Science Fiction and VFX have long been the marriage required to keep both running at their full potential and capacity, but what if there were another means of crafting the visual splendour and lack of physical realisation that comes with the genre’s territory?

There is, but it happens to be also wholly expensive, and possibly doubly time-consuming and tedious: animation.

Animation is a truly splendid art, one that allows unrestrained fulfilment of all imaginative extents. It presents the ordinary into the emotionally and tonally distinct, and unlike filming in real life, animation provides no constraints as there are no confinements to limit one’s creativity.. Animation has long been considered, and resultantly dismissed, as a mere gimmick to attract children to appealing products, but the existence of worthy Disney titles rendered this belief inert.

Then came a point in twentieth century cinematic art wherein one man attempted to break some mould: the release of the first ever adult-oriented animated film for theatrical release. In 1972, Ralph Bakshi’s release of Fritz the Cat embraced, suffocated, and exploited its name as an ‘adult’ animated feature as much as possible (and it was glorious), making the existence possible of descending mature animated content for the cinema, Bakshi or no, far more feasible. Therefore, windows began opening for cinephiles to take animation as yet another cinematic form that was also thoroughly worthy of being made by grown-ups for grown-ups.

Exposure to Japanese anime, primarily during the 1990s, established certain Eastern individuals and collectives as giants with whom to be reckoned on the animation field. The West unconsciously countered with Pixar, abandoning the blatant violations of moral decency and family-friendliness succumbed to by anime required for purely mature viewing, instead focusing once more on a time once wherein children and adults could enjoy their animation equally.

An outline of some changing shifts regarding the production and producers of cinematic animation is key just for some background toward the different walks of life from which these animated sci-fi features originate. Perhaps as a weak means of tension as one reads the countdown, ponder which time and place, of which pencil-and-eraser filmic zeitgeist it a by-product?

Find out now, in this particularly personal listing of the greatest animated films belonging to the science fiction brand.

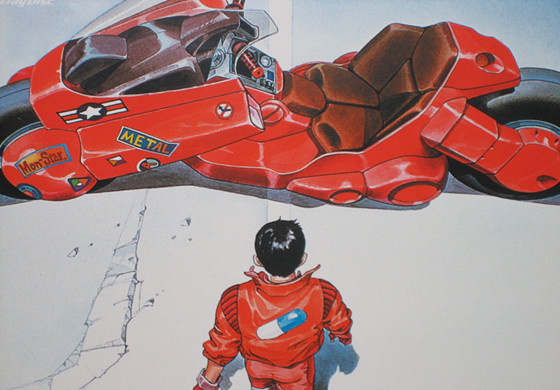

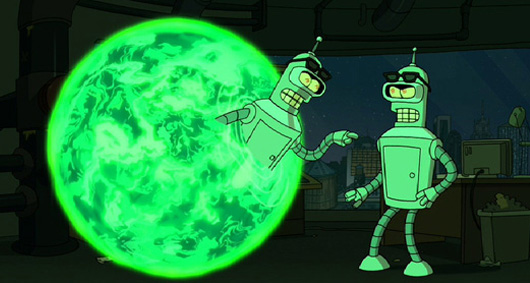

10. Futurama: Bender’s Big Score (Dwayne Carey-Hill, 2007)

Perhaps the peak of animated science fiction programs, certainly from the west, Futurama received a highly worthy comeback, following a dreaded four-year hiatus, in 2007: a direct-to-DVD paradox-spewing adventure known as Bender’s Big Score.

Truly, few better comebacks exist for a television program Bender’s Big Score identifies and proves its knowledge of the Futurama cast within minutes, explores long-hinted arcs and recurring character developments, provides a worthy narrative for a feature-length product, and is very funny to boot.

Once more, the writers of this show prove their extreme worth in tackling the often-ridiculed and amateurishly handled time travel subgenre, following season three’s classic, Roswell That Ends Well, to tell an intertwined, intricate tale of greed, love, determination, betrayal, stupidity, and growth. We wind up in one of the best stories the franchise has ever produced.

Three sequels were released, which collectively made up Futurama’s fifth season, but none held the perfect balance and charming courage that Bender’s Big Score was heavily prided upon.

