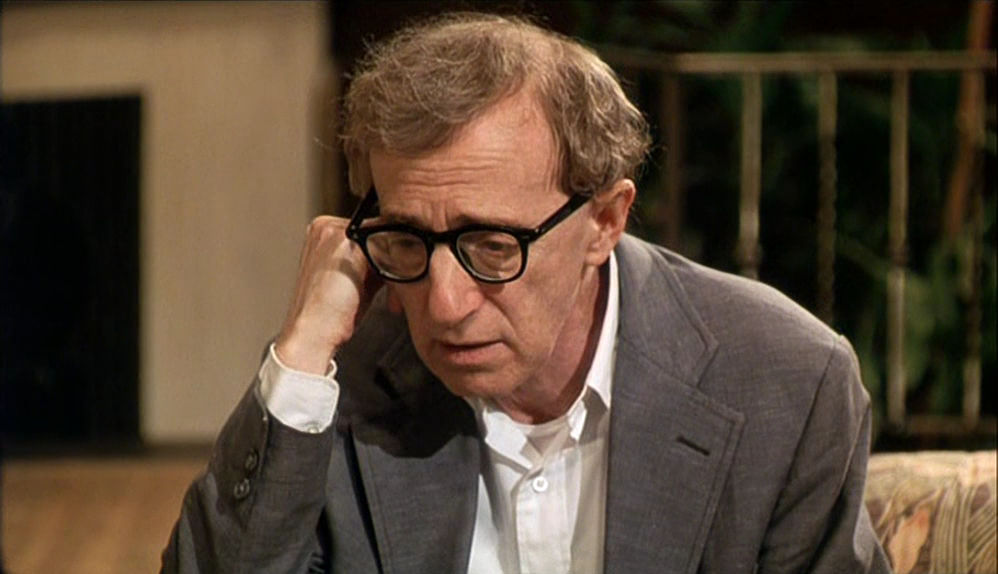

Woody Allen is one of the most acclaimed filmmakers of all time. His body of work has inspired countless writer-directors and many feel he’s made more masterpieces than any other film auteur. He’s won Oscars and critical admiration, is a darling to European cinema goers, and has been so for decades now. Films like Annie Hall and Manhattan were widely regarded as game changers upon their release in the late 70s, while Woody went on to make at least one film a year for the next forty, often taking the lead role in them. Even now, he is as prolific as ever, still working on film and book projects, as well as touring with his regular jazz band.

The Allen filmography is a rich and varied place. From broad comedies like Sleeper and Bananas to philosophical comedy-dramas such as Husbands and Wives and Crimes and Demeanours, there is a lot more to Woody Allen than a nervy neurotic dashing back and forth the New York streets. For every acclaimed classic, however, there are at least two more buried gems. Below, I have organised the ten directorial Woody Allen films I feel to be unfairly overlooked.

1. Love and Death (1975)

There is a subtle line in the sand moment with Woody’s 1975 film Love and Death, only the transition is so smooth and fluid that you wouldn’t have noticed it at the time. It’s where his great obsession, fear, stalker, and muse comes into the picture – Death. From here on in, after his string of madcap comedies, Woody seems to have been struck by the inevitable arrival of his own demise, and it creeps into nearly every picture. Of course, he had always feared it, even since his childhood, but now at middle age, he was feeling the Reaper’s icy hand closer than ever. Love and Death also shows for the first time his literary influences, in this case the heavy Russian books of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

Set in the Napoleonic era, Allen and Diane Keaton star as two Russians whose love is never fully fulfilled for a number of reasons. She is arranged to be wed to another, and Woody ends up fighting in the Russian army, becoming an accidental war hero in the process. (As he later would in the 1998 animated movie, Antz.) When the pair do do marry, after she becomes widowed, they are poor and pass the time by taking part in hilarious philosophical duels. When Napoleon invades, Woody decides to assassinate him, or at least to attempt to do so. Inevitably, Woody is executed. From beyond the grave he visits his love, accompanied by the Reaper, side by side with his great nemesis.

Love and Death is, under the surface at least, a weighty film lifted from weighty literature, though importantly you don’t have to have read every Russian classic to appreciate it. It was the closing chapter to Woody’s predominantly manic and wacky comedy era, though he would make a number of all-out comedies again over the next forty years. By 1975 he had become his own man, and though he had channelled Chaplin, Bob Hope, and the Marx Brothers, their influences were merely stepping stones to his own equally iconic persona and style. But that run of screwball comedies, starting with Take the Money and Run, is an unmatched series of cinematic joy. Comedy was just the springboard, and Woody would go on to explore many more things in the coming decades. Love and Death is often overlooked for this reason, given it bridges the gap between the two ages of his filmmaking career – all out comic to serious artist.

