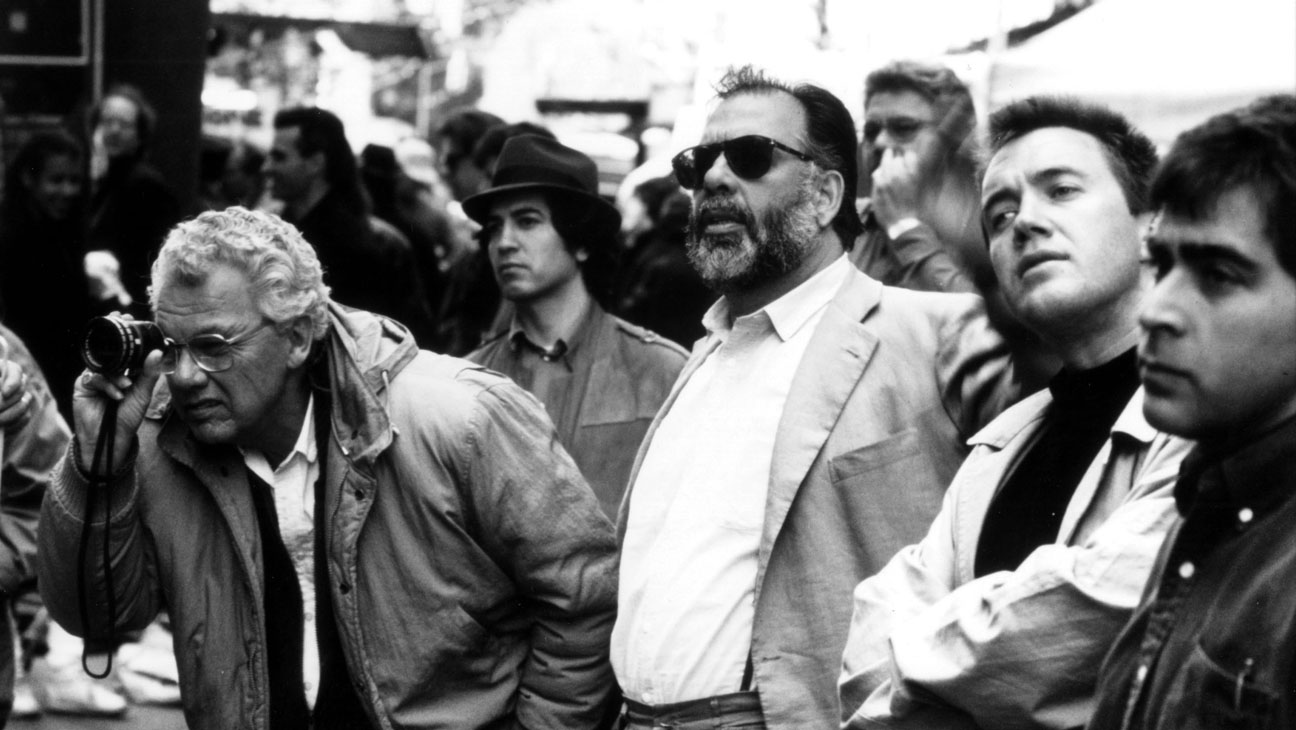

Gordon Willis has long been considered one of the greatest cinematographers ever to step behind a camera. It’s hard to imagine 1970’s cinema without his immeasurable contributions to the form, and through his fantastic collaborations with a variety of filmmakers (Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen and Alan Pakula worked with him numerous times) he put his distinct aesthetic stamp on every project that landed on his resume.

Other notable filmmakers that he worked with included Hal Ashby, Herbert Ross, James Bridges, Dubbed “The Prince of Darkness” by friend and colleague Conrad Hall, due to his fondness for low-light photography with an emphasis on shadows and various shades of black, Willis was an artist who found beauty in the harshness of the photographic image, with his films continually pushing what was known and previously acceptable in terms of their smoky and burnished qualities.

Despite shamefully never being bestowed with an Oscar for Best Cinematography, the Academy awarded him an Honorary Oscar in 2009 for his career in general; he was nominated for his work on The Godfather Part III and Zelig but lost on both occasions. His work was ahead of its time, and due to his lack of love for the Hollywood machine, many feel he had been slighted by his peers and contemporaries during his illustrious career, but for any film lover, there can and will be only one Gordon Willis.

Here’s a sampling of 10 of his most distinctive films that bear his name as Director of Photography.

1. The Godfather

The Godfather is one of the great American films for many reasons, but one of the clear-cut strengths that this film has rests in Willis’ groundbreaking and heavily influential use of low light photography, a favoring of sepia and golden tones to accentuate the time period, underexposed film stock which resulted in a darker, firmer image, with all of those tricks becoming commonplace in modern moviemaking.

The Godfather boasts all of the tremendous performances that give the film so much emotional heft, and of course, Coppola’s studied direction is a master class in storytelling. But when it comes to the aesthetics of the film, it’s important to note that there’s nothing in The Godfather that feels inorganic or superfluous; the style is always complimenting the story, arguably strengthening the morally ambiguous themes of the story, thus helping to provide more depth and understanding to the images themselves.