9. Ghost in the Shell (Mamoru Oshii, 1995)

The first of two pivotal sci-fi anime films that is mentioned in most ‘best of’ sci-fi or anime movie lists, Ghost in the Shell is a film that some reasonably could claim is mostly a series of complex ideas, philosophies, and theories presented against the backdrop of the gorgeous animated cyber-Metropolis: a digital labyrinth Japan.Regardless, this doesn’t make Ghost in the Shell any less a unique, distinct piece of work that any fan of either sci-fi, anime, and especially (especially) both, ought to make mandatory, ASAP viewing.

Truth be told, while it is wholly true that the Wachowskis themselves garnered much inspiration from Ghost in the Shell when creating The Matrix, the existential, A.I. musing, crime thriller remains totally and utterly its own unique miracle in regard to sci-fi presentation and thematic substance for one of its bracket’s feature films.

In addition, an eclectic, moving and heavily impactful soundtrack further merits Ghost in the Shell as a fairly essential viewing.

8. Big Hero 6 (Don Hall / Chris Williams, 2014)

The most recent entry on this list concerns a strongly Japan-influenced San Francisco as the engrossing setting with which to set a contemporary Disney rendition of the superhero summer blockbuster. Well, of course it would: Big Hero 6 is based on a Marvel Comics property after all. It is less the utilization of superpowers and gadgets to quash an antagonist’s schemes, which makes the Big Hero 6 brilliant viewing for sci-fi animation fanatics, but rather how Don Hall and Chris Williams celebrate the ability of animation to nurture concerns of what a live-action film is capable of mystifying an audience.

Through this means of story presentation, the sky (or a large Disney budget and more than several rooms brimming with exquisite computer clusters) is the limit, as far as imagination stimulation goes.

Without the innovative feats in animation that have allowed 3D modelling to prosper as the dominant force in children’s entertainment production, the world would never witness the liveliness, and motorized soul, of the adored Baymax: one of the finest Disney characters in years.

Exploring the scenarios that a medical A.I. might be abnormally thrust upon, and how his inflatable exterior sees practical application and, therefore, audience intrigue, upon witnessing its potential, is effective, back-to-basics Science Fiction 101. The hypothetical, fantastical possibilities of science and technology are presented and ingrained within a narrative (a phrasing under which one could practically blanket the entire genre).

Also, anyone looking for an attempted merging point between Western and Eastern sci-fi animation may look no further. Disney’s recent, blatant attempts to incorporate elements and influences of anime physiology (e.g. the enlarged eyes of Rapunzel and/or Elsa) are no more evident than with their 2014 outing: a city drowning in Eastern culture, young people attaining powers beyond their measure or apparent responsibility, and a typical incorporation toward the kind of loyalty and honour-based moral substance that underpins both Disney and anime productions alike.

7. Wall-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008)

Undoubtedly the most popular and well-known title on the list, WALL-E is the most mainstream ‘slow,’ more artistically and intellectually inclined science fiction film ever created.

Well, at least for its first half.

Before it descends into an overuse of fat jokes clogging the full power of the picture’s message, WALL-E is a moving, powerful, memorable piece of animation. Through no dialogue–just images and noises–the establishment of the narrative is made perfectly sound and clear, plus, it progresses very smoothly to the extent where the film’s unique distinction of presentation gets taken for granted, forgotten. Considering how audiences gradually become used to WALL-E’s more unconventional means of storytelling is a clear testament to its aesthetic ability, and at Pixar’s grasp at appeasing both the masses and the more artistically inclined.

WALL-E is a special one, whether it is for its design of two of the most memorable movie robots, or for being upfront and unapologetic with its critique on detrimental human behaviour, or opening children a gateway, a shortcut, to eventually finding further appreciation in less flashy, fast-paced and over-the-top sci-fi.

Andrew Stanton is responsible for this, hopefully, eternal missing link between more sophisticated children’s sci-fi cinema, and the legendary sophisticated ‘adult’ sci-fi cinephile repertoire involving the likes of Metropolis, 2001, Solaris, and Blade Runner.