2. Interiors (1978)

Interiors is another giant leap for Allen in his career, for it marks the first time he fully entered the genre of drama, without comic undertones. It was also the first time he did not appear on screen in one of his own movies, choosing to stay behind the camera completely. Allen has said on numerous occasions that comedy was only interesting to him in his youth and younger professional years, but he found that it soon lost its appeal. “I’m serious nearly all the time,” Woody once said, and Interiors is certainly a serious film; perhaps his most serious film. At the time it wasn’t so well received, and at a budget of 10 million, it failed to totally ignite at the box office, though it did quite well in all. But Allen didn’t care, for Interiors had been a worthwhile experiment for him on a purely artistic level.

Interiors also signals another important breakthrough for himself and cinema. Allen has been acclaimed for his strong female roles, and his knack of creating real women on film seemed to really come to light on Interiors. Following three sisters – Diane Keaton, Mary Beth Hurt and Kristin Griffith – as their parents separate, Interiors explores the inner workings of a family unit, the rivalry and mixed emotions among siblings and the effects of a divorce on the children, no matter how mature they supposedly are. It’s a reflection of upper middle society (the father’s a corporate attorney and the mother an interior decorator) and the expectations of life within that framework.

The critics who dismiss the film as something with polish on the surface but nothing on the interior (no pun intended) seem to think the film was a transparent attempt for Woody to stop being “Woody Allen”, perhaps as a contrived escape from his own image. But as time would tell, Interiors was merely one side of the complex cube of his career. There are a multitude of moods in the Allen canon – comedic, surreal, drama, comedy drama, romance, even sci-fi – so to expect one thing from him is a fatal mistake. Interiors is too often overlooked if not completely ignored because it doesn’t have a single gag in it. But don’t let that put you off.

3. A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982)

After the heavy reception and critical hammering Stardust Memories received, Woody decided to lighten things up with his next picture, a breezy comedy and the first he made with his partner, Mia Farrow. Based on Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night, it’s a minor comedic work, and one that Allen tends to sideline a little as merely a bit of fun. In fact he often tends to do this in regards to all his light weight work, almost apologising for the fact that it doesn’t deal with more important themes. But the truth is we all need a bit of relief now and then, even Woody.

It was filmed at a custom built house in Pocantico Hills, and for the first time he set one of his movies in the countryside, a place Woody never really liked to visit much, with him being such a city person. Mia was of course the opposite and she had her own retreat country home which Allen rarely went to. “As a gesture of affection to her, I made a picture that embraces the country,” Allen said. “It’s meant to be beautiful.” And beautiful it certainly is, with the vibrant colours shining, glinting even, off of the screen. Though his follow up was already written, the complex and brilliant Zelig, Allen quickly wrote the script for Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy and decided to make it fast as a kind of break. In Woody Allen On Woody Allen, he states bluntly that he is under no allusion that this a great film. That said, it has its charms and many Woody die hards see it as an underrated gem.

4. Another Woman (1988)

Allen gets heavy with his ultimate Ingmar Bergman tribute, Another Woman, which is undoubtedly one of his heaviest dramas. Allen has often mentioned Wild Strawberries as a firm favourite of his, and here he lifts right from it. Gena Rowlands takes the lead role of Marion, a philosophy professor leaving work to write a book. Renting out a flat for some quiet time while construction work makes her home unsuitable for writing, she overhears a woman called Hope (Mia Farrow) being analysed by a therapist. The woman’s words – about her emptiness and phoniness – ignite something within Marion, who realises she too has been misguided in life and that many parts of her complacent existence are nothing but a lie, including her marriage.

Another Woman is a midlife crisis movie, pure and simply so, and it’s a picture I am sure many people in the midst of change can relate to. Rowland’s character is fifty (Woody was in his early fifties at this stage) and has clearly stopped to reassess her life and where she went wrong. It’s a valid subject. After all, just how many people, in the real world, have done the same thing?

Often totally overlooked, it boasts a fine supporting cast, which includes Harris Yulin and Gene Hackman.

5. Shadows and Fog (1991)

The word ‘forgotten’ may seem overly dramatic in regards to the film work of Woody Allen, unarguably one of the most famous figures in movies for the past fifty years, but for a man who has made so many high profile classics, acclaimed and revered all over the world, there are just as many that found themselves slipping through the cracks and entering the attic of minor obscurity.

Shadows and Fog is sadly one of them. Based on his rather strange and surreal one act play Death (that one title alone single handedly sums up the man’s huge career), Shadows and Fog stars Woody as another neurotic wimp, Kleinman. He is awoken one chilling New York night by a mob on a vigilante hunt for a serial killer, who has just taken another life by strangulation. Meanwhile, Mia Farrow and John Malkovich play Irmy and Paul, a pair of circus performers due to be married. After an argument, Malkovich storms off to the tent of tightrope walker Marie, (Madonna… who else?). Irmy catches her husband to-be about to have sex with Marie and flees for the big city, where she meets various colourful characters. Kleinman continues to hunt down the serial killer, and gets tangled in an increasingly seamy plot.

Shadows and Fog, despite its all star cast, sharp script and wonderful look, was one of Allen’s biggest flops, bringing back only 2 and a half million at the box office from a 15 million budget. Artistically though it’s a triumph and certainly among his finest and most underrated work. It deserves a dusting off, and I hope one day it gets its due credit.