6. Lisztomania (Ken Russell, 1975)

Unbridled cult genius Ken Russell followed his rock opera Tommy (1975), a collaboration with rock band The Who, with the lesser-known Listzomania, another vehicle for The Who’s curly-haired, leather-lunged singer Roger Daltrey.

Taking Tommy’s highly-charged rock opera aesthetic into new territory, Lisztomania is a highly stylized and irreverent biographical take on the life of nineteenth century Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (Daltrey). Blending historical facts with fantastical elements, the story delves into Liszt’s relationships with various women, including his muse and lover, played by Sara Kestelman, and his rivalry with composer Richard Wagner, who is here portrayed as a vampire. The film skewers everything from silent movies, Superman (in both the comic book and Nietzschean senses), organized religion, Romanticism, and rock music. The influence of Russell’s freewheeling approach to historical events can be seen in the recent Babylon (Damien Chazelle, 2022).

Blending rock music with classical compositions (realized by Rick Wakeman, who also appears as Thor) and wild, cartoonish visuals. Listzomania is an ostentatious assault on both senses and sensibilities. It’s also a divisive film, partly due to Russell’s mix of fact and fiction. It’s certainly true that some of the comedy falls flat, such as the irritating hoe-down near the start, but “Listzomania” remains not only an influence on the music video aesthetic of the 1980s, but an audacious exploration of creativity, fame, and artistic passion, and a testament to Russell’s belief that classical composers and musicians were every bit as debauched, bombastic, and conflicted and as the rock musicians of the 60s and 70s counter culture.

7. The Whole Shootin’ Match (1978)

Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match is an authentically made and oddly charming film that captures the spirit of friendship and dreams in the face of adversity. The film follows the lives of Loyd and Frank, played by real-life friends Lou Perryman and Sonny Carl Davis (later to appear in Charles Band’s oddball Evil Bong film series). These are two blue collar Texans striving to achieve a better life through their entrepreneurial endeavors. When their roofing business fails to make money, Loyd invents a gizmo called the “Kitchen Wizard”; a three-in-one mop, vacuum cleaner, and floor polisher. Though they are paid an advance, they soon find reality getting in the way of their dreams of wealth.

With its naturalistic dialogue, improvised feel and beautiful 16mm photography, the film’s creation mirrors the DIY approach of its protagonists: Pennell and co-writer Lin Sutherland raised $43,000 by themselves to make this labor of love. The camerarderie between Loyd and Frank is genuine and touching, but the film doesn’t shy away from showing their unpleasant sides, and is unflinching in depicting them at their lowest and most vulnerable points too.

The film holds historical significance as a pioneer in the independent film movement in Texas. It paved the way for subsequent indie successes from the region, most notably the earlier work of Richard Linklater, whose Slacker is partly inspired by The Whole Shootin’ Match’s loose “hangout” feel. Perhaps more importantly, Robert Redford saw the film and was inspired to start the Sundance Film Festival. Pennell never had the kind of career that his formidable talent deserved, and struggled with alcohol and drug addiction for much of his life. The Whole Shootin’ Match stands not only as a testament to his talent and determination, but to the power of low-budget films in revealing the struggles of ordinary people.

8. Radio On (Chris Petit, 1979)

Something of an oddity within British cinema of the era, first-time director Chris Petit teamed up with Wim Wenders (acting as associate producer) and borrowed his assistant cameraman Martin Schäfer for this introspective tale of Robert, a radio DJ journeying from London to Bristol upon hearing the news that his brother has committed suicide.

Much like Wenders’ films of the period, the film is a road movie, taking place in anonymous hotel rooms, service stations, and gloomy pubs, all given an eerie beauty by the stark black and white cinematography that recalls the photography of John Davies and the melancholy sadness of Edward Hopper’s paintings. Radio On depicts the last remnants of an older Britain (the radio station Martin works for is based on the United Biscuits Network, an internal radio station that provided music for the workers of United Biscuits factories) about to be transformed by the twin forces of punk and Thatcherism.

The film is less about Martin finding the answers he wants, and more about the characters that he meets on his journey: a soldier traumatized by his experiences during the ongoing Troubles in Northern Ireland, a woman from Germany searching for her child, and an oddball rockabilly enthusiast (played by rock star Sting, who also appeared in the cult film Quadrophenia that same year) who lives close to the site where real-life 1950s rocker Eddie Cochran was tragically killed in a car crash.

The film’s soundtrack is of particular note, with its heady mix of Berlin-era David Bowie, krautrock, new wave, and pub rock of the era. The music underscores the fact that a film that must have had the immediacy of journalism on its release now reflects a forgotten everyday past. Radio On is a uniquely European and a uniquely British take on the road movie.

9. Driller Killer (Abel Ferrara, 1979)

Often miscategorized as a horror film, Driller Killer was added to the so-called ‘video nasties’ list in Britain, in part due to a garish and gory VHS cover. The film is in fact a raw and controversial film that is much No Wave as it is horror. The film begins with a title card that says: “This film should be played loud.” The story then follows struggling painter Reno as he gradually descends into madness, driven to murder by his financial and personal worries, and by the incessant noise of grimy late 70s New York city – including a punk band that move in nearby and torment him, rehearsing with their endless “oopshadoobay” refrain.

The film’s unfiltered portrayal of urban decay is both disturbing and evocative, capturing the seedy underbelly of New York. Reno’s solution is nihilistic: he doesn’t attempt to fight back at the forces oppressing him, he punches (or should that be drills?) downwards, murdering homeless men for a cathartic, amoral release. The film’s blood-drenched moments are all the more effective because the viewer is plunged so fully into Reno’s unhinged world.

