The 1980s were an exciting, transformative decade for cult cinema, One of the most significant changes was the advent of home video technology, which allowed audiences to access and enjoy movies in the comfort of their homes. Video rental stores became communcal spaces for fans to enthuse about their favourite films against a backdrop of colourful videotape covers and posters. This new accessibility not only broadened the reach of cult films but also gave unconventional works a chance to find their niche following. Cult classics like The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1981) found their devoted fan bases through home video.

In the UK, a moral panic grew up around this unregulated access to potentially disturbing content, and a list of so-called “video nasties” was drawn up that authorities believed had violated obscenity laws. The law of unintended consequences meant that this controversy only served to elevate the status of these films, making them even more appealing to audiences seeking subversive content.

Independent filmmaking thrived during this era. Directors such as Jim Jarmusch, Alex Cox, and Susan Siedelman took an uncompromising, DIY approach, one that perfectly encapsulated the frustrations of the era’s youth. Festivals like Sundance had the specific remit of promoting independent film and made it a recognizable category.

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, action-packed heroic bloodshed films such as A Better Tomorrow, which showcased stylized action sequences but also dealt with deeper themes such as fraternal loyalty and the double binds of colonialism. These films would be massively influential on American cinema, from Reservoir Dogs (Quentin Tarantino, 1991) to The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999)

In Japan, film also expanded because of more accessible formats: home video allowed for an explosion of original video animations that helped to make anime part of global popular culture, while 16mm film allowed directors such as Shinya Tsukamoto to realize intense, tactile cyberpunk visions.

All over the world, the combination of television and video technology allowed for greater access to films of the past, leading to the creation of new hybrid styles – films such as Society (Brian Yuzna, 1989) harked back to the horror of the 1950s but imbued it with a scathing, modern sensibility. Filmmakers could pay homage to the past while pushing creative boundaries.

Taking in horror, science fiction, and the downright unclassifiable, here are ten great 1980s cult movies you probably haven’t seen.

1. Wolfen (Michael Wadleigh, 1981)

Wolfen is a slow-burning blend of police procedural and horror that that offers a unique take on the werewolf genre. Released in 1981 and directed by Michael Wadleigh (better known for the epic 1970 documentary Woodstock) the film takes its audience on a chilling journey through the cold, garbage-strewn streets of New York City. Unlike traditional werewolf tales that center on an everyday protagonist’s transformation into a supernatural creature, Wolfen begins with a disillusioned former New York police captain (played by Albert Finney) being brought back into the force to investigate the gruesome murder of a property magnate, plus his wife and bodyguard. Left wing radicals are suspected, but when a homeless man and a construction worker are soon slaughtered in a similar style, he begins to suspect that the killings may be connected to a supernatural force.

Finney is suitably gruff and grizzled as Dewey, a burned-out protagonist disillusioned by life in New York and not ready to accept the existence of an ancient power. Virtuoso tap dancer Gregory Hines also appears in an unusual role as a coroner, and cult star Edward James Olmos (probably best known to movie fans as Gaff from 1982’s Blade Runner) appears as Eddie, one of the Native American workers who have a mysterious connection to the killings. Though the performances are indeed fine, this is a film where the primary concerns are its chilling atmosphere and interesting take on its themes.

The use of infrared photography to simulate the wolfen’s point of view is innovative and would later be taken up by better-known films such as 1987’s Predator. But most significant is the film’s atmospheric portrayal of early 80s New York. Critic and theorist Evan Calder Wlliams, in his seminal book Combined and Uneven Apocalypse, highlights the fact that the film has a documentary aspect – the film doesn’t reconstruct urban decay on a set, it was shot on location, testifying to just how derelict New York had become by the early 80s. The film offers a slick gentrification that would push out original residents on the one hand, and the ancient, primal force of the wolfen on the other. Wolfen does require a little patience, yet it’s a thought provoking and atmospheric contribution to the horror genre.

