As much as mainstream Japanese filmmakers excel in family drama, “underground” films excel in exploitation. Since the end of the 60s, when the increased popularity of television had already taken a significant toll on the industry, most large-scale studios were forced to produce films that included sex, violence and S&M in order to earn a profit.

This began the rise of the exploitation genre, a category that, even nowadays, manages to shock people. The following list includes 10 of the most distinguished ones.

10. Lady Snowblood (Toshiya Fujita, 1973)

Quentin Tarantino turned the public’s attention toward this particular movie, when he used several of its themes and settings to shoot “Kill Bill”. “Lady Snowblood” is based on the homonymous manga by Kazuo Kamimura and Kazuo Koike. Dark Horse Comics also published a translated edition in the US in 2005.

Kitahma Okono and three men, Takemura Banzo, Shokei Tokuichi and Tsukamoto Gishiro, assault a family, killing the husband and the son and raping Sayo, the wife. They continue raping her for days after the incident until Shokei brings her to Tokyo with him as his concubine. During sex, Sayo wounds him fatally with a knife, so she ends up in prison.

Sayo has nothing except revenge on her mind, and she ends up having sex with every guard that comes her way in an attempt to conceive a powerful son, who will exact revenge in her stead. Eventually, one of them impregnates her; however, she delivers a girl and dies during childbirth. However, shortly before that, she forces her fellow inmates to promise they will tend to the infant. Moreover, she makes them swear an oath that she grows up to take revenge in her stead.

Six years later, one of them hands over the little girl to a monk, Dokai, who trains her in swordsmanship and martial arts. After she completes her training, Yuki renames herself to Lady Snowblood and sets on the path of revenge.

Toshiya Fujita directs this movie and particularly excels in one aspect: He lets Meiko Kaji, the protagonist, shine with her presence. Additionally, he does an excellent work of adapting the manga.

Kaji is thrilling as usual, chiefly due to the “cold” beauty of her face, though also through her acting. The latter incorporates a variety of feelings, exclusively through facial expressions and gestures, an ability so often utilized in Japanese cinema. Her usual role in the 70s, as the embodiment of revenge, finds its zenith in this movie.

9. Tokyo Gore Police (Yoshihiro Nishimura, 2008)

A remake of one of Yoshihiro Nishimura’s earlier works, “Anatomia Extinction”, “Tokyo Gore Police” is probably one of the sickest and definitely one of the foremost visually impressive films on this list.

In future Japan, a paranoid scientist named Key Man has unleashed a virus that infects truncate individuals, turning their missing parts into weapons. The police calls the individuals affected “Engineers” and consider them extremely dangerous, thus the creation of a special unit, the Engineer Hunters. Ruka, the protagonist, is a girl who occasionally lends a hand to the aforementioned team, while searching for her father.

The script is unquestionably simplistic; however, it could not be additionally complex, since Nishimura’s obvious purpose is to depict raw violence in all its forms. Accordingly, “Tokyo Gore Police” includes sadism, truncation, deformations, sick sex scenes and impressive battle scenes at the same time. Additionally, all the above are bathed in blood, as it is supposed to be with every splatter-exploitation movie.

Still, what sets this particular movie apart is its technical soundness. The character design is inspired, the set design is meticulous, and the special effects are impressive in one of the finest depictions of a sick imagination.

All of the above are largely due to Nishimura, who also has a hand in the majority of the movie’s technical aspects, including makeup, special effects and editing. Eihi Shiina, one of the foremost distinguished actresses of the genre, plays Ruka.

8. Gothic and Lolita Psycho (Go Ohara, 2010)

Another movie that benefits largely from Yoshihiro Nishimura’s presence, “Gothic and Lolita Psycho” is probably the foremost ridiculous title on this list.

In a transparent reference to “Kill Bill”, five peculiar individuals invade little Yuki’s home on her birthday, assassinate her mother and leave Jiro, her father, handicapped. A few years later, Yuki transforms into a gothic Lolita and initiates her revenge upon the five murderers, using an umbrella weapon her father manufactured. Additionally, along the way she realizes she has supernatural powers.

The director, Go Ohara, seems to grasp what a successful sample of the genre ought to entail: A female protagonist fighting cute girls, unstoppable action, anime-like aesthetics, some “peeking under-the-skirt” humor that manifests through hyperbole and huge amounts of blood.

Nishimura, as usual, produces an excellent result with the makeup and the special effects. Rina Akiyama, a former AV idol who was once named “Japan’s Greatest Butt”, plays Yuki. “Gothic and Lolita Psycho” also screened in festivals in Taiwan and Germany, and was released on DVD in the Netherlands and the US.

