We always tend to think of film as a director’s medium, and while that’s largely true, there’s another force that can fundamentally shape a the direction a movie takes too: the writer. This much-maligned presence doesn’t always get the credit they deserve, but although a great director will shape a screenplay as they see fit, a great writer lays a template. Or to put it another way, a great screenplay is a movie that demands to be made.

Although there are no entries on this list from 2015, this year in film has produced plenty of great writing in and of itself. Let’s also not forget that Charlie Kaufman’s Anomalisa has yet to come out, and would be all but guaranteed a spot. Nevertheless, discounting 2015 for now, here are the best screenplays of the decade so far.

1. The Social Network – Aaron Sorkin

Prior to 2010, nobody associated Aaron Sorkin with cinematic visuals. Mr. Sorkin himself has said that he writes, “people talking in rooms.” But when David Fincher got his hands on The Social Network, it became clear that Sorkin’s writing could be more than just a conduit for a snappy dialog, that his unique rhythms and tempos could also create one of the most dynamic, propulsive, and yes, visually stunning films of the decade.

In Fincher’s hands, The Social Network transcended the idea of “people talking in rooms.” But while Fincher may be responsible for the end product, Sorkin’s Oscar-winning screenplay is a titanic feat on its own. There is so much pathos, and humor, and drama in this story, it plays as much like a Greek tragedy as it does a modern story of a tech billionaire.

And although people still speculate about how much of it is accurate, the film also ushered in a new, more interesting era of biopics, where the factual truth became less important than telling a good story. Say what you want with this new, devil-may-care approach, but one thing you can’t deny post-Social Network is that the movies themselves have gotten better.

Before The Social Network went into production, many wondered what a painstaking and expert craftsman like Fincher could possibly see in the work of the boundlessly talky Sorkin. The movie’s style alone proves this, but it’s also worth remembering the cynical worldview of Fincher’s other movies. Sorkin is an optimist at heart, but what makes The Social Network standout in his catalog, what makes it special in his larger oeuvre, is that it is deeply, deeply cynical.

With this year’s Steve Jobs (which Fincher was also slated to direct for a time,) Sorkin returned to the same well of the tech world for this take on another billionaire/egomaniac/genius. But given audience’s less than enthusiastic response to the film, it’s hard not to wonder if its uplifting, borderline sappy ending was a mistake in the otherwise fascinating story of such a complicated man.

Meanwhile, one of the reasons why The Social Network is still the best screenplay of the decade is that it proves that sometimes, even great optimists have to go dark.

2. Her – Spike Jonze

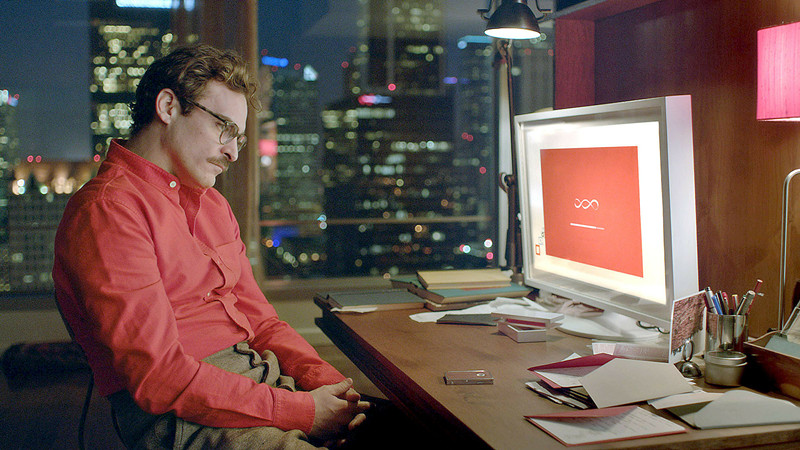

“A romance between a man and his phone? That’s ridiculous. Who’s going to take that seriously?”

It would be hard to fault someone if this was their reaction upon hearing the premise for Spike Jonze’s 2013 work of genius. Because although Her is, in some ways, a comedy, it’s not the absurdist, satirical take on technology it could’ve been. Instead, it’s a melancholic romantic comedy about searching for connection and navigating the perils of a new and different relationship.

