Stanley Kubrick is one of the most celebrated directors in cinematic history. His demand for perfection on screen, his incessant amount of retakes, and his incredible intelligence helped create some of the best films ever made.

More than that, though, since his death in 1999, his films have only grown in popularity. Looking at his entire canon, it’s easy to see some very distinct traits in his work.

1. One point perspective

There is an excellent video on Vimeo that illustrates Kubrick’s usage of one point perspective. Put simply for the layman, one-point perspective is an image that has only one vanishing point. It is most noticeable in images that involve long roads, buildings, hallways, and tunnels.

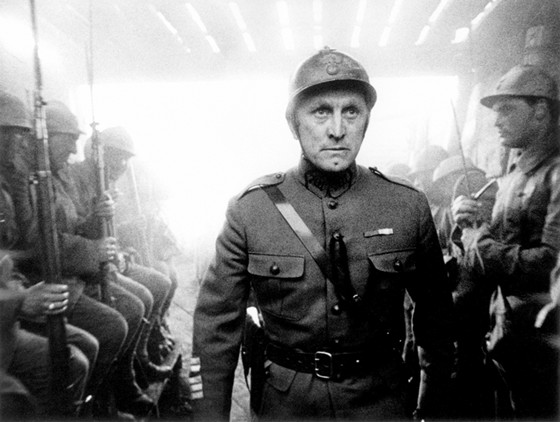

One point perspective is all over Kubrick’s filmography. It’s in The Shining, 2001, A Clockwork Orange, Full Metal Jacket, Barry Lyndon, Eyes Wide Shut, and Paths of Glory.

The shot composition is not only incredibly versatile in terms of atmosphere (it was used to show the famous “come play with us, Danny” hallway scene in The Shining, the jogging scene in 2001, and Alex slurping spaghetti in A Clockwork Orange) but it is also interesting to look at. Since there is only one vanishing point, there’s a lot to take in as a viewer.

Take the aforementioned hallway scene from The Shining: not only do we get the incredibly cramped width of the hallway, we also see the bloodied girls, the axe, the overturned chair, the painting that is slightly tilted, and the lone window. If that scene had been shot with close-ups, the viewer would have been unable to take in the true wreckage of the murder.

In this way, one-point perspective is one of the most important aspects of Kubrick’s films. He went out of his way to use this type of shot constantly, and because of this a viewer now associates that type of image with Kubrick.

2. Complicated tracking shots

Most of Kubrick’s films involve some complicated tracking shots. As soldiers run alongside tanks, rubble, burning buildings, and destroyed cars in Full Metal Jacket, the camera follows behind them for a minute and twenty seconds without cutting.

In the beginning of the same film there is the more famous example with Hartman yelling at the soldiers in a one minute and fourteen second long tracking shot.

In The Shining, the camera follows many characters, especially Danny as he rides around in his tricycle. In Eyes Wide Shut, the camera follows Dr. Hartford as he walks the cold streets of New York City. In 2001, the camera follows the protagonist as he jogs around the spaceship.

Again, this trait is in most of Kubrick’s films. It lends a certain amount of realism to the image. Since human beings’ eyes don’t “cut” (we are living life in one constant shot, if necessary to put it in such terms) a long tracking shot is the closest thing to “real” a film can present. It breaks down the barrier between film and viewer and adds an interesting dimension to the viewing experience.

3. Similar themes

Kubrick only chose films and themes that he wanted to make. It’s no surprise, then, that he often chose similar topics and themes throughout his filmography.

He’s explored war a number of times (Paths of Glory, Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove, Full Metal Jacket), human connection/love/interaction – generally lumping these things is frowned upon, but Kubrick didn’t make “love” films, or films about love, he made “human” films – (Lolita, Eyes Wide Shut, Barry Lyndon), human nature (A Clockwork Orange, Eyes Wide Shut, 2001) and further.

Kubrick was obsessed with people, above all else, and so it’s not surprising that all of his films are centered on the characters in them.

