Unlike the wide open vistas of the United States, the European road trip has always been constrained by borders and hampered by a chequered 20th century history that made traversing the continent a difficult proposition for a large part of it.

With that in mind, the European road movie often provides a very different proposition to the wanderlust of America, where the windscreen is your cinema screen. The road soon ends on the often dreary carriageways and service stations about as romantic as a flaccid two day old £5 cheese sandwich.

French theorist Jean Baudrillard captured the dichotomies of the European and American road well in his celebrated study ‘America’ in which he stated “Unlike our European motorways, which are unique, directional axes, and are therefore still places of expulsion… the freeway system is a place of integration… There is something of the freedom of movement that you have in the desert here, and indeed Los Angeles… the freeways do not de-nature the city or the landscape; they simply pass through it and unravel it without altering the desert character of this particular metropolis. And they are ideally suited to the only truly profound pleasure, that of keeping on the move.”

This is all not necessarily to the detriment of the European road movie however. Where in place of adventure and exhilaration, instead we have been provided with some of the greatest character studies from some of Europe’s greatest director – reeling off like a dream Criterion playlist – Bergman, Antonioni, Wenders, Godard, Bava, Kaurismäki et al.

From bickering couples to warring generations, from gangster flicks on the road to World War II adventures. The European road movie is a template on which filmmakers have gone wild. Here are twenty stunning examples to get you underway.

1. The Open Road – UK – Claude Friese-Greene – 1926

Advertised as “a cinematic postcard of Britain in the 1920s” – ‘The Open Road’ is a fascinating and touching time capsule of a lost world.

Claude Friese-Greene followed in the footsteps of his father, pioneering an early colour film process initially known as Biocolour, but would go on to be called ‘Friese-Greene Natural Colour’.

Friese-Greene initially sought to promote the process with short travelogues such as 1920’s ‘Across England in an Aeroplane’ (actually only covering Cornwall and Devon) before embarking upon an epic quest to traverse the entirety of Great Britain in an early Vauxhall D-Type.

During these interwar/pre-depression golden years, the rise of the motorcar had seen the concept of the road trip become the height of fashion, both in Europe and America.

Though at this time, the car was still largely the preserve of rich, despite playing field levellers such as Ford’s Model T. Therefore the opportunity for the cinema going proletariat to see far flung areas of the country was unprecedented – with the original presentation being in a series of 26 short travelogues shot between 1924 and 1926.

Now some 90 years later and collected into a single feature – ‘The Open Road’ is an important curio – if not a national treasure on a par with the pioneering cinematic experiments of Mitchell and Kenyon.

We see footage of the Thames – still as the industrious beating heart of the British Empire, Blackpool as the North’s premier holiday location in its halcyon years and the beautiful climbs of the Scottish Highlands barely touched by the tourism that the promulgation of the motorcar would shortly bring.

2. Le salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear) – France – Henri-Georges Clouzot – 1953

Now rightfully acknowledged as one of the great directors of mid 20th century French cinema, Clouzot actually had a rough ride of it from critics during his directorial career, derided as part of the generation of the Cinema du Papa by the Nouvelle Vague brats, the best write-ups he usually received were only willing to acknowledge him as a ersatz “French Hitchcock” rather than a fantastic suspense director in his own right. Did Hitchcock ever direct a 2 and a half hour rollicking nightmare trucker death trip however? (No)

The Wages of Fear is an adaptation of a novel by Georges Arnaud about a hard-scrabble bunch of mercenary truck drivers taking on a suicidal driving job. The first hour shows us the grim world in which our four drivers have become trapped, the nonspecific Central American location (in reality the south of France) dripping with an insufferable pestilent humidity and boredom.

A job is offered to drive four less than primo condition trucks filled with jerrycans of nitroglycerine 300 miles to extinguish some oil field fires. The job is offered by the ‘Southern Oil Company’ an enterprise broadly painted to symbolise the worst of American imperialist bloodsucking. This would lead to controversy upon the film’s original American release which would see over 20 minutes of such scenes excised from the cut shown there.

We aren’t expected to particularly sympathise with our four protagonists, they live in a world where they get by on a weary, contemptuous machismo and appear to all intents to be the agents of their own misfortunes. Regardless, the sheer intensity of the film’s second half, in which any significant bump in the road could see nothing remaining of the men but the fillings in their teeth, is pure relentless driving intensity.

Backed up by black as tar humour, this bleak jagged picture would receive a fine remake in 1977 as William Friedkin’s ‘Sorcerer’.

3. Smultronstället (Wild Strawberries) – Sweden – Ingmar Bergman – 1957

‘Wild Strawberries’ is an early picture from the period in which Ingmar Bergman would cement his reputation as the world’s premier auteur of life’s complexities. His obsession with death came to the fore with his previous picture, the art-house exemplar ‘The Seventh Seal’ (a road movie of sorts in itself), and continued with this, in which the tortuous oxymora of life are contemplated – youth and aging, love and hate, passion and reason, life and death.

