joni Mitchell, to an honorable degree. The film reckons with nostalgia, legacy, and authorship. The candid interviews between members of The Band stay true to the director’s grounded authenticity. One of the most brilliant artistic choices of Scorsese’s career is restricting the camera to only capture the stage, and never showing the audience, leaving The Band on an island like mythical beings.

4. The King of Comedy (1983)

Recently a major influence on a franchise blockbuster in Joker, Martin Scorsese’s overlooked at the time, but recently reclaimed satire, The King of Comedy, ranks among the finest of his work. A downbeat film from 1983, a cinematic period ruled by populous entertainment, this is a continuation of the director’s exploration of the souls of broken people, and what depths they submerge to for the purpose of redeeming themselves. With this film, Scorsese has something biting to say about society and was more prescient than anyone could have imagined.

The story of The King of Comedy centers around Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro), a wannabe stand-up comic who stalks famous late-night host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) and eventually kidnaps him in pursuit of claiming overnight fame. What makes Scorsese’s film so brilliant is that it is just as bleak and cynical as Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, but the film just pretends it isn’t. The hallucinogenic and operatic visual language of his previous films is stripped away. In The King of Comedy, there is a sense of the ordinary. Rupert Pupkin exists in everyday life.

While still composed of intuitive cinematography and shot selection, Scorsese is purposefully non-flashy in its style. Whereas Travis Bickle and Jake LaMotta are reprehensible tragic figures, Rupert is likable. His showman quality draws the viewer to root for his quest to become a stand-up comic. This is where Scorsese pulls the rug out from viewers as his quiet sociopathic tendencies slowly unravel. The fact that he never breaks from his benevolent personality only heightens the psychotic nature of the protagonist. Ultimately, The King of Comedy dishes out harsh commentary on celebrity obsession and society’s glorification of crime. Rupert, an average-at-best talent who makes it big, is never punished for his crimes, but rather, he is celebrated by culture. In an age dominated by reality T.V. and exploitive true crime, this idea certainly packs a punch today.

5. After Hours (1985)

After the box office calamity of The King of Comedy and the cancelation of The Last Temptation of Christ, Martin Scorsese needed to hit the reset button. He needed to truncate his filmmaking back to his indie roots. Luckily enough, a clever script came into his sights, and was able to reinvigorate his style and thematic devices, creating the gonzo After Hours in 1985. With a simple premise rounded out by a cast of under-the-radar stars, this film ranks among Scorsese’s finest work, backed by incredible visual storytelling and subtle integration of the director’s frequent themes.

In this Kafkaesque nightmare, yuppie word processor Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), travels out to the neighborhood of SoHo for a night out, and through a string of misunderstandings and mishaps, he is unable to return home. From the eerie portrait of New York to the fear of unknowability, the film closely resembles a nightmare. Paul is like a rat trapped in a maze–all because he wanted to spice up his life by going into this trendy neighborhood for a date.

On the page, After Hours is played straightforwardly thematically. In actuality, Scorsese dissects man’s subconscious concerning sex. His draw towards various blonde women that he encounters on his terrible night rather than making his escape from the neighborhood indicates such feelings. Additionally, there is a reading on the film that centers around sadomasochism. This punishment handed out by the SoHo community is what Paul desired all along. After Hours has a personal connotation with the director, as the manic depiction of a person stuck in a never-ending cycle of misfortune had to have hit home for Scorsese when The Last Temptation of Christ was taken away from him. Even when the film is operating like a screwball comedy, the typical despair commonly found in Scorsese’s filmography is omnipresent here.