How important is music to film? The American Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences would say important enough to merit an Oscar each year since 1935, not only for an original score, but an original song as well. Most prestigious film festivals give awards to composers and musicians thereby acknowledging their work as a creative and invaluable contribution to film.

In fact, many movies we love are to a large extent recognizable due to memorable original scores accompanying them. What would Psycho’s shower scene be without Hermann’s unnerving string section movement? Or would Darth Vader’s appearance in Star Wars be as terrifying without Williams’s dramatic score, including the intimidating Imperial March?

The field of film music is also susceptible to genre conventions, meaning that the music will prepare us in time for the kind of film we will be watching. Music commonly used in thrillers will not find its way to a light-hearted comedy and so on. All in order to ensure the viewer that his expectations will be met and that no surprises will occur.

Even art films that boast transcending genre boundaries in many cases tend to sound very similar to one another. But regardless of how well thought-out music use is, the truth is that near all of the directors will resort to some sort of melody accompanying their work.

It’s not just the original score, however. Quentin Tarantino, for instance, lovingly picks out songs he deems appropriate for each of his films, and has never hired a composer to create an original score, save for his latest film-in-making, a deviation from that rule, as he chose to enlist the help of his favorite Ennio Morricone in creating an apt western score.

The films of Martin Scorsese or Paul Thomas Anderson all tend to have a fair amount of pop music following the action on the screen. These soundtracks are later sold as separate works, not just in order to promote a film, but really for the pleasure of listeners who enjoy a good compilation. In such ways the music of a film lives on outside of it, in commuting cars, in edgy clothing shops, or at college dorm room parties.

To summarize, music contributes to film in many ways. Whether it’s an era-appropriate pop song in an 80s set film for the sake of authenticity, or a genuinely moving original piece, a soundtrack is commonplace. Why, then, would the creative choice behind a film include a deliberate absence of a musical score? Is it only thanks to music that films can pull on our heart strings? A number of authors would disagree and in turn display their convention-defying work.

Here is a collection of films characterized by a lack of soundtrack in the colloquial sense. That requires additional explanation. It doesn’t mean that the films from the list are completely devoid of music. In fact, some will allow us to hear a song or two, but only the music where a source is immediately identifiable on screen and heard by the characters themselves, i.e. diegetic music, primarily utilized as a means of emphasizing realism.

Aside from that, the entire duration of each of the films from this list is characterized by a complete lack of tunes. Examining each film individually will help us understand the reason behind such a choice.

15. Stray Dogs (郊遊, Tsai Ming-liang, 2013)

A man stands in the rain by a busy intersection holding an advertisement for real estate. Cars are passing by. Minutes pass. Cut. The film in its very long entirety (almost two an a half hours) is a composition of long, static and to a large extent uneventful takes which conceal a story within. Not that it is difficult to understand, but rather demanding to sit through.

We follow a man living in the streets with his two young children. At one point in their precarious lives they encounter a female groceries clerk who attempts to connect with the father. However, his reserve and restraint prevent any meaningful relationship, and just as it happened, it ends.

Some critics were right to call it a series of tableaux rather than a story. The shots are unrelated to one another and really resemble photographs more than anything else. This is especially true with wide shots which often include telling background details.

Being extremely low on dialogue, the film relies entirely on ambient sounds, which can make the process extremely painful for the viewer.

14. The Celebration (Festen/Thomas Vinterberg, 1998)

A prolific Danish author, Vinterberg is too often in the shadows of his compatriot Von Trier, who always manages to attract more attention from the media with his controversial films. The Celebration is Vinterberg’s second feature film and it garnered much praise from the critics with its scathing attack on bourgeois mentality, a target ever so popular in Europe. Aside from sharing the same homeland, Vinterberg and Von Trier are both behind a filmmakers manifesto called Dogme 95.

