Cinema is truly a unique medium. In addition to being an art form, it’s also a product that requires money and other resources to be made. Nowhere is it illustrated so well as in the strange phenomenon of “one-picture directors”.

A live-action feature usually costs in seven figures or more, and unless you’re Ed Wood-takes time, effort, and the strain of one’s creative resources to be made well. That may account for the fact that many entries on this list were directed by well-known actors. They have, doubtlessly, tasted complete creative control-and learned that with great power comes great responsibility.

Some of the entries were made by the erstwhile directors of animation and documentaries-who also, probably, came to conclusion that the bright lights of feature fame are not for them. Some directors here were done in by bad reviews or just plain public indifference, while others were suppressed politically or never given another chance due to disappointing box office.

The criteria for this list is strict-a film that is the given director’s solo live-action feature credit. My definition of “feature” is somewhere between those of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and SAG.

All films on this list, with one possible exception, run for 60 minutes or over. While one can argue that Tony Kaye (“American History X”) or Tobe Hooper (“The Texas Chainsaw Massacre”) are one-picture directors, they in fact have more than one feature in their filmographies.

The few recent entries here are by directors who have clearly moved on and back to their respective fields and are highly unlikely to grace the director’s chair again. Be prepared to be surprised.

24. Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are Dead (1990). Dir. by Tom Stoppard

Placed at the bottom of this list for a simple reason-it’s not a great film. Surprising, considering how many quality elements it contains. Altogether, however, they haven’t gelled to form a superior whole.

Sir Tom Stoppard has definitely earned his knightly spurs-he is one of all-time great playwrights. His relationship with cinema, too, has been very rewarding-he penned the scripts for quality films like Russia House and Empire of the Sun, co-wrote the cult classic Brazil, salvaged Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and deservingly took home the Oscar for Shakespeare in Love.

When it came to directing his masterpiece play that made him an overnight sensation, he opted to do it himself, with decidedly mixed results.

The play, which premiered in 1966, follows the titular characters, minor ones in Hamlet, as they struggle to place themselves in the world, to the point of being not sure of who they are. It’s frequently interrupted by actual scenes from Hamlet, as well as by shenanigans of the travelling players.

Brimming with humor and thought, it questions the nature of theatre itself, among other things. These qualities are largely missing from the film, making it, while entertaining, rather predictable. Although it did win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, at nearly two hours it loses a lot steam several times. That despite the facts that both hapless titular characters are very well played by such quality actors as Gary Oldman and Tim Roth, respectively.

Inspired, too, is the part of the Player King, played with a wink and panache by Richard Dreyfuss. Eagle-eyed viewers will also spot Iain Glen (from Game of Thrones) as Hamlet, in one of his earliest roles. Ultimately, though, it failed to live up to the success of the play. Every humorous, Stoppard claimed that he chose to direct it himself because “It just seemed that I’d be the only person who could treat the play with the necessary disrespect.”

If wondering whether to check this one out-see a theatrical production of a play. If it’s not being produced anywhere near you-read it first. A much more rewarding experience. Spoiler alert: both leads, Oldman and Roth, will be featured in this list.

Side note: Stoppard really proved that playwriting is his main forte, the amount of novels he has written also equals exactly one.

23. A Room and a Half (2009). Dir. by Andrey Khrzhanovsky.

When intentions are noble and talent is pure, a film can be interesting even if it’s not altogether coherent. This 2009 highly subjective, at times opaque, and very poetic film was made by a director who was making fascinating cinema since mid-60’s. Khrzhanovsky is known and revered in the animation world as one of the most original artists.

Here he tackles the eternal Russian themes of history and Motherland, by telling the story of the great poet Joseph Brodsky’s imaginary return to St. Petersburg. By itself, it’s poetic license-since his 1972 banishment from USSR, Brodsky never again saw his homeland.