2. Smithereens (Susan Seidelman, 1982)

Smithereens, released in 1982 and directed by Susan Seidelman, is another shot-on-location portrait of urban decay in New York, this time focusing on the city’s already waning punk scene. The film follows Wren, played by Susan Berman, a narcissistic, deeply unlikeable – yet always compelling – young woman determined to make a name for herself, pinning up posters of her face all over the city. As she navigates the world of lower east side squats, raucous gigs, and disappointing men, Smithereens paints a vivid picture of youthful aspirations meeting cold hard reality.

Better known for the uproarious Madonna vehicle Desperately Seeking Susan, Siedelman shot this, her first feature film on 16mm, sometimes without location permits. She co-wrote, produced and edited the film, making it a truly personal project. The film was shot by the brilliant and underrated Chirine El Khadem who undercuts Siedelman’s sense of humour with a bleak sense of place.

The film’s raw and unpolished style mirrors the energy and disillusionment of the era it portrays. El Khadem’s cinematography captures the chaotic rhythm of the city and its characters, creating an atmosphere that – like its protagonist – is simultaneously chaotic and weirdly alluring. It’s not surprising that El Khadem would have such a keen sense of rhythm, as one of his other projects was inventing a polymetronome. Susan Berman’s performance as the self-absorbed and narcissistic Wren is remarkable, while Brad Rinn is brilliantly hapless as Paul, a young man who comes into Wren’s orbit. In an ideal world we would have seen more work from these fascinating personalities.

As a time capsule of a specific cultural moment, the film is fascinating, though the implication of a relationship between the punk scene and the selfish individualism of the 1980s may be uncomfortable for some die-hard punks. Smithereens is bracingly nihilistic, but somehow playful and fun too.

3. Gothic (Ken Russell, 1986)

Gothic, directed by cult legend Ken Russell and released in 1986, is a haunting and surreal exploration of the lives of some of literature’s most iconic figures. The film gives a fictionalized account of a night in 1816 when Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and others gathered at the Villa Diodati and engaged in a ghost story competition that would inspire Mary Shelley’s creation of Frankenstein. For the scriptwriters of the 1930s, Frankenstein was a moral tale about being punished for daring to play God – but Russell understands Frankenstein as a product of Romanticism: nature worship, existential terror, and debauchery are the order of the day.

The performances are compelling, with Gabriel Byrne’s haughty portrayal of Lord Byron and Natasha Richardson’s keenly intelligent depiction of Mary Shelley being particularly noteworthy. The cast’s chemistry is perfect for this claustrophobic setting, filled with artistic and romantic tension and paranoia.

The film’s strength lies in its creation atmosphere imaginative visuals. Russell’s direction takes the audience on a journey into the minds of these literary giants, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy. The nightmarish sequences are both disturbing and captivating, capturing the essence of the Gothic and Romantic movements. The film is not always a smooth watch: the imagery of miscarriage is important to understanding Mary Shelley’s troubled life, but is not for the faint-hearted. Meanwhile the cacophonous score from Thomas Dolby and the claustrophobic atmosphere of the Villa Diodati create an assault on the senses that can be overwhelming at times.

While Gothic is inspired by Frankenstein, it is by no means a traditional horror film, but nor is it a traditional biopic. Compared to the disappointingly prosaic Mary Shelley (Haifaa al-Mansour, 2017) this is a complex tribute to the woman who kick-started horror and science fiction with her visionary novel.