The idea behind the manifesto is to oblige signatories to adhere to certain rules, all of which boil down to baring the film down to its essentials: the story and the actors’ performances. Naturally, the rules were broken almost always to a small or large extent from the inception of the manifesto, even with The Celebration which comes very close to fulfilling Dogme 95 criteria.

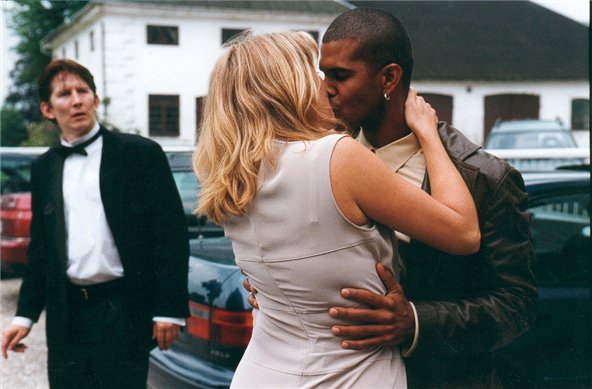

One rule that was not broken was the use of exclusively diegetic music, which in combination with a hand-held camera gives off a feeling of a home video. However, the rich family which is the focus of the film evokes anything but homesickness with the abundance of skeletons in the closet.

13. Ordinary People (Vladimir Perišić, 2009)

One of better examples of how the lack of music in a film can actually emphasize the actions on screen, this little indie Serbian war drama has the unfortunate fate to share its name with a much more famous film (family drama directed by Robert Redford in 1980), and therefore probably remain in its shadow despite the entirely different subject matter.

Minimalist in every sense, from plot to photography, from the number of acted roles to the number of spoken lines, Ordinary People may be difficult to sit through, but unlike Stray Dogs, it at least has a better sense of appropriate duration. Clocking just under 80 minutes, it ends before it gets too repetitive. However, provided the right amount of patience from the viewer exists, it can be a striking piece at times, showing us the banality of evil in Hannah Arendt’s sense of the term.

It follows a group of unnamed soldiers in an unnamed war (the idea being to represent all wars, or rather any war) who comply with the orders of executing civilians. They commit the atrocities not out of sadism, or ideological fundamentalism, but because the acts were justified by their superiors and the burden of responsibility lifted from them.

The inevitability of their deeds is amplified by the striking heat evoking the setting of Camus’ Stranger. With nothing but crickets in the background, mass murder is even more frightening.

12. Chop Shop (Ramin Bahrani, 2007)

After a brief white-on-black title card, we are thrown right in the middle of young Alejandro’s tough life on the streets, as we see him patiently waiting alongside a group of older day laborers by an expressway. The men jump simultaneously upon the sight of a prospective employer in a pick up truck. The would-be boss is addressing them in Spanish and English alternately, selecting those he deems can be useful, and leaving others.

Being only ten years old, Alejandro is rejected, but he sneaks in the back, demonstrating his determination to us, the viewers. However, this trick doesn’t work with the employer, who kicks the boy out as soon as he is discovered. Instead of any music usual for opening scenes in films, we only hear the chatter, people clamoring and traffic passing by. This style of docu-realism is consistently present throughout the film, the veracity of on-screen events emphasized by an oft-shaking camera.

The style common to Bahrani is similar to what the Dardennes brothers had been doing since 1996, but Bahrani is mostly interested in the American dream, and the question of what it means for the latest generation of immigrants. Alike the main characters in Man Push Cart (2005) and Goodbye Solo (2008), Alejandro already has an idea of what he wants in life and how to get it.

In a short while after the events from the beginning, Alejandro manages to find work and lodgings in a car repair shop, as well as a job for his older sister. The money they makes every day working for their new bosses will help them buy their own fast-food truck and find personal freedom. Unfortunately, the American dream has a tendency to turn into a nightmare.