The film follows Dr. Isak Borg (the legendary actor/director of early Swedish cinema Victor Sjöström) as he travels from Stockholm to Lund to receive an honorary degree to celebrate his 50 years as a doctor. An honour, yet an unsettling reminder of his twilight year’s fast approaching curtain time.

Bergman’s self-confessed terror of mortality is broached as Borg’s journey sees him reflect on a life he sees as full of mistakes and regrets. Some of these reflections being flashback sequences that were quite audacious at the time and are rightly celebrated.

As ever with Bergman, the underlying subject matter is as weighty as it comes, yet he shows a lightness of touch and humanism here that is rarely in evidence in a body of work defined by its emotional austerity.

4. Il sorpasso – Italy – Dino Risi – 1962

Released bang in the middle of an unbelievable period of creativity in the Italian cinema that spanned the late 1940s through to the early 1980s. With ‘Il sorpasso’ Dino Risi took the tenets of the popular Commedia all’Italiana genre which was famed for its satirical stabs at Italian society and applied it to a spiky road movie buddy template.

We meet Roberto (a fresh faced Jean-Louis Trintignant), a law student obsessively studying for his degree at the cost of all sociality. His staid studious life is suddenly upended when whirlwind of nature Bruno (commedia all’Italiana legend Vittorio Gassman) comes pilling into his life and forces Roberto into a hasty coastal road trip in Bruno’s battered Lancia convertible.

This proto-bromance shows a new youthful baby boomer generation of Italians breaking free of the austere neo-realist world of their parents. Risi though tempers the freewheeling atmosphere, casting an often scornful eye over our pair, particularly Bruno and his supposedly consequence free manic lifestyle and equally manic driving style (Il Sorpasso translating as ‘the overtaking’ a manoeuvre practiced constantly and often dangerously by Bruno throughout).

5. Two for the Road – UK – Stanley Donen – 1967

Stanley Donen, famed for his series of Broadway goes to Hollywood spectacles such as ‘On the Town’, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ and ‘Seven Brides for Seven Brothers’, would decamp briefly in Europe in the late 60s to direct this bittersweet tale depicting five stages of the marriage between Joanna (Audrey Hepburn) and Mark (Albert Finney).

Donen appears to have taken a European influence to heart as his willingness to play with cinematic form was unlike anything you would see from other Hollywood directors of the time. The marriage is presented to us as a series of fragments mashed up like loose jigsaw pieces.

The five segments are presented as five different road trips through the south of France on which the couple embark – from the ‘meet cute’ of their initial coming together, through the gradual disintegration of their marriage resulting in a fifth trip that echoes Rossellini’s earlier marriage on the rocks European road trip ‘Voyage to Italy’.

At the outset the narrative is chaotic as we rapidly move forwards and backwards again through time. This initial cluttered jumble though gradually begins to come together and through judicious editing, proves to be more than just a cinematic gimmick. The film presents a convincing portrayal of the passage of time, of initial niggles and irritations in the marriage gradually coming to the fore as destructive forces.

Hepburn and Finney struggle slightly to convince as the youngest version of themselves and Donen does betray his Hollywood background with an ending too conveniently jaunty and jovial – but overall the film provides a very entertaining portrait of a comically chaotic marriage.

6. Week-end – France – Jean-Luc Godard – 1967

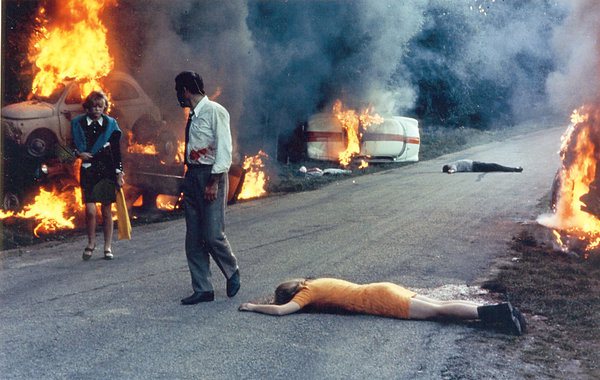

The Nouvelle Vague’s enfant terrible Godard had dipped a toe into road movie waters two years previously with the manic couple on the lam caper ‘Pierrot le Fou’. He then brought his period of relatively straightforward narrative cinema to a fireball conclusion in this bourgeois baiting vision of France in the midst of surrealistic guerrilla warfare.

The impressionistic French countryside having the touch paper lit from underneath it with a series of loosely tied segments presenting proto-Ballardrian car pile-ups and mangled victims.

As is often the case with Godard, the film is pretty much a 50/50 balance of impudent brilliance and utter boredom. You can be left drifting away from the film for long periods only to be drawn straight back in by a moment gobsmacking in its audaciousness. With the most notorious of these being a lengthy traffic jam tracking shot – all rage, chaos and ear splitting diegetic noise.

A film worth catching if only to capture a sense of the mood of the times, with the increasingly extremist polemic from the French left building towards the riotous events of May ’68 that would follow less than a year later.