You’ve probably seen countless lists on countless websites dealing with this same topic using slightly different wording and you’ve probably noticed the same titles coming up over and over again. Indeed some ‘underrated’ or ‘forgotten’ sci-fi films are so often described as such that they’ve become the opposite. Coherence or George Lucas’ THX 1138 have found dedicated followings largely through online word of mouth.

To avoid falling into the same trap some very basic parameters have been set for a film’s inclusion on this list. To be considered overlooked the entries must have fewer than 50,000 audience ratings on IMDB (by comparison Inception and The Dark Knight both have over one million) and not be largely recognised as culturally significant.

For example, these conditions would consequently exclude Danny Boyle’s Sunshine, which although has been included on plenty of other similar lists its 169,000+ ratings on IMDB suggest it has found a significant fan base. Furthermore, Godzilla (1954) has just over sixteen thousand ratings but could hardly be described as underrated as it continues to be recognised for its influence through rereleases, sequels and remakes.

Finally these films have been chosen to represent the length and breadth of the science fiction genre. The list spans seven decades, seven countries and features Chinese superheroes, Soviet cosmonauts and Palme d’Or winners, moving through Canuxploitation, Left Bank New Wave and no small dose of Eighties’ cheese. If you think anything’s missing and want to big up one of your own personal favourites leave a comment and tell us what’s your ultimate overlooked sci-fi classic.

1. The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936)

A scientist descends further and further into insanity as his peers’ institutionalised foolishness leads him to be mocked and ostracised. A plot you’ve no doubt heard a thousand times and yet The Man Who Changed His Mind retains a certain uniqueness. Boris Karloff turns from creation to creator as Dr. Laurence, determined to prove he can transfer a person’s mind and consciousness from one body to another.

The physicality of the performance is almost lost amongst the expressiveness of the horror legend’s face, seemingly able to display desperation, cunning and eventually madness with the twitch of an eyebrow or a single lingering look. Add to this the bravery of Anna Lee’s Dr. Wyatt and pomp of Frank Cellier’s Lord Haslewood and the cast breathes dark wit and sinister drama into a concise sixty-six minutes.

The film is not without its flaws though, Laurence’s Ygor-esque subordinate Clayton promises us he has a “perverted mind” though is never given the chance to show just what hideous schemes he is concocting. Wyatt is built up as a determined intellectual woman, truly a rare breed in classic horror films, but then the script doesn’t seem to know what to do with her.

It’s difficult not to cringe as she chuckles at her male companion’s admission that he “hates strong-minded women.” However between the expressionist sets, prying yet never obtrusive close-ups and rhythmic tracking shots the camera doesn’t allow the audience time to dwell on such problems. It was for works like this that the cliché of the ‘forgotten gem’ was first conceived.

2. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954)

It’s difficult to describe a sci-fi literary classic being bought onto the screen with such dramatic and technical expertise as in Disney’s live action adaptation of Jules Verne’s seminal adventure novel without resorting to hyperbole.

Perhaps the greatest compliment to be paid is simply to say that between the cast of cinematic heavyweight champions and visual flair 20,000 Leagues does justice to its source material’s sense of exploration. It’s not perfect, being inevitably weighed down by its loyalty to the episodic structure of the novel, but the final product is admirable.

Breaking with some of the darker elements of the book, Kirk Douglas excels in joyous goofiness as Ned Land. Conversely James Mason’s turn as Captain Nemo is a much more psychological performance. The former brings a likeable charisma and the latter, as always, seems at his best with his enemies closing in.

Having said that the film is an exercise in thrilling escapades, complimented but not dominated by its characters. To bring that to life lavish set and costume designs put audiences inside the exquisite Nautilus and wonderful camerawork guides them through the deepest depths of the oceans. Having been remastered into High Definition but never re-released on Blu-ray it’s surely time to return, even if even Nemo doesn’t know just what might be waiting down there.

3. The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959)

When black miner Ralph Burton escapes the tunnel he has been trapped in for five days he emerges into an empty world. It seems the Earth’s entire population has vanished. He makes his way to New York and finds no-one, not a single soul. The tension borders on overwhelming. The unbearable solitude leads Ralph to ask if we “know what it means to be sick in your heart from loneliness?”

That will have to suffice as a synopsis as The World, the Flesh and the Devil has much greater questions and prior knowledge of the plot may serve only to weaken the sense of surprise as they are slowly posed.

Its title is drawn from the theological antithesis of the holy trinity, the three things that supposedly tempt people the most. However its most effective drama is drawn from much more tangible and material sources, namely the politics of race and gender. Does the destruction of a society necessarily mean the destruction of its prejudices?