4. Walker (Alex Cox, 1987)

Director Alex Cox is well known for his cult hits Repo Man (1084) and Sid and Nancy (1986), but his lesser-known film Walker is every bit as impressive. Walker uses the real-life figure of William Walker, a nineteenth century mercenary who was hired by the US government to take over Nicaragua, and who proclaimed himself ‘president’ of that country to comment on modern day US/Latin American relations. A darkly comedic deconstruction of imperialism and political ambition, Walker mixes fact and fiction in a way that would make Ken Russell’s head spin, gradually bringing in twentieth century anachronisms such as telephones and helicopters to suggest that the 1980s US involvement in Nicaragua had a long-standing precedent. While it was Democrat Franklin Pierce who recognized the legitimacy of Walker’s Nicaraguan government in 1856, by the 1980s it was Ronald Reagan’s Republican administration secretly funding right-wing guerrillas there.

For all the anachronistic pop music and irreverent humor, Walker is deadly serious about brutal colonial exploitation. For all its strident left-wing politics it is still a nuanced film: Walker himself is humanized even though Cox has nothing but contempt for his political and military actions. The scene in which Walker has a long conversation in sign language with his fiancée Ellen (played by hearing-impaired actress Marlee Matlin) is simply beautiful, and undercuts Walker’s later descent into megalomania. Ed Harris brilliantly portrays Walker’s intelligence and ruthlessness.

Cox often attributed his unapologetically leftist take on Latin American issues as the reason for his becoming persona non grata in Hollywood. It’s quite likely that the end credits – a montage featuring news footage of President Reagan and the corpses of people killed by the contras – ruffled quite a few feathers. Cox would not work in Hollywood again, and his next uncompromising film El Patrullero (1991) would be made in Mexico. Walker is a biting critique of American interventionism and the cult of personality, challenging viewers to reflect on the tragic and farcical repetitions of history. But it’s not just a political manifesto – it’s also a blood-drenched acid western in the tradition of Sam Peckinpah.

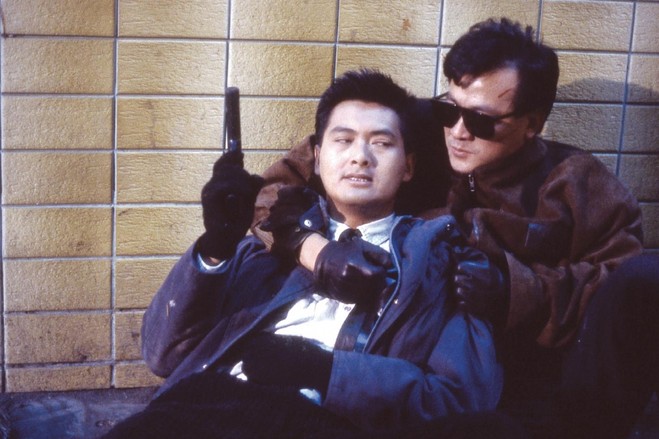

5. City on Fire (Ringo Lam, 1987)

City on Fire, released in 1987 and directed by Ringo Lam, is a gripping and intense Hong Kong crime thriller that is a landmark in the genre of “heroic bloodshed”: films that mix intense, violent action with themes of fraternal loyalty in a corrupt world. The film follows undercover cop Ko Chow (played by Chow Yun-fat at the height of his powers) as he infiltrates a gang of criminals planning a massive heist. His reluctance to get involved because of a past incident where he needed to betray a friend during an undercover mission perfectly highlights the tangled loyalties of the heroic bloodshed genre from the outset, while the shootouts are visceral and bloody, taking place on the cramped, neon streets of Hong Kong.

City on Fire is often referenced as an influence on Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs with certain scenes and themes echoing throughout the latter film. Some feel Tarantino’s homage verges on plagiarism. But this is heroic bloodshed, not one of Tarantino’s cynical homages. Lam’s characters aren’t expressions of 90s American slacker culture, they are bound by powerful loyalties in a pressure-cooker situation. The film took Hong Kong by storm, Lam and Fat followed it with a semi-sequel, Prison on Fire, that same year. School on Fire (1988) and Prison on Fire 2 (1991) soon followed. City on Fire has influenced countless films in Hong Kong and beyond, but nothing can compare to the original, deadly cat and mouse game of City on Fire.