Spain has a variety of unique filmmakers, but very few have resonated as profusely in the international film market as Pedro Almodóvar has. With 19 films under his belt, as well as awards from Cannes, Venice, and the Oscars, Almodóvar has crafted a reputation that is evoked by his often-used tagline: “A film by Almodóvar.”

His success is a result of his circumstances: he began making films during the transitory period between the death of Franco and the development of the progressive/transgressive la Movida. The establishment of Almodóvar’s company, El Deseo, ensured his autonomous power in the Spanish film industry, allowing him to develop a unique voice and provocative perspectives that would help create a new image for Spain.

With his tight-knit crew (including his brother, Agustín) and stable of actors (Marisa Paredes, Penélope Cruz, Carmen Maura, Cecilia Roth, and Chus Lampreave, to name a few), Almodovar seamlessly weaves international influence with a Spanish sensibility. His films have their own built-in film language and mythology, creating stories whose narrative trajectories are interconnected in one another. His films borrow heavily from the international language of melodrama, which is able to tap into emotions and images that speak volumes to those who may not necessarily speak Spanish.

This list looks at twelve of his most important works, which reflect technical, cultural, or personal landmarks for Almodóvar’s career. They range from his fun sex comedies to his more serious works, and everything in between.

12. Volver (2006)

Set in Almodóvar’s hometown of La Mancha (whose mechanized windmills evoke an industrialized image of Don Quixote), Volver follows Raimunda (Penélope Cruz) and her sister, Soledad (Lola Dueñas), who deal with the death of their aunt, Paula (Chus Lampreave). As Raimunda opens a secret restaurant and hides the rotting corpse of her dead husband, Soledad continues her illegal hair salon by hiring the “ghost” of her mother, Irene (Carmen Maura). Secrets are revealed, and the familial bonds that were once severed soon begin to mend.

Almodóvar blends neorealism with ghost stories in order to explore women who are unable to hide the skeletons in their closets. It is a continuation of his more serious works (which begin with The Flower of My Secret). This marks one of the first instances in which Almodóvar deals openly with the fear of sex, and it also marks the return of Carmen Maura, who haunted Almodóvar’s film canon during her 14-year absence.

11. La piel que habito (2011)

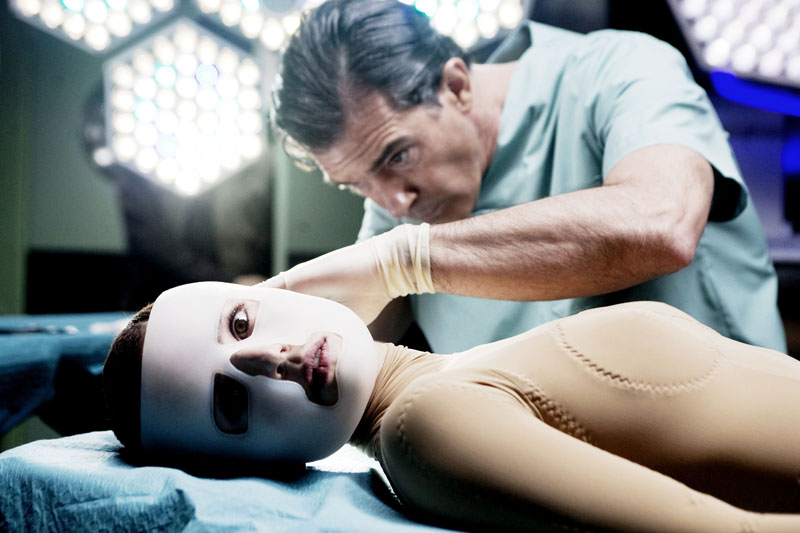

Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas) creates a durable skin that can resist burns and insect bites. He grafts it onto the mysterious Vera (Elena Anaya), a test subject who is held captive in Robert’s estate. The connection between two is ambiguous, but a series of flashbacks soon reveals their intertwined (and painful) pasts.

La piel que habito (The Skin I Live In) is a brilliant, if not tense, horror film that avoids any of the generic spooks and surprises. It explores how femininity is imposed on a person, utilizing images of patchwork mannequins and eerie masks (which evoke Edith Scob’s iconic mask from Eyes Without A Face). This is also the return of Antonio Banderas, who departed from Almodóvar’s work in hopes of finding a Hollywood career.

10. ¿Que he hecho yo para merecer esto? (1984)

Gloria (Carmen Maura) is a frustrated housewife who is stuck in a loveless marriage, works a tiring job, and lives in the confined tower blocks of Madrid. To make ends meet, she sells her son to a pedophilic dentist, sends her mother-in-law (Chus Lampreave) back to the village, and kills her husband (Angel de Andres Lopez) with a ham bone.

¿Que he hecho yo para merecer esto? (What Have I Done to Deserve This?) is Almodóvar’s first socially conscious film. It explores Gloria’s frustration through a neorealist lens, examining issues of gender and class while also showcasing Maura’s nuanced acting abilities (which would aid her in Almodóvar’s later, more polished works).

9. La flor de mi secreto (1995)

Leo (Marisa Paredes) is a writer who secretly pens “pink” novels under the pseudonym “Amanda Gris.” As she explores new avenues for her writing and tries to publish more controversial work, Leo discovers that her marriage is slowly disintegrating. Similar to her struggle to remove her husband’s military boots from her feet, Leo realizes that her relationship with her husband is a difficult obstacle to overcome.

La flor de mi secreto (The Flower of My Secret) is a fantastic film that delves into the story of a woman caught amidst dueling Spanish identities (one of which is grounded in romanticized history and military fetishism, while the other is longing for more gritty and passionate relationships). The film is credited as the beginning of Almodóvar’s mature/serious period, as well as being the first entry in Almodovar’s masterful “Brain Dead” trilogy.

8. Laberinto de pasiones (1982)

Sexilia (Cecilia Roth) is a nymphomaniac pop star who goes from orgy to orgy looking for pleasure. Riza (Imanol Arias) is a gay Middle Eastern prince who, while hiding in Spain from terrorists, conquers any and all men who tickle his fancy. When Sexilia and Riza unexpectedly meet, the two transform in order to please one another (Sexilia tries to overcome her nymphomania and Riza tries to become a heterosexual).

Laberinto de pasiones (Labyrinth of Passion) is one of the best examples of Almodóvar’s involvement in la Movida. His ability to depict a progressive/sexual image of contemporary Spain is coupled with his ability to create an intriguing portrait of two people who tap into their fluid sexualities. The underground tone of the film gives it a queer and kitschy sensibility, one that would be refined over the years for mainstream consumption. In my opinion, this is one of Almodóvar’s best sex comedies, which he tried (and failed) to recreate with 2013’s Los amantes pasajeros (I’m So Excited).

7. Matador (1986)

Diego Montez (Nacho Martinez) and Maria Cardenal (Assumpta Serna) fetishize violence and murder for sexual pleasure. Diego, who was injured from a bullfight, watches horror films in order to ejaculate, while Maria kills men and straddles their corpses. The meeting of the two becomes a meeting of like minds, and they plan to consummate their carnal desires during an eclipse.

Almodóvar’s controversial classic is a provocative take on Spanish culture, which itself fetishizes blood and violence through the figure of the matador. Though Almodóvar has stated that this is one of his two weakest efforts (along with Kika), it is still an interesting image of contemporary Spain crafting its own desires through its bloody roots.