Now Ralph wants to know “why should the world fall down to prove what I am and that there’s nothing wrong with what I am?” The continuation of humanity may depend on the answers given and their interpretation by those who are left alive.

Somewhere between Richard Matheson, Simone de Beauvoir and Rosa Parks, the film attempts to lift the world on its shoulders. For a great length of time it stands firm to its convictions with both feet planted firmly on the ground. However in the end it buckles under the weight of its own themes and resorts to reflecting rather than rebelling against convention. Although it ultimately settles for an unnecessarily amiable ending, it is certainly worth your time. Some of its questions though will require your own answers.

4. Mothra (1961)

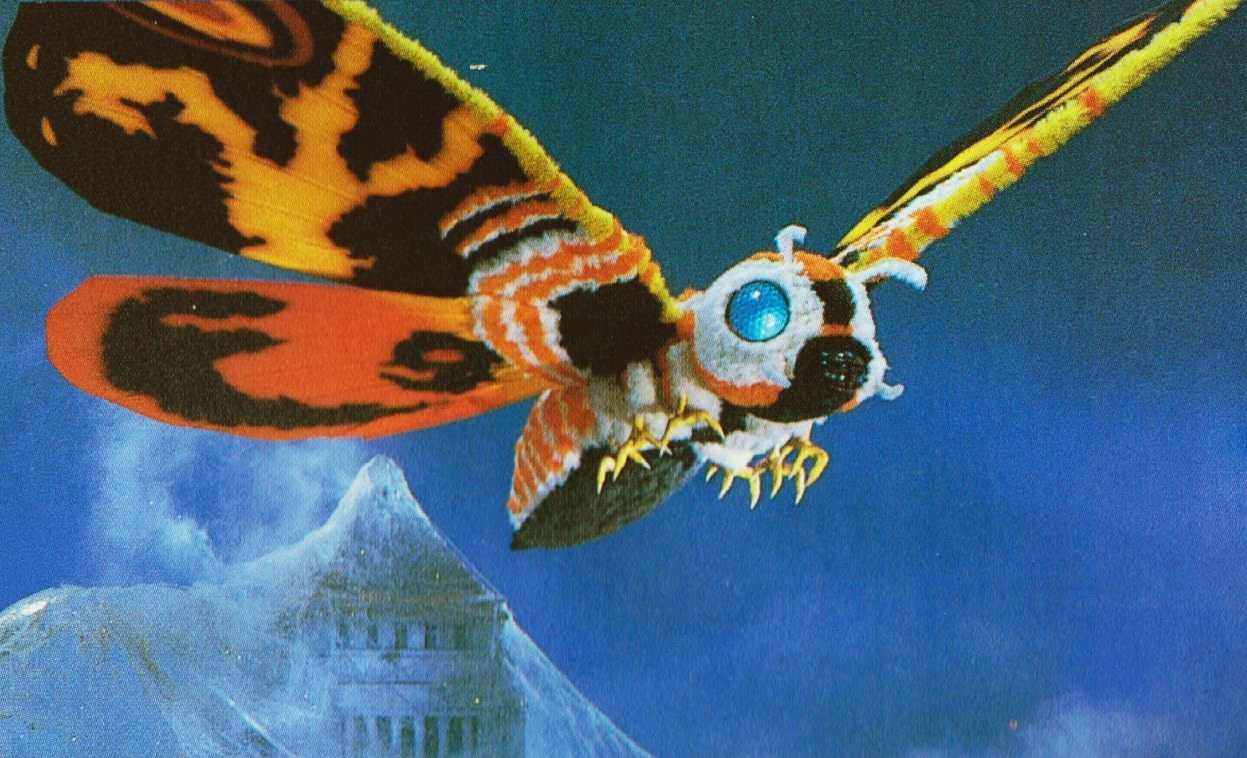

When an island previously thought to have been uninhabitable due to its proximity to Pacific nuclear test sites is discovered to be brimming with life, a greedy member of the resulting expedition kidnaps two of its 30cm tall natives. The ignorance of these self-proclaimed ‘civilised’ men soon leads to the awakening of a Toho legend.

Having starred in twelve films, fourteen video games and two comics Mothra can hardly be described as overlooked or forgotten. But the Divine Moth’s first film appearance has been somewhat overshadowed by her battles with the King of Monsters and an assortment of other Kaijus. Her self-titled debut however is worth revisiting as a frankly bizarre comic book of a film that proves cheesy and over the top need not mean meritless.