This film makes a point of everyday struggles of the poor immigrants, and stresses that point with its bare raw imagery stripped of everything deemed unnecessary to the story. Aside the fact that the lack of a soundtrack contributes to the abovementioned docu-style, it testifies to the director’s desire of avoiding pathos.

In fact, the only music we hear is either reggaeton blasting from cars passing by the auto repair shops, or sentimental latino love songs in a fast food joint Alejandro and his sister sometimes treat themselves to. As much as Spanish is heard on the radio, it is heard on the streets.

11. The Defiant Ones (Stanley Kramer, 1958)

Even though the film opens with a song, we are immediately able to identify its source: Noah Cullen, a black convict sitting in the back of a prison van which is blindly advancing through a rainy night in the Deep South, transporting several others like him. As a method of precaution, they are bound to one another by chains.

Cullen, being the only black man in the group, has John Jackson – a white man (Tony Curtis) on the other side of the chains – a rare example of departure from usual segregation practices in the region. The two get into a fight on account of Cullen’s song, but at the same moment the van is forced off the road in an attempt to evade an incoming truck, and the ensuing crash liberates them in the process. Already disliking each other, they are forced to rely on each other in order to survive the hunt.

The concept has been copied in many films, but the maturity of the theme as explored here is noteworthy. Director Kramer later made racism a topic in two important films of his: Judgement at Nuremberg (1961) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), again with Poitier in the lead.

Some critics, however, focused on the lack of depth behind Poitier’s character, calling him a Magical Negro, assuming he’s only there as a narrative device that helps the white main character to overcome his prejudice. While that may be true to an extent, as Cullen’s experience does open Jackson’s eyes to the racial prejudice of his beloved south, and to the suffering of the blacks, it would be a mistake to call Cullen an undeveloped character.

Cullen’s ballad serves as a theme for the film and sets the mood, but the rest of the film plays out without any music. That is, except for the occasional and unexpected jazzy tunes played from a posse member’s radio.

10. The Homecoming (Peter Hall, 1973)

Directed by the same man who was behind its theatrical production of this play by Nobel prize-winning playwright Harlod Pinter, The Homecoming also features practically the entire cast that appeared on stage.

Those familiar with Pinter will instantly realize: the play is all about the words and even the pregnant pauses between them. The words cut through air with relentless vigor, and spew vitriol of unprecedented proportions. Words are like sharp deadly blades and no music dares appear to try and dull their edges.

The story deals with the titular homecoming of one philosophy professor, Teddy, and his wife Ruth, to his family’s North London flat. The rest of the family are all vicious masculine men who take turns at tormenting each other. A sense of claustrophobia stems from the fact that they are all confined to one same room. The characters lack humanity to such an extent that they incite nothing but contempt and disgust from the viewer.

Considered by many to be one of Pinter’s best works, it is at the same time a very cryptic piece, which makes it difficult to interpret on the top of being difficult to endure.

9. Two Days, One Night (Deux Jours, Une Nuit, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, 2014)

Anyone vaguely familiar with the work of the Dardenne brothers will have noticed that they refuse to resort to underlying musical scores in order to heighten the viewer’s emotion. In fact, the only film that deviates from this practice is The Kid With a Bike. Similar to their other works, Two Days One Night is in its essence a debate on morality in a world obsessed with self-preservation.

The story follows Sandra (Marion Cotillard), a young married mother of two, returning to work in a solar panel factory after a battle with depression. Unbeknownst to her, the management realized that her contribution is not necessary, and that she might lose the job if the other colleagues vote for it as well as a hefty bonus. With only a slight chance to turn the vote in her favor in just two days, Sandra must also overcome her weakness and her fears.

When faced with the question why they avoid using music in their films, they initially resist attributing it to an ideology, but soon enough admit that the sound and rhythm of bodies and objects that interact is the most important noise to them to be heard on film. This effect works perfectly in Two Days One Night and is akin to hearing a person’s inner workings, especially in scenes where Sandra is alone, looking for opportunities to talk to her co-workers and implore them to understand her position.