7. Ichi the Killer (Takashi Miike, 2001)

Takashi Miike, one of the masters of the genre, took the homonymous, hysterical manga by Hideo Yamamoto and created one of the foremost controversial films of all time.

The leader of a Yakuza family enigmatically disappears and his subordinates believe that he was murdered. Kakihara, his second in command miffs at the incident and is intent on extracting revenge. However, Kakihara is not your regular violent Yakuza.

On the contrary, he is a schizophrenic, sadomasochistic misanthrope, irrevocably in love with his boss, who enjoys inflicting as much as receiving pain. Accordingly, when he receives information that the perpetrator is the boss of a rival gang he proceeds on capturing and interrogating him, in his own, uniquely violent way.

Unfortunately, the culprit is not a gangster but a lonesome vigilante named Ichi, who works under the directions of a mysterious individual. The former hides quite a disturbed personality, underneath his normal, gentle face, a condition the latter exploits, making him murder people, without his actual consent. The situation takes a turn for the worse when he orders him to wipe out Kakihara’s gang.

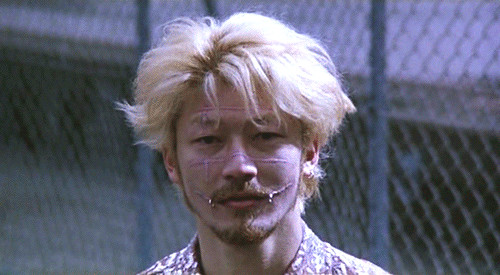

Miike portrays a collection of the foremost notorious characters ever appearing on film, all of which appear to relish pain and none of them is even remotely decent. Their visual depiction is accordingly extravagant, with Kakihara’s blond hair and motley garments and Ichi’s costume that entails a huge ace on his back (Ichi means one in Japanese).

Moreover, Miike includes a plethora of exceedingly violent scenes that even reflect on a sexual level and occasionally occur without any given reason. His message is quite clear: Every individual’s character includes a percentage of sadism and masochism. Ichi is a genuine ode to violence, thus this is the reason for its international cult status.

6. Visitor Q (Takashi Miike, 2001)

This straight-to-video release was part of a collection of six movies, the purpose of which was to explore the benefits of the low-cost digital video medium. Miike, of course, did not miss his chance to direct another exceedingly violent film.

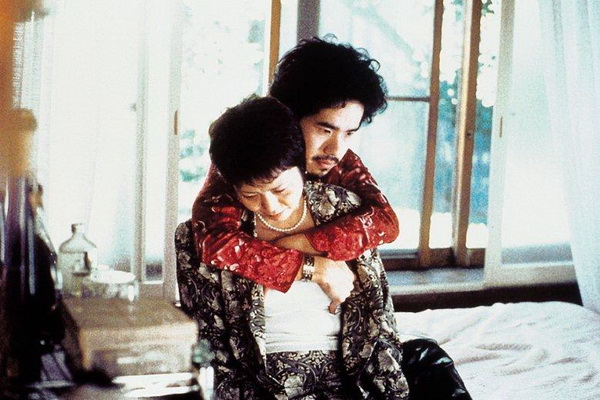

The script revolves around the Yamazakis, a family of four, all of who are quite disturbed individuals. Kiyoshi, the father, is a former reporter trying to shoot a documentary on violence and sex among youths. Therefore, he spends his time recording Takuya, his son, on camera, while his classmates bully him; he also occasionally has sex with his prostitute-daughter, Miki.

Takuya, frustrated by the constant bullying, takes out his fury on his mother, Keiko, beating her over any insignificant excuse, even in front of his indifferent father. Keiko finds solace in drugs when she is not prostituting herself. Eventually, an individual unknown to them establishes himself in their house, proceeding subsequently into torturing all of them. Through actions including incest, murder and necrophilia, chiefly caused by the stranger’s presence, the Yamazakis manage to become a family again.

Miike incorporates in “Visitor Q” the aesthetics of a reality show, thus resulting in a film that resembles an experiment of what would happen if he were to direct a sitcom.

He presents an inordinately problematic family, whose members still appear to function in an orderly fashion, where each one plays a role, without ever questioning the obvious pervasiveness of each other.

His characters portray the archetypes of the decaying contemporary Japanese society. Kiyoshi, who feels humiliated due to his labor failure, sexually ignores Keiko, who feels deprived. Takuya is a spoiled brat who receives and delivers violence and Miki has neither sense of purpose nor direction in her life.

His message is quite a pessimistic one: There is little hope for the modern family, whose only chance of maintaining the institution resides on the intervention of an external force.

In conclusion, “Visitor Q” is a grotesque study of the human psyche, by a filmmaker who has transformed the rape of our aesthetics into his means of expression.