The anti-atomic sentiments of 1954’s Godzilla are recycled with mixed results. Focusing on the threat of annihilation faced by Polynesian islanders who live inside nuclear test zones was an intelligent move, having Japanese actors in blackface portray them as benighted was not.

The sense of post-occupation Japan hurtling into a new era while still at the mercy of global superpowers is conveyed well through Nelson, the film’s deviously greedy antagonist. He hails from Rolisica, an amalgamation of the USSR and the USA and with the backing of his government he acts with disregard for the sovereignty of other nations and survival of their people.

From its opening shots the film’s colour palette is striking and full of intensely saturated reds, blues and greens. It lends a sense of jovial absurdity to proceedings, highly appropriate considering the action involves international diplomacy, cannibal plants and fairies telepathically communicating with a giant moth.

5. La Jetée (1962)

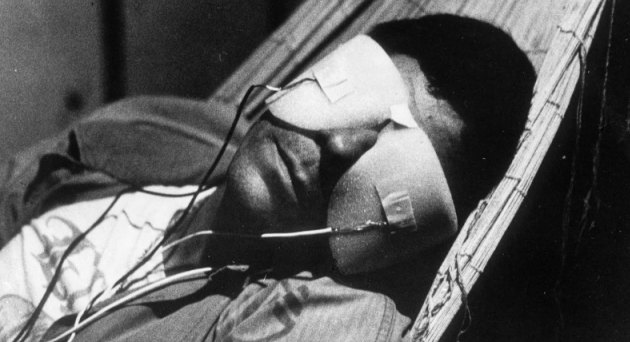

Describing a film as ‘an experience’ has become such a worthless cliché it’s barely worth typing and yet, if you’ll excuse the sensationalism, there aren’t many other ways to put La Jetée into words… a trance perhaps? Too vague. A reverie? Too pretentious. Clocking in at 28 minutes and comprised almost entirely of still images, here is a film that would not only inspire one of the most beloved modern sci-fi classics (12 Monkeys) but would – and continues to – influence generations of directors.

After World War III has left the surface of the Earth uninhabitable, survivors living under the streets of Paris experiment with time travel. Sinister scientists desperately transport potential saviours backwards and forwards “to call past and future to the rescue of the present.” Their latest test subject is chosen on the basis of the clarity with which he holds onto a pre-war memory in the hope that it will help him to withstand the mental toll of his momentous task.

Not in spite of but rather because of the fact the audience is practically watching a series of photographs with the barest of soundtracks, director Chris Marker is able to conjure a vivid, haunting daydream. Every frame is striking, each an aesthetic beauty appearing for a fleeting glimpse and then disappearing, only to be found later in some deeper cerebral recess like an epiphanic memory.

6. Creation of the Humanoids (1962)

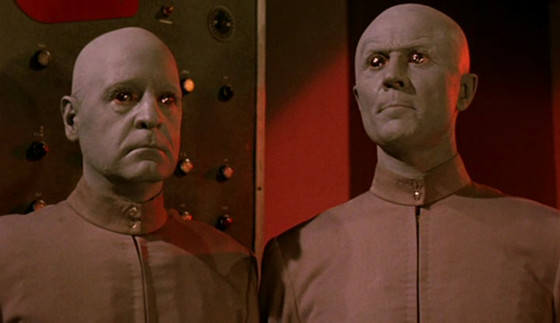

Rumoured to be Andy Warhol’s favourite film, Creation of the Humanoids begins after nuclear war has left a fraction of humanity alive and the survivors suffering from a catastrophically low birth rate. Efforts to reconstruct society are increasingly reliant on blue-greyish skinned unblinking humanoid robots.

Although considered second class citizens and limited to menial jobs their ever greater intelligence and emotional capabilities are perceived as a threat by some. The ultra-conservative paramilitary Order of Flesh and Blood seeks to deny them their already paltry liberties and campaigns for a more entrenched institutionalised form of anti-robot discrimination.

Steeped in the Civil Rights movement of the time, Creation is a film of ideas and presents its two cents on racial oppression with all the subtlety of a biology class with Dr. Frank N. Furter. Yet although certain scenes are weighed down by tedious dialogue and abysmal audio editing, the politics behind the script is enough to make the fictional universe engaging.

The society’s hypocrisies and prejudices are dissected through everyday scenes such as discussions between family members or a meeting of the Order. While it might not be Blade Runner and while the performances will occasionally have you thanking the humanoids for having blue skin so as to be able to distinguish between human and robot, as a camp, allegorical sci-fi vehicle it won’t disappoint.