Studies show that half of all film school graduates are women, yet only 5% of them are working Hollywood directors. This is not only a problem in Hollywood, but everywhere in the world. There’s prejudice and difficulties akin to them, common stories of declined financing help and even production interruptions due to certain chosen themes and subjects in their work.

There are exceptions to the rule that are forgotten, and others that are now breaking through. Although many who are active today seek refuge in independent filmmaking, TV and online media, they are – increasingly so – receiving more attention. The current list gathers some of the most prominent female filmmakers in the history of film, and the movies that made them so inspiring.

1. Triumph of the Will (Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)

A propaganda film considered by many as one of the best documentaries ever made, Leni Riefenstahl chronicles the 1934 Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, which was attended by more than 700,000 Nazi supporters. Riefanstahl won instant international fame with this and the other propaganda films she directed in the 1930s. She was considered a pioneer of film and photographic techniques; after she filmed Triumph, she was labeled by many as the greatest female filmmaker of the 20th century. Her personal association with Hitler (who actually commissioned this film) ruined her film career after Germany’s defeat in World War II.

In this documentary, Riefenstahl rehearsed some of the scenes at least fifty times, with the main theme being the return of Germany to power and Hitler as the leader who would bring glory to the nation. Popular in the Third Reich, Triumph has served as a true influence on all contemporary film genres and commercials.

2. The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953)

A pioneer among women filmmakers, Lupino became interested in directing in the 1940s. After being on suspension for turning down a role she began to explore filmmaking, the filming and editing processes, and what she called “the interesting work.” She became the first actress to produce, direct, and write her own films.

The Hitch-Hiker was her first fast-moving film, a film noir about two fishing buddies who pick up a hitchhiker while on a trip to Mexico. Based on the true story of psychopathic murderer Billy Cook, the two men must survive a hostage situation where escape seems impossible. (An incredible detail is that they are located in the desert, but are constantly confined to small spaces.) Arguably, Hitch-Hiker is Lupino’s best film, and the only true noir directed by a woman, with emotional sensitivity and class performances by the three protagonists.

3. Daisies (Věra Chytilová, 1966)

Chytilová wrote and directed this Czechoslovak comedy-drama film and turned it into a milestone of the Nová Vlna (Czech New Wave) movement, making it the second film by the only female in it. It follows the story of two girls named Marie who engage in a series of adolescent adventures. There’s really not much of a plot, as the director’s hand in it clearly wishes to make the film itself an experience, with brutally colorful imagery, random sequences with no apparent structure, music and sound often randomly appearing with no reasoning within a scene.

It is often a series of events mixed with philosophy, nonsense chattering. There are sudden alternations between black and white and monochrome filters of all colors, as well as standard photography. Even with the amazing surrealism and eccentric humor it brought, the film was labeled as “depicting the wanton” by the Czech authorities and therefore banned.

4. Seven Beauties (Lina Wertmüller, 1975)

In its original title, Pasqualino Settebellezze—starring Giancarlo Giannini, Fernando Rey, and Shirley Stoler—the film narrates the story of Pasqualino, an Italian man who, during World War II, abandons the army, is captured by the Germans, and sent to a prison camp. While doing everything he can to survive, the audience learns about his family—through flashbacks, specifically his seven unattractive sisters—and a few stories involving them and ultimately him.

After filming Seven Beauties Wertmüller, an Italian film writer and director, was granted the first female nomination for an Academy Award in Direction. The characterization, for instance, is astounding; Giannini presents the foolish side of his character and performs admirably. Gianni portrays a macho, opportunist man, deeply convinced he’s honorable. It is as black as comedies come, yet the audience is left with the notion that Wertmüller likes the unexplained, the irrelevant moral choices, and the mystery in her most memorable project.

5. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Chantal Akerman, 1975)

A clear dedication to the ellipses of conventional narrative cinema, Jeanne Dielman broke new ground and remains a narrative inspiration. Akerman claims that, after seeing Godard’s Pierrot le fou at age 15, she decided to pursue filmmaking. When Jeanne Dielman first debuted, The New York Times called it the “first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of cinema.”

The story examines a single mother’s life, cooking and cleaning over three days, while also prostituting in order to provide for her son. Prostitution is part of her routine, dull and uneventful like everything else in her life. The twist comes when the routine starts failing, and she spontaneously starts doing things she wouldn’t usually do. Akerman is brilliant in viscerally mixing these topics by using an innovative directorial approach, while leaving the audience with the task of filling the gaps.

6. The Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

Shepitko’s last film before her death was this black and white Soviet drama film—winner of the Golden Bear award at the 27th Berlin International Film Festival in 1977. Said to be one of the finest war films ever made, The Ascent is set in the bleak winter of 1942, during World War II, and follows two young Soviet partisans as they search for food in a Belarusian village, which was occupied by Nazis.

After being spotted by a German patrol, one of them is shot in the leg, and the other has to take him to a safe place: the home of a woman named Demchikha. However, they are discovered, and both the partisans and the woman are taken to the German camp for interrogation. The struggle of the proletarian is the key point in this story, and the film stands tall as a cinematic statement of politics, faith, and moral choices.

7. Vagabond (Agnès Varda, 1985)

Vagabond is a drama describing the story of a woman who, during one winter, wanders through the French wine country. A dark and disturbing grasp on the life of Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), told through flashbacks and a near-documentary style, including alternative interviews with the people who have known her in the last weeks of her life.

Throughout the film, the audience gets to know the main character, how she seems so independent and hard to love, drifting from place to place accepting any help or places in which to stay. No one really knows where she is from, or how she ends up in her situation.

It’s noticeable how Varda’s background as a still photographer finds a place in this film. It is a particularly moving grip on visual detail that takes the story to an even harsher reality while simultaneously supplying the necessary beauty.

8. Big (Penny Marshall, 1988)

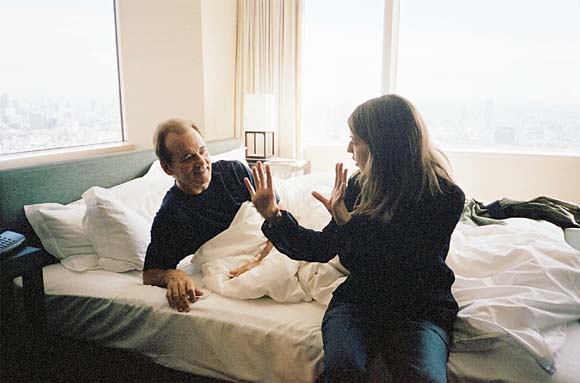

Starring David Moscow and Tom Hanks as 13-year-old and 30-year-old Josh Baskin, Big, in the “body swap” sub-genre, recounts the tale of a boy who makes a wish “to be big” and becomes an adult overnight.

At the start of the film, there are the usual jokes/issues applied to this sort of story (clothes not fitting, no one believing him, etc.), but it quickly falls in a deeper scenario. Josh clearly has no experience in adulthood, but it’s surprising how he can make it work.

Tom Hanks’ performance makes the audience believe he really is a 13-year-old boy trapped in an older body, and that is mostly because Penny Marshall made the two actors spend time together—even though they never shared a scene—and she had David Moscow them rehearse many of the grown-up Josh scenes performing the role, so Hanks could observe how the younger actor would react in those situations.