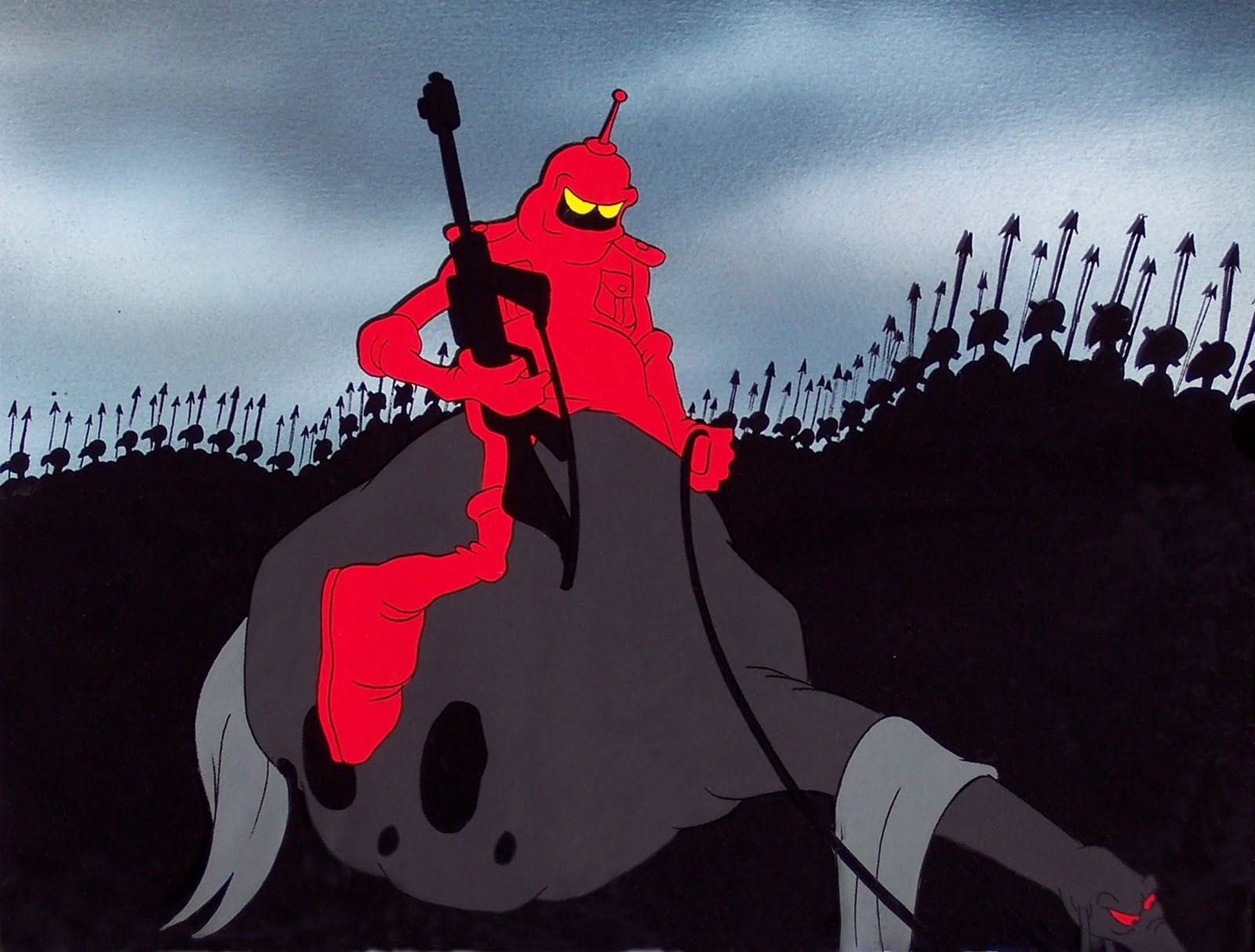

6. Wizards (Ralph Bakshi, 1977)

To be sure, this is arguably more of an inherent fantasy narrative than a science fiction one, but its setting on a post-apocalyptic Earth, with themes from typical sci-fi fare, such as freedom, totalitarianism, faith, determination, and murderous androids, make Wizards a feasible entry in this list.

Plus, let’s face it: the picture simply rocks!

Also, surely it isn’t any kind of stretch to deduce Wizards as the predecessor (intentional or otherwise) to two other, later, post-apocalyptic ventures on this list, accounting for some minute degree of importance to what isn’t necessarily one of Bakshi’s most widely acclaimed works.

Wizards offers some of the very best material one could ever gleefully expect from Ralph Bakashi, New York fiend: be it zany Jewish stereotypes, sickly comic attitudes toward sex, the lack of a protagonist’s morality, or, to top it all off, a hasty, rough means of animation to give the minor epic a surreal, engrossing flavour to call all its own.

Anyone who seeks to experience a strange, memorable, electrically entertaining, charming, humourous, and sadistic spin on the fantasy ‘good vs. evil’ quest requires a regular dosage of Wizards.