The basis of the film is Brodsky’s own materials-diary entries, drawings, and, especially, prose (little-known to general reader, as Brodsky’s fame is in poetry). The idea came to Khrzhanovsky in early 2000’s, and first he made an animated short “A Cat-and-a-Half”, bringing Brodsky’s drawings to life and mixing them with his family photographs.

In this film, that “artificial documentary” technique is combined with the flimsy plot-Brodsky journeys back on a Trans-Atlantic liner, reminiscing along the way.

Visually, it’s very interesting-the documentary footage is seamlessly blended with the fiction, and the animated interludes are predictably zany and creative. However, the film never settles on what it wants to be-a biopic, a visual poem, a documentary? Nonetheless, leaves a satisfying aftertaste.

22. Kotch (1971). Dir. by Jack Lemmon.

A quality film, done in, as many on this list are, by low rate of profit. Jack Lemmon is widely known and adored for his impeccable timing as an actor, particularly in comedies. Here, he brings that gift to directing, making a poignant, humane, and competently made drama. In fact, it’s potentially the best family drama West of Yasujiro Ozu.

Lemmon deftly guides his friend and frequent co-star Walter Matthau in a role of Joseph Kotcher, an aging man who is being shipped off to a retirement home by his uncaring family, but finds courage to break the bonds, experience more of life, and find a new quasi-family in the person of a pregnant teenager (Deborah Winters, another solid turn).

Lemmon has shown that working with the likes of Billy Wilder has really rubbed off on him-the timing, particularly in the comic moments, is close to impeccable. He also demonstrated a good control of other elements-in addition to Matthau, the film received Academy Award nominations for Best Editing, Best Song, and Best Sound (it won none).

That’s a clear indication that Lemmon, at the very least, knew how to let his collaborators create unhindered and then how to combine their efforts into a coherent whole. He would go on to further acting acclaims, and more collaborations with Walter Matthau, but “Kotch”, sadly, remains his sole directing credit.

21. Mystery Men (1999). Dir. by Kinka Usher.

The cast least alone should make one at least curious-Tom Waits, Ben Stiller, Hank Azaria, Eddie Izzard, Geoffrey Rush, Janeane Garofalo, William H. Macy, Lena Olin, Paul Reubens. Kinka Usher, a French-born director and cameraman of many award-winning commercials, gets all the necessary laughs out of this quirky cast.

This movie, admittedly, will not open up new intellectual paradigms for you-but it’s mostly hilarious. It’s hard to believe these days, with a comic-based movie coming out at the rate of two per season, but back in the late 90’s the superhero movies were made much less frequently, and were usually a big deal. This one spoofs them all with assured verve.

Featured here are Stiller’s Mr. Furious (power: he gets mad easily), Garofalo’s The Bowler (she bowls well), Macy’s The Shoveler (he can shovel really fast), and other assorted “superheroes”, who have to step up to the plate when the pompous actual superhero Captain Amazing (Greg Kinnear) is captured by the evildoers.

The Mystery Men are aided by Tom Waits’s mad doctor, who is good at making non-lethal weapons and, being a bit of a gerontophile, frequents tea parties at retirement homes. Making fun of such 90’s turkeys as “The Phantom” and Schumacher’s Batmans (particularly the dreary second), Usher used the garish aesthetic of the comic source to mock strained gravitas and dead seriousness of a genre that should also be fun.

Sadly, it got mostly panned by the critic and shunned by the industry. The criticism was along the same lines as it was for Warren Beatty’s “Dick Tracy”, and it was equally annoying-few things are as killjoy as overtly high-brow critics turning up noses and telling audiences what to enjoy. Admittedly, there are flaws-at 2 hours, it’s exactly 30 minutes too long. But for the fun Usher provided, he really deserves better.

20. A Place on Earth (2001). Dir. by Artur Aristakisyan.

Aristakisyan, an Armenian from Moldova, is still alive and well (as well as any dissenter can be in the modern-day Moscow), and, at 55, not that old. But it’s unlikely that he’ll make another feature any time soon.