Look no further than the scenes that showcase Marlon Brando, who Willis frequently captured in shadow, blacking out his eyes to suggest the inherent struggle and deep sadness from within him as a man. And with the film juggling locations (New York, Los Angeles, Sicily), the cinematography never felt disjointed, with Willis maintaining a strong sense of overall artistic cohesion that suggests a true artist’s touch. There was hardly anything show-offy about Willis’ work on The Godfather, and it might stand as one of the most subtly gorgeous movies ever created.

2. The Godfather Part II

Arguably the greatest sequel of all time, and the only follow up to win Best Picture at the Oscars, The Godfather Part II is one of those seminal films that people keep coming back to over the years, and with great reason: It’s a masterpiece of filmmaking and storytelling.

In conjunction with Francis Ford Coppola’s stirring and sweeping direction, Willis expanded upon the first film’s dark and smoky visual style, which helped to create a sense of uniformity between the two films; his underrated work in Part III would cement the entire trilogy.

A sense of fatality permeates much of the narrative of The Godfather Part II, with the huge cast of characters all doing heavy dramatic lifting, with Willis the steady hand behind the camera, enveloping everyone in a morally shrouded cloak of atmospherics and chiaroscuro visual aesthetics.

The now famous bronze and amber-hued color scheme that could be found in the first two films created a sense of family in terms of bridging the first two chapters together, while The Godfather Part II, on its own, becomes an even more epic and ambitious piece of storytelling than its highly regarded predecessor, showcasing both the past and the present within its expansive narrative, all brought to life by Willis’s studied and painterly camerawork.

3. Manhattan

One of the silkiest black and white films ever committed to celluloid, the widescreen cinematography by Willis on Allen’s Manhattan is some of the most impressive and shimmery work that the master craftsman ever produced. This is one of Allen’s most romantic films (albeit bittersweet), as the script that he co-wrote with Marshall Brickman covered the usual neurotic behaviors that came to dominate his oeuvre.

Directed with a sense of grace by Allen, the film became an immediate classic, and via the dreamy photography that casts New York City as its own special character, Manhattan possesses a formidable sense of style that feels incredibly particular and studied.

The unforgettable image of Allen and Diane Keaton sitting near the 59th Street Bridge is one of those iconic moments in film history, with Willis demonstrating an innate understanding of how to frame his actors within the anamorphic 2.35:1 compositional space, and how he favored spatial geography as a way of representing space and comfort for the characters within the emotionally fragile narrative.

It’s interesting to note that Allen demanded that all home video copies of this film be released in letterboxed format only, thus preserving the original aspect ratio.

4. All the President’s Men

All the President’s Men is the best journalism thriller ever made, and a large part of the film’s success is due to the carefully measured and totally naturalistic cinematography by Willis. Whether it be the interior of a newsroom or a shadowy parking garage, Willis used only what was necessary, and through smart choices in framing and patient use of shot selection, the film never became unnecessarily stylized.

There’s incredibly clarity to the images in this films, not necessarily from a lighting POV (this is the Prince of Darkness, after all!), but rather, there’s a truthfulness to the visual style, as if Willis and director Alan Pakula were daring the audience not to believe what it was that they were seeing unfold before their eyes.

Both Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman were electric in this film, and the way that Willis captured both of them, as Men of Action while on the job, has served as a precedent for many filmmakers throughout the years.

The shots of the camera gliding through the newsroom with the bright, overhead lights blaring down created a wonderful sense of verisimilitude, and the way that Willis and Pakula used camera placement and shot length (in tandem with the great editor Robert L. Wolfe) to dictate suspense and tension is still a model for today’s current filmmakers.

5. The Parallax View

Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View is one of the most unnerving and unique paranoid thrillers from the 70’s, taking its ambitious and chillingly layered narrative concoctions and making them just believable enough. It’s one of those films that offers new details to be discovered upon each viewing, and it’s clear that the film served as a major inspiration for future efforts like Peter Hyams’ The Star Chamber, David Fincher’s The Game, and Rob Bowman’s The X-Files: Fight the Future, to name only three.

It seems insane to think that this film hasn’t been given the unnecessary remake that Hollywood seems to love to throw out, but hopefully, people are smart enough to leave this one alone. Sure, some savvy filmmakers could craft a solid updating, but there’s something so incredibly 70’s about this film, from Warren Beatty’s look and attitude, to the cryptic plotting, to the downbeat finale.

But most of all, Willis shot the ever living hell out of this film, favoring bold widescreen compositions, startling scene transitions and starting-points, with the final section becoming almost surreal and certainly nightmarish due to the use of subjective and then objective camerawork.

The diabolical screenplay by David Giler and Lorenzo Semple Jr. (with uncredited rewrites by Robert Towne) never let anyone off the hook, and the beyond creepy musical score by Michael Small immediately set a nervous, anxious tone that Pakula maintained for the entire duration.

Effective supporting performances by Hume Cronyn, William Daniels, Paula Prentiss, Earl Hindman, William Joyce, Walter McGinn and Kelly Thorsden are on display, while Beatty anchors the film with class and the perfect amount of cockiness and uncertainty. And then there’s the ruthless finale, which feels both earned and inevitable, with the closing moments ranking as some of the iciest in cinema history.