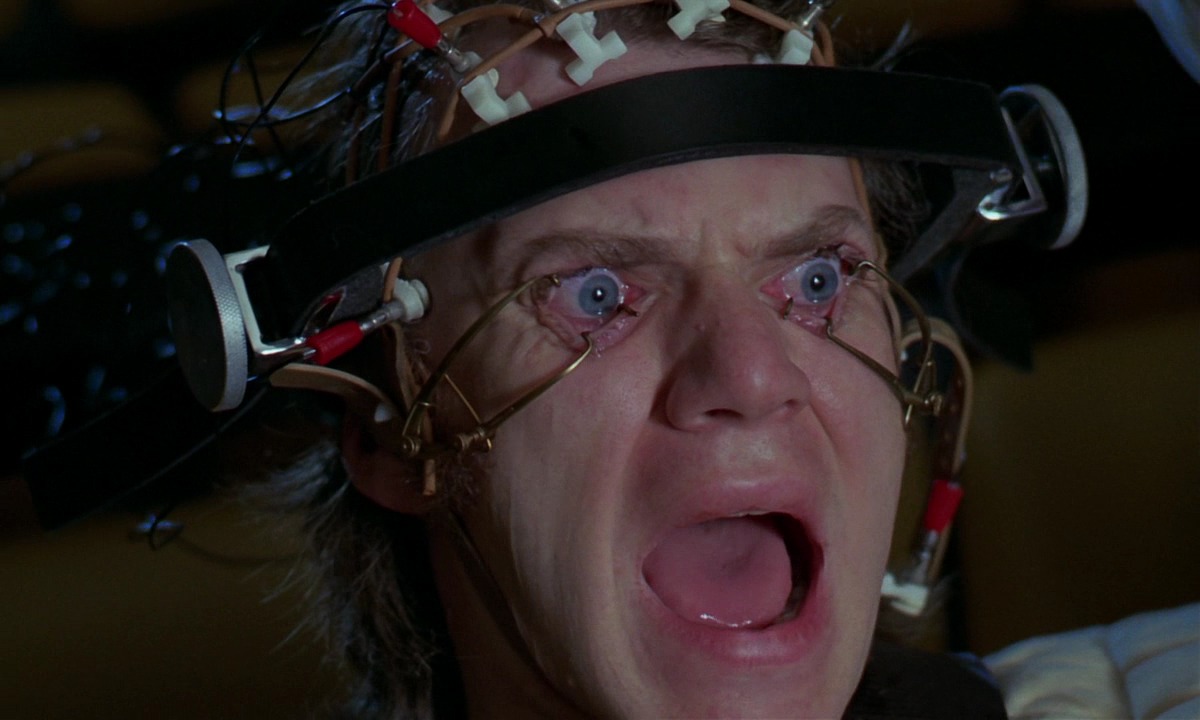

A Clockwork Orange is about many things, but it is mostly about human action, violence, and impulse. 2001 is all about human evolution, especially in contrast with other life forms and the machines humans have made. Lolita is about human perversions and interests.

Society often plays a role in Kubrick’s films as well. It’s visible more as a growth of the previous notion of human interaction. Society is, after all, a group of individuals that generally share a collective idea of morality, beliefs, and ideas (though this is certainly not a universal, or completely accepted, concept).

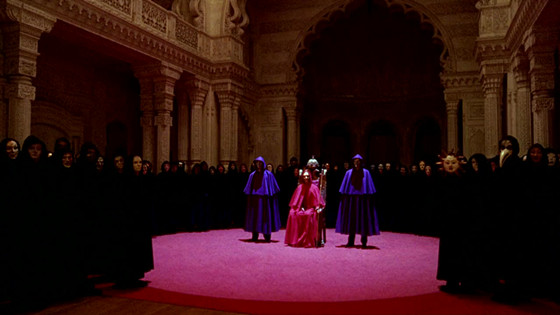

Emile Durkheim coined the term “collective consciousness” to illustrate this concept. In Eyes Wide Shut, society is very much in focus (both the “secret society” wherein the ritual takes place, and the surrounding people in society as Dr. Hartford walks the streets of New York City).

4. Subtlety in the presentation of his narratives

Speaking of Eyes Wide Shut, there is no more perfect example than it to illustrate Kubrick’s subtlety and usage of symbolism when presenting his narratives.

The ritual scene is perhaps one of the most jarring, confusing, and symbolic scenes Kubrick ever filmed. Between the masks everyone wears, to the increasingly odd presentation of sexual liberation and/or entrapment, Kubrick never overtly explains what is actually happening in that scene, or what that scene is supposed to mean it the context of his film.

Kubrick challenged his audience to think, to dissect film, and to be as much of a storyteller as he was. The ending of The Shining still perplexes some because of its seemingly incongruent nature in the context of the film. But there is an answer as to why it’s there.

The ending of 2001 (or even the entirety of it) takes a lot of time and thought to decipher. But there is a reason it’s there. If there’s one thing Kubrick wasn’t, it’s shallow. The man was a perfectionist, and if something was in his frame, it was meant to be there.

Kubrick could have held his audiences’ hands, walking them to the end of the film, while pointing out the imagery and symbolism and also entertaining them. But he didn’t, and that’s part of the reason why he’s as prolific as he is, even almost 20 years after his death. His films are like large steaks – you need time to chew the meat and savor the flavor before you swallow.

5. Focus on music/image relationship

Kubrick loved to toy with the relationship between music and image. Long before Tarantino and Scorsese made their way into the film industry using popular music to bolster their imagery, Kubrick was using Strauss to add dimension and intrigue to the opening of 2001, and Beethoven to add depth to Alex in A Clockwork Orange.

Tony Palmer, director of “Stanley Kubrick: Life in Pictures” explained it best when he said: “Before Stanley Kubrick, music tended to be used in film as either decorative or as heightening emotions. After Stanley Kubrick, because of his use of classical music in particular, it became absolutely an essential part of the narrative, intellectual drive, of the film.”

In this respect, Kubrick understood the usage of compositions for film in a way many others didn’t at the time. He understood that music was a natural sibling of the image, and one didn’t need to be subservient to the other.

Music can create similar feelings, and express similar themes and ideas, as visuals can. Kubrick essentially leveled the playing field, and in doing so created an entirely new approach to the craft of filmmaking.