Born and raised in Chisinau, and a VGIK graduate (where he now heads the “School of Parables” workshop), Aristakisyan is a life-long and committed hippie, and by his own admission he got into filmmaking to share the genuine hippie philosophy and worldview with the world.

So far, his entire oeuvre consists of this feature and a feature-length documentary Palms (which is arguably even better). Both films were made over a span of several years, and outside of the Russian moviemaking system.

Both would make great companion watching pieces with works like Woodstock, Hair, or Zabriskie Point. Being a true hippie in the urban wastelands of Moldova or Russia is a decidedly different experience than sporting beads and other shallow attributes while comfortably living off either slinging hash or parents’ credit cards.

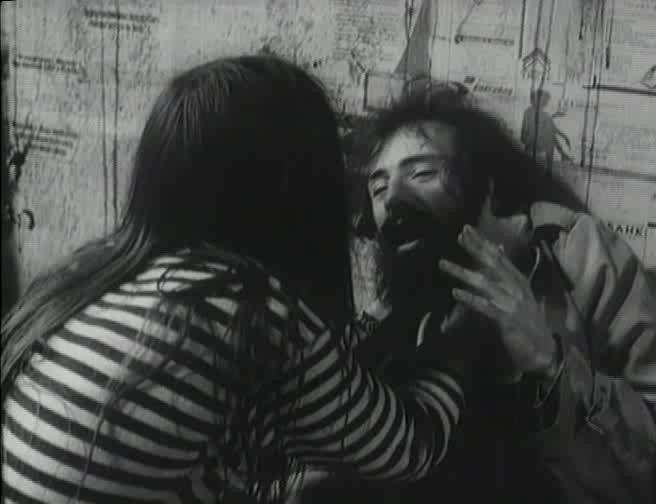

Aristakisyan’s hippies have more in common with hobos and winos. Even though this black and white film is visually stunning, it’s far from being pretty. Aristakisyan is not afraid to show warts (or rotting warts), and his heroes eat stuff that would make a vulture hurl. In this film, he shows how a noble and generous creed becomes moot and dies off due to disciples being unable or unwilling to live it.

The camera is trained on the actual abandoned building where the societal outcasts dwell. An honest artists to the core, Aristakisyan only uses natural lighting, giving the film a strange and beautiful aura. Let’s hope he survives Putin’s Russia to give us some more lyrical honesty.

19. Wristcutters: A Love Story (2007). Dir. by Goran Dukic.

Suicide-based comedies are never an easy sell. Croatian-born and raised Goran Dukic has, so far, gone the way of two other Balkan greats, Dusan Makavejev and Emir Kusturica, at least as making features in the West is concerned.

Virtually unnoticed on official release, this black comedy enjoyed a successful festival circuit run, tepid DVD sales, and then somewhat of a cult following. It’s definitely not perfect, but there is much to be enjoyed.

Most of it take place in a sort of hell for those who have committed suicide. The protagonist, who kills self over love, soon discovers that this “hell” is really not much different than his Earthly life-just a lot drabber. Mostly, just a maze of run-down buildings and lame “neighborhood” bars with poorly functioning jukeboxes.

When he learns that his girlfriend, over whom he took his life, has also committed suicide, him and his new Russian friend go on a journey to nowhere, trying to find her, picking up a mysterious girl who feels she is wrongly placed here along the way.

The minuses include indie aesthetics, a story that meanders a bit, and a weak central performance from the main protagonist. Dukic appears to have repeated the mistakes Emir Kusturica and Wong Kar-wai made with “Arizona Dream” and “My Blueberry Nights”, respectively-his “American” heroes walk, talk, and act like Yugoslavs. But there are many pluses.

The dingy afterlife is masterfully recreated on a low budget, added by the ingenuity of description. Boardwalk Empire’s Shea Whigham excels as a Eugene Hutz-like Russian, and the beautiful and perennially underused Shannyn Sossamon rises well to the challenge.