Many of the performances are off-kilter and campy, and together with the room tone of the directly-recorded dialogue, this recalls the work of cult schlockmeister Hershell Gordon Lewis. Abel Ferrara both directs and stars as Reno, in an undeniably egotistical howl of anger. Cult author D.A Metrov also appears as the obnoxious Tony, the lead singer of The Roosters, and his paintings are seen throughout the film. Metrov and Ferrara later fell out, with Metrov calling Ferrara “The Piltdown Man” in his unusual Roman à clef Anatomy of a Werewolf. But whatever the personal feuds of the film’s creators, Driller Killer stands as another American nightmare, an unflinchingly personal portrait of No Wave-era New York splattered with gore.

10. Dirty Ho (Lau Kar-leung, 1979)

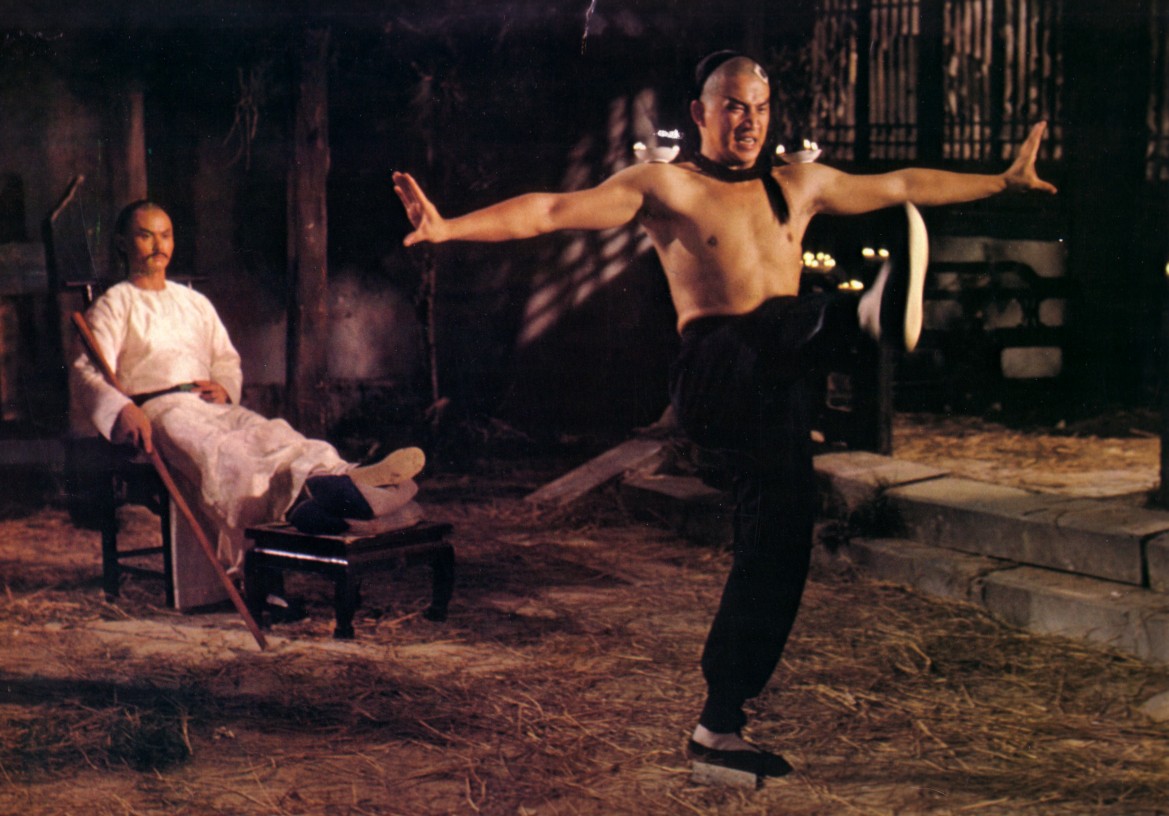

Kung fu films of the period often position China’s Manchu dynasty as the villians, but Dirty Ho is unusual in that its protagonist Prince Wang (played by cult star Gordon Liu) is an heir to the Manchu throne travelling incognito. Wang meets a clueless crook – the eponymous Dirty Ho (Wong Yue) – a comedic troublemaker who Wang trains into a highly-skilled fighter. The two form an unlikely partnership, teaming up to find out who is trying to have Prince Wang assassinated.

As the kung fu genre’s primary purpose is to deliver expertly choregraphed fight scenes, Shaw Brothers films of the period often have unimaginative, sterile sets whose purpose is to be unobtrusive. Dirty Ho, however, pulls out all the stops to create an unrealistic but stylized world of sleazy brothels, ruined cities, and ornate palaces. The mixture of lightning fast violence and broad comedy is brilliantly balanced, with Ho’s obliviousness to Wang’s fighting skill and true identity a wonderful comic device.

Then there are the action sequences, which are endlessly creative: in one early scene, Wang pretends that a woman is his bodyguard, manipulating her like a marionette and making her fight with Ho. In another, a tasting of traditional Chinese wines becomes a deftly choreographed battle, while Ho remains oblivious to the danger all around. As they travel to Peking (modern day Beijing) for an audience with the Manchu Emperor, they battle with “The Seven Bitters of the East River”, assassins whose campy, effeminate behaviour is far from politically correct, but is in step with the raucous carnivalesque humour of the director: Lau Kar-leung, is best known for the alcohol-drenched Jackie Chan comedy The Legend of Drunken Master (1994). Dirty Ho is an outstanding kung fu film that deserves to be widely known as a cult classic.