The movie alternates between being laugh out loud funny and devastatingly heartbreaking without one beat feeling out of place. And when, in its final act, it dares us to question the nature of humanity itself, we are left with a sense of knowing a little more about life than we did when we entered the theater.

That’s a lot to pull off in a movie about a guy falling in love with his phone, but thanks to its Oscar-winning screenplay, Her nails it. What makes Jonze’s writing, perhaps even more than his direction so impressive in this movie is his expert characterization. The final cut is a dizzying mix of futuristic fashion and magnificent bursts of color.

But before any of that was possible, Jonze had to make the relationship of loner Theordore (Joaquin Phoenix) and O.S. Samantha (Scarlett Johansson) sing on the page. And boy does he ever. Samantha is so perfectly nuanced and wonderfully realized, Jonze’s writing allowed Johansson to give one of her best performances ever, without even appearing onscreen.

But the screenplay is also impressive for what it says about technology. This is a story where the future has not been destroyed, or drastically improved by tech, and while other filmmakers rush to predict destruction, Jonze wisely leaves judgment off the page.

Funny, all those years we talked about the writer of Being John Malkovich and Adaptation., it turns out the guy who directed those movies had a way with words too.

3. Before Midnight – Richard Linklater, Julie Delpy, and Ethan Hawke

Before Midnight sings with the rich hum of familiarity. After two other films in two other decades, Richard Linklater, Julie Delpy, and Ethan Hawke clearly know the characters of the Before trilogy like the back of their respective hands. Linklater gets trashed a lot for not having a more distinct visual palette, but with settings this sumptuous, characters this original, and dialog this vibrant, he hardly needs to move the camera at all to create his desired effect.

That effect being, of course, the passage of time. Although Linklater’s 2014 masterpiece Boyhood will probably stand as his ultimate meditation on this theme (which he returns to again and again,) the Before trilogy will always retain its significance, for the way it shows how relationships grow an change, for better and for worse.

The fact that star-crossed lovers Celine and Jesse spend more time fighting in this film than in the other two is significant, and sometimes painful to watch, but it’s also what makes this the best film in the trilogy. The three writers here don’t pull punches about just how hard fighting for love can be. Yet in the end, they also suggest that the fight is worth it, and that while history and shared experience cannot save a relationship alone, the willingness to try again, to keep going, maybe can.

4. Bridesmaids – Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo

Let’s get the whole “women in comedy” thing out of the way right now. Yes, Bridesmaids is significant in its depiction of funny women. No, not enough movies have come out like it sense. But the reason Bridesmaids is one of the best screenplays of the decade has nothing to do with gender. Bridesmaids is one of the best screenplays of the decade because it’s also the decade’s funniest movie.

Kristen Wiig and Annie Mumolo’s Oscar-nominated script is a roadmap for everything good comedies should do. The jokes are hilarious, the characters are unique, the set pieces are well-paced and well-structured within the larger narrative, and there is enough genuine emotion behind everything that is going on to make you care what happens at the end of the movie.

Plenty of comedies are smart and funny without much feeling. But Bridesmaids succeeds because it knows that even when characters are freaking out on planes and shitting themselves in sinks, you have to have compassion for them in the midst of their misfortune.

5. Lincoln – Tony Kushner

Here’s a tough task: make Abraham Lincoln vulnerable. Not brilliant, or commanding, or virtuous, but vulnerable. This is exactly what Tony Kushner did in his screenplay for Lincoln, Steven Speilberg’s 2012 film about our 16th president, which manages to do the unthinkable—make him a real person.

It’s said that Lincoln was actually a lot more soft-spoken than he’s often portrayed onscreen, and one wonders whether Liam Neeson, who was Spielberg’s first choice for the role, would’ve brought the same quiet subtlety as Daniel Day-Lewis did.

However, Day-Lewis was in a lot better position to play the great orator from the very beginning, thanks to Kushner’s script. Though a playwright at heart, Kushner succeeds in Lincoln by focusing less on big speeches and more on moments of uncertainty and restraint.

Kushner also manages to pull a bit of Schoolhouse Rock magic, making the “how a bill becomes a law” type of wheeling and dealing that went into passing the 13th amendment not only educational, but fascinating.