In all, the supporting actors carry the film with their quirkiness, the most memorable of them being the inimitable Tom Waits as The Kneller. Soundtrack deserves a particularly high rating, it’s amazingly eclectic and yet perfectly fitting, mixing Gram Parsons country, Artie Shaw’s jazz, quality punk numbers, the swirling accordions of Gogol Bordello, and great incidental music. And, of course, you can’t have a bar full of suicide victims without Joy Division playing.

The imagery and music combine to make this a surprisingly life-affirming experience. Dukic has been rumored for years to be working on his second feature, here’s wishing he gets out of cinema’s development hell soon.

18. Phase IV (1974). Dir. by Saul Bass.

Saul Bass is and Academy Award-winning director (with two more nominations), as well as an influential and internationally known designer. Yet this smart sci-fi thriller remains his sole feature outing (his win is Best Documentary Short, nominations-Best Live Action Short).

For decades, he created some of the most memorable title sequences in cinema, from A Man with the Golden Arm to Casino, and his style is being frequently imitated and paid homage to. However, the ingenuity and creativity present in his shorts and design works ended up being stretched a bit in feature form.

That’s not a panning of the film-Phase IV is definitely one of the most intelligent and intriguing sci-fi films ever made. It just seems too smart many a time for its own good. It particularly applies to the two male leads, whose dialogue is often of the sort that’s normally heard in Planet Earth and other nature documentaries.

Best and most human acting comes from Lynne Frederick as the female lead, and the experimental electronic soundtrack may be a bit too 70’s. Main criticism of the film is that it’s designed rather than directed, which is partially true. And yet Bass created a haunting, visually stunning film that never disappoints.

Some critics have unfairly compared it to monster insect B-movies of the 50’s-nothing is further from truth. The advanced ants, in this case, are normal sized-they just developed superior abilities, potentially succeeding humans as the dominant species on Earth.

Bass’s collaborator, famed nature photographer Ken Middleham, provided some fascinating sequences of ant life, making the insects protagonists in their own right. Perhaps it’s this refusal to chew thigs down for the audiences, this commitment to asking questions rather than providing easy answers, that unnerved the producers, preventing the film from getting proper distribution. Cut, too, was the mesmerizing final montage sequence, where Bass imagines how the world of the future looks.

Despite the obstacles, the film soon achieved cult status, and is one of the more influential sci-fi films, propelled by Bass’s inspired vision (of note-it was the first film to feature crop circles, several years before they became the craze).

17. Espoir: Sierra de Teruel (1939, rel. 1945). Dir. by Andre Malraux (and Boris Peskine).

A Hemingway-like story set during the Spanish Civil War that, arguably, surpasses the actual Hemingway film adaptations. Small wonder-Andre Malraux was a writer on par with Ernest, one of the most influential French novelists of the XXth century.

Aided by the Russian-born documentarian Boris Peskine (for whom this film is also a sole feature directing credit), Malraux has successfully adapted his own novel set in Spain, based on his account and experience fighting for the Republican side.

Though a work of fiction, it has a strong documentary and verite feel to it, only slightly being guilty of romanticizing the Republican cause (the real situation in Spain was much more ambivalent than pro-Republican writers would have you believe). And then the film was almost wiped out from existence. World Wars happen.

It was shown twice in 1939, then pulled at the protest of the Spanish Nationalist ambassador, and most copies were destroyed during the German occupation of France (as was Malraux’s last novel and nearly the man himself). Fortunately, one copy miraculously survived, and the film received its proper premiere in 1945.

Even though Malraux had to finish the shooting in the Paris studio, after the fall of the Spanish Republic, the honest depiction of the war is inspiring and remarkable, with several scenes standing out for their dramatic punch (especially the climax, of the villagers carrying the dead down the side of the mountain).

Malraux would go on to be a hugely influential writer on arts, and the first French Minister of Cultural Affairs, but this film remains as his sole